The rise of China and the relative decline of the USA raises the problem of power transition; that is, the way in which a rising state challenges and displaces a dominant state or set of states. The view of many commentators is that China’s claims for political and geopolitical recognition, its enormous economic growth and rising military power, promote insecurity on the part of the great powers, particularly the USA. Some even believe that to maintain its hegemony, the USA should be prepared to declare war.

Current discussion is predicated on the ‘threat’ posed by China. The power of a country in international affairs may be estimated by a number of criteria: its military capacity which in turn is derived in great part from its economic strength, its human and social capital – the size and educational level of its population, and finally, its moral and ideological values, giving rise to its ‘soft power’. Here only the first two aspects are discussed.

From Dependence to Sustainable Competitive Interdependence

Following the ‘opening up’ in 1979, China moved from a phase of peripheral dependence to one of sustainable competitive interdependence. In the first phase China pursued economic reform. Under the hegemony of the Communist Party of China, marketisation and limited privatisation underpinned moves to the world market. Initially, China experienced a period of peripheral dependence on the Western core states while it developed its export industries mainly based on labour intensive manufacture.

It was widely believed that China would decline consequent on competition with leading Western economic powers and would become a peripheral materials’ supplier of low value products – an appendance of Western high tech production and services.

GATT/WTO policies successfully opened up world trade from which China greatly benefitted and became a ‘rising power’ dependent on the core states for investment and markets.

An unexpected consequence of the opening up of markets was that globalisation led to success in the global market. The enhanced mobility of capital under conditions of free trade promoted development. China moved from being a state of peripheral dependence to one of sustainable competitive interdependence. Not only did China become a major supplier of manufactured goods on the world market, but it successfully competed in the high labour cost Western industrial countries while sustaining a state led economy. Interdependence strengthened China and led to a decline in the relative economic power of countries at the core of world capitalism. In return for cheap imports they suffered de-industrialisation and associated impoverishment of the labour force.

The Changing Balance of Economic Production

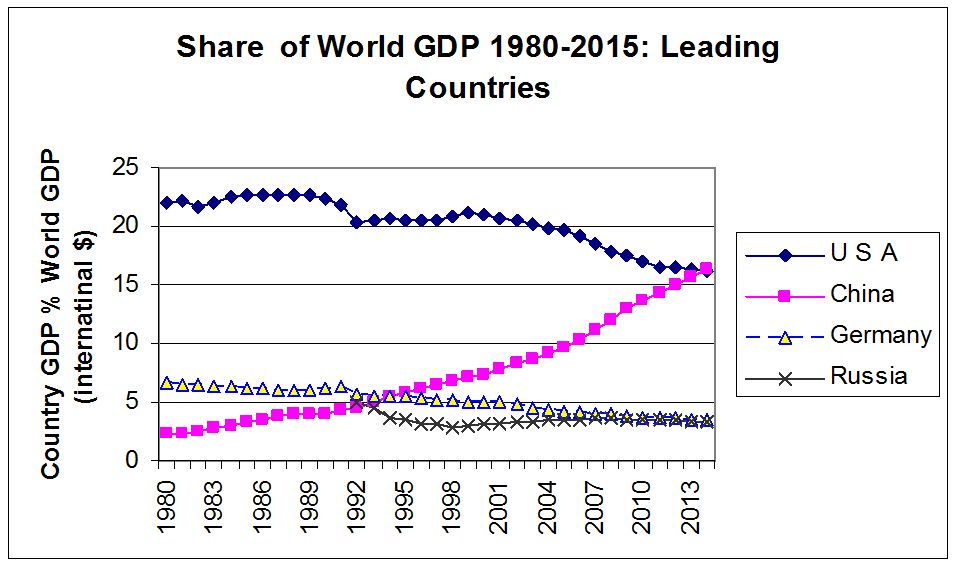

China’s exceptional rise may be measured by the decline in the world share of gross domestic product (GDP) for the Western core states illustrated in Figure 1. China’s share of world GDP rose from some three per cent in 1980 to 17 per cent in 2015. In terms of national GDP China caught up with the USA in 2015. (Statistics used in China, use a different measure of GDP which puts China in second place, even in 2018). Figure 1 shows the comparative decline, not only of the USA but of the leading European states (Germany and Russia).

Figure 1. Proportion of World GDP 1980-2015: USA, China, Germany and Russia

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base, 2015.

While the graph shows the gross national income of countries, the picture changes somewhat when we consider per capita income where China is well behind Western countries. In 2015, the gross national income per capita measured by purchasing power parity in dollars, came to 13,345 for China, 23,286 for Russia and 53,245 for the USA (the highest was Norway with 67,614 international dollars per head). A more comprehensive measure of well-being devised by the United Nations Human Development Index (including life expectancy, years of schooling and income) put China in 2016 in 90th place in the world order, well below Russia (49th) and the USA (10th). (Data derived from human Development Report 2017).

