Graham Allison, an American professor of government at Harvard University and prominent political adviser, is credited with formulating the concept of the “Thucydides’ trap” with respect to the rise of China and the supposed threat that it poses to the hegemonic United States. The ancient Greek historian, Thucydides, proposed that the rise of Athens as a political power instilled in Sparta (then the existing dominant state) the fear of a rising power which would make war inevitable. On the basis of his historical comparative study, Allison concluded that out of sixteen cases of rising powers challenging a ruling power, war has occurred in twelve of them.

How rising states can fit into the current world system of states depends on how one conceptualises the existing world order. If the international system is one of competitive anarchy with a number of relatively equal competing states, a challenge by a rising state to a dominant one might lead to war. But only in circumstances in which the dominant country’s place in the international order is significantly undermined; and only if the dominant country has a realistic possibility of winning, will it rationally defend its status by declaring war. It is very doubtful if either of these conditions currently applies to the USA. The current economic system is one in which the USA retains a political/cultural and economic hegemony and the rising power, China, sustains its competitive interdependence.

Rising Powers

A ‘rising power’ is defined by a cumulative growth in its gross domestic product exceeding that of an established major power. This is only one measure of its power and others (ideology, technology, weaponry) are also important. However, it is a crucial one and a good indicator or ‘rising’ and ‘declining’ powers. One example of a peaceful transition is that of the United Kingdom. In 1820, the UK had a GDP of 36,200 million international dollars; Germany 26,800 and the USA only 12,500. By 1872, with a GDP of 107,000 million, the USA was already ahead of the UK’s 105,800 [1].

The British Empire however did not enter into war with the USA which facilitated a gradual transition from a major to a hegemonic power after the Second World War. Britain remained a leading, even a ‘great’ power, in the early twentieth century. It was not directly threatened by the USA; trade, politics and culture remained cooperatively interdependent. By 1970, the USA had emerged as a super power with a GDP (3,081,000 million international dollars) greatly in excess of Germany (843,410) and the UK (599,016).

In the post World War II period, the reaction of the European states to the hegemony of the USA and the challenge presented by the communist states under the leadership of the USSR was to form a regional bloc in the form of the European Union. In the bi-polar world system, the dominant powers (USA and USSR) formed a competitive but relatively stable political hierarchy, policed through nuclear weapons. The European states could maintain their political, economic and cultural power by fending off supposed threats through military alliances (NATO) as well as overt and covert measures against the communist powers.

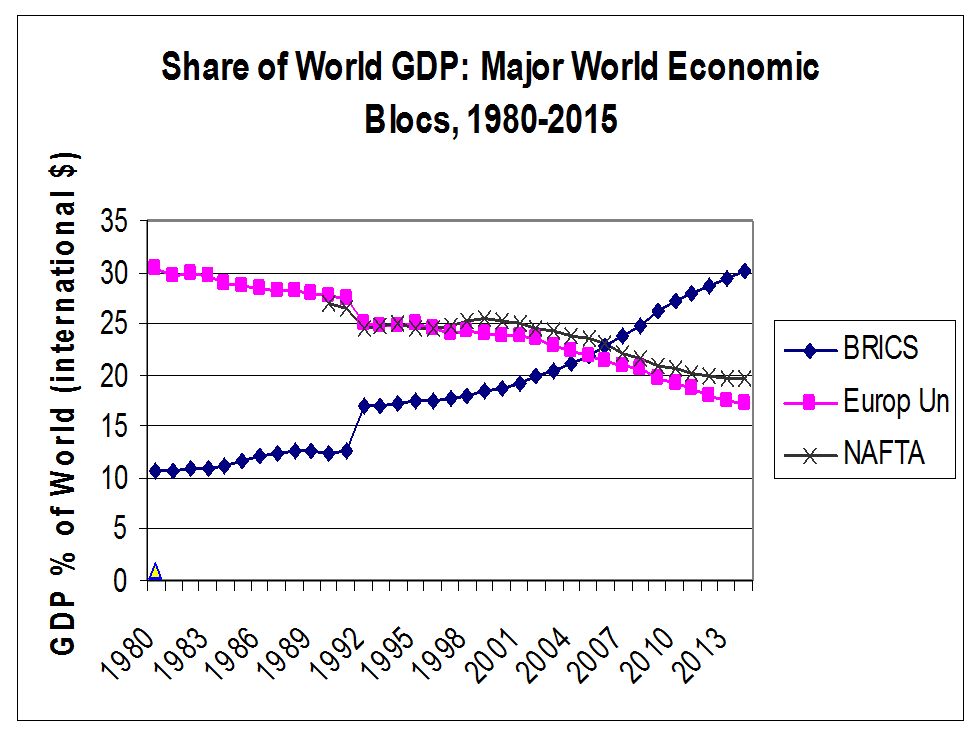

This Union immensely strengthened the European states in the post-World War II period. But it proved ineffective as an economic and political challenge to the USA. Despite its continual enlargement, the European Union suffered cumulative relative economic decline whilst maintaining a leading position in the international system. The formation of the European Union and North American Free Trade Area (USA, Canada and Mexico) did not deter the rise of China, and both Western blocs fell behind the BRICS, as indicated by Figure 1.