These data lead to two different positions. First: those who emphasise the displacement of the Western states by China (and other rising powers, such as India). Second: commentators who stress the very large gap between the economy of China and the West as well as significant developmental differences. While the first group considers the dynamic of the changes in relationships, the second emphasises the considerable difference in real conditions between the USA and China. All commentators however recognise that there has been economic advance and a significant narrowing of the gap between China and the leading Western powers. China presents a challenge. But does this pose a power transition which might lead to war?

The Military Balance

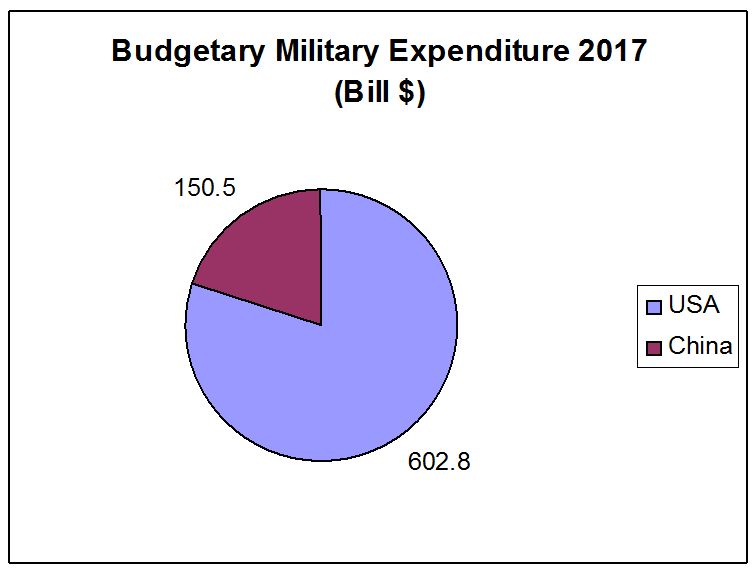

Intelligence on the military strength of any country is shrouded in secrecy. However, scholars can make comparative estimates from published data – and such sources are the basis on which friendly and hostile states make their policies. The London Institute for Strategic Studies’ estimates of the military expenditure is shown in Figure 2 for the USA, and China.

Figure 2 Military Expenditure 2017: USA and China

Source: The Military Balance 2018: Defence budget (billion $). Routledge Online.

The chart illustrates an overwhelmingly greater military expenditure by the USA and its allies compared to China. In monetary terms, the USA spends four times as much as China. Put another way, the USA accounts for 38.2 per cent of world military expenditure, compared to China’s 9.2 per cent. This puts into perspective the increase in Chinese expenditure (24.8 per cent) in 2016-17.

Military Hardware

This spending is reflected in the military hardware available to both sides. The USA has significant military superiority, but not in everything. Table 1 shows the relative strength of the USA for different classes of armaments. While one can speculate on the quality of the armaments and military leadership, these data provide a good benchmark. The USA has overwhelming superiority in air power: it has nearly six times as many intercontinental ballistic missiles, one and a half times as many tactical aircraft, though fewer bombers. The picture regarding sea power is somewhat mixed: there is almost equality in warships, but a severe imbalance in aircraft carriers where the USA has over 11 times as many as China. These are offensive platforms and further enhance the air supremacy of the USA. It is in land power where China is strong having over two million regular troops, compared to the USA’s 1.348 million; China also has 6740 tanks – more than double the number of the USA. Defensively, China has over 13,000 pieces of artillery defence – double the number of the USA.

Table 1. Military Hardware 2017; USA, China

AIR POWER

|

|

USA |

China |

|

Tactical aircraft |

3424 |

1986 |

|

Bombers |

157 |

162 |

|

Heavy/medium helicopters |

2645 |

383 |

|

ICBM launchers |

400 |

70 |

|

Air Power (Total units) |

6626 |

2601 |

SEA POWER

|

Cruisers, destroyers, frigates |

96 |

82 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

11 |

1 |

LAND FORCES

|

Active personnel (millions) |

1,348 |

2,035 |

|

Battle Tanks |

2831 |

6740 |

|

Artillery |

6894 |

13420 |

The Military Balance 2018. Printed online by Routledge.

Growing Tensions

Against a background of relative Western economic decline, China is confronted in different ways by assertive policies emanating from the USA. The USA has responded to China with its ‘pivot to Asia’ then its ‘rebalance Asia’ policy. China has faced growing challenges to its security and a trade war is threatened. It is confronted by massive US military forces stationed in the Pacific. Japan also regards China as a threat to its position as a Pacific leader. These commercial conflicts are exacerbated by historically based disputes with Japan, South Korea and Taiwan as well as the Philippines. The formation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), signed in February 2016, excluded China. China will face higher duties on exports. While the USA has supremacy in many forms of military hardware, China presents a significant military foe. However, China’s strength in land forces and tanks is less relevant to current warfare, and the USA is clearly dominant in the air. Whether these changes in the relative strengths of the West and rising powers lead to a power transition by peaceful means or a war to sustain the hegemony of the West will be the subject of my next contribution.

David Lane is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences (UK) and Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University. His recent work includes: Changing Regional Alliances for China and the West (with Guichang Zhu), 2018. The Eurasian Project in Global Perspective, 2018.