Figure 1. Proportion of world GDP 1980-2015: BRICS, European Union, Eurasian Economic Union and NAFTA.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base, 2015. Purchasing power parity (Current international dollars).

From producing only 11 per cent of world GDP in 1980, the BRICS equalled the share of the EU in 2007 and by 2015, the BRICS accounted for 30 per cent of global GDP – over 10 per cent greater than NAFTA.

China, the dominant economic player in the BRICS, in a relatively short period of time has outstripped the USA not only in total gross national product. As Allison points out, by 2015 it had surpassed the USA in the amount of its exports, savings, energy consumption, steel production, motor car market, E-commerce market, internet use, and holder of foreign reserves.

A Peaceful Power Transition?

How then do these developments impact on the China-USA strategic encounter? Xi Jinping has been very cautious in framing China’s rise. He has emphasised the peaceful intentions of China. In his speech in Seattle on 24 September 2015, he emphasised the importance of mutual understanding, and called for a deepening of ‘mutual understanding with the US’, we ‘want to see more understanding and trust, less estrangement and suspicion, in order to forestall misunderstanding and miscalculation’.

Unlike the communist powers, neither China nor the Russian Federation presents an ideological ‘threat’ to the USA: both seek a competitive market economy set within the parameters of the IMF and WTO trade order. Remember: Xi Jinping at Davos in January 2017 strongly endorsed globalisation. In his Seattle speech, he has referred explicitly to the ‘Thucydides trap’. ‘There is no such thing as the so-called Thucydides trap in the world. But should major countries time and again make the mistakes of strategic miscalculation, they might create such traps for themselves’. It is here that China is responding to a potential ‘threat’ by the USA.

Thucydides pointed out that both Athens and Sparta formed alliances with other states to counterbalance the power of their supposed adversary. China has formed alliances with the formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a wider linkage of countries constituting the BRICS and the One Belt One Road initiative. Cooperation between Russia and China is prompted by the increase in economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU and the attempt to reassess trade relations between the USA and China by President Trump.

Both countries have a symmetry for mutual trade – already indicated by Russia’s energy deals with China. The two countries have carried out joint military manoeuvres in the Baltic and the China Seas and the Sea of Japan. Wei Fenghe, China’s defence Minister at a meeting in Moscow in April 2018 is reported to have said: ‘The Chinese side has come to show Americans the close ties between the armed forces of China and Russia.’ These statements fire media commentators, such as Hal Brands, to define the ‘New Threat to the US: the Axis of Autocracy’ (Bloomburg, 19 April 2018).

The Military Balance

None of these associations involves military cooperation. As noted in my previous Valdai paper [3 July 2018], the USA is supreme as a military power. The logic of deterrence would bring China to seek military partners among other friendly states. Here an obvious alliance would be with Russia. Such an alliance would not change very much the ratio of military expenditure. For 2017, the share of world expenditure on armaments would be 38.2 per cent for the USA, for the China/Russia alliance only 13.4 per cent.

But if we combine Russia’s and China’s military assets, there is a greater equivalence in the armed forces to the military power of the USA. The joint forces are shown in Table 1. Russia and China combined gives the alliance a 9:10 ratio for tactical aircraft, double the number of bombers; of great importance is the near equality in ICBM launchers; though there remains a significant negative imbalance in helicopters. Naval power, except for aircraft carriers, gives the alliance an advantage, notably Russia (49) and China (57) combined have double the number of attack missile submarines. In land forces, the alliance is greatly superior in all areas – active military personnel, tanks and artillery. In any rational scenario, the destructive consequences of military confrontation greatly outweigh any possible gains to both sides.

Table 1. Military Hardware 2017; USA, China and Russia Combined

| AIR POWER (UNITS) | USA | Russia China Combined | ||

| Tactical aircraft | 3424 |

3098 |

||

| Bombers | 157 |

301 |

||

| Heavy/medium helicopters | 2645 |

758 |

||

| ICBM lauchers |

400 |

383 | ||

|

SEA POWER |

||||

| Cruisers, destroyers, frigates | 96 |

115 |

||

| Aircraft carriers | 11 |

2 |

||

| Attack Nuclear submarines | 54 |

106 |

||

|

LAND FORCES |

||||

| Active personnel (millions) | 1.348 |

2.935 |

||

| Battle Tanks: | 2831 |

9830 |

||

| Artillery | 6894 |

18713 |

||

The Military Balance 2018. [Printed online by Routledge]

The time for the USA to crush China as a rising power has gone. The USA is still a hegemonic power, though weakened by its excessive military spending and world ambitions. It took over a hundred years for the USA to realise its political and economic power as a world hegemon. The current challenge of China presages a power transition: a shift of political and economic influence to the east. A natural geographical counterpoint to the USA would involve a region covering the central Asian states and the Russian Federation. One lesson from Thucydides is that the alliances formed by Sparta and Athens led to destructive wars for both sides. Alliances may drag great powers into costly unwanted wars. An optimist would believe that the threat of nuclear destruction provides a rational course to maintain peace.

David Lane is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences (UK) and Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University. His recent work includes: Changing Regional Alliances for China and the West (with Guichang Zhu), 2018. The Eurasian Project in Global Perspective, 2018.Please read another article by David Lane "Power Transition and the Rise of China"

[1] All data taken from the Maddison Project Database, version 2018.