Economic Statecraft

Building a Resistance Economy – Lessons from Chile's Invisible blockade

© Reuters

What role will Russia play in tomorrow's world order? The answer is: it depends on Russia's reaction to today's total economic warfare. Because this large-scale multisectoral warfare, ranging from energy to finance, has inadvertently turned Russia into the laboratory of a first-of-a-kind experiment. Tomorrow's economists, scholars and policy-makers will study carefully Russia's response to the West-staged economic warfare with the goal of understanding how to build sanctions-proof national economies. And Russia itself needs to draw on the past if it does want to pass the stress test, as the past offers a lot of examples of economic wars, like the Nixon's assault on Allende's Chile.

The US-led total economic warfare on Russia has never had as its supreme goal the collapse of the Russian economy. The US is well-aware of the fact that a country like Russia – a major producer-and-exporter of energy, food products, weapons and other goods – cannot be ousted from the global market. The dream of Russia as a bigger North Korea is and will remain just a dream, the wishful thinking of the most radical neocons and liberal-progressives.

The US-led total economic warfare on Russia has never had as its supreme goal the collapse of the Russian economy. The US is well-aware of the fact that a country like Russia – a major producer-and-exporter of energy, food products, weapons and other goods – cannot be ousted from the global market. The dream of Russia as a bigger North Korea is and will remain just a dream, the wishful thinking of the most radical neocons and liberal-progressives.

Conversely, the EU-Russian decoupling was and isn't just a dream: it's been being a primary goal of the American foreign policy since the Obama era – the era when it all began: Dieselgate, the killing of the South Stream, Euromaidan, the first anti-Russian sanctions-regime.

Sanctions are a way to break up the natural-born EU-Russian partnership, more in particular the Mackinderian nightmare of the Russo-German axis. Sanctions are a way to expel Russia from the opportunity-rich EU market, with greater US exposure as a result. Sanctions are a way to expel Russia to Asia with the expectation that it will drown in its near abroad's problems: tribalism, ethnic conflicts, religious wars, terrorism, exhausting competition with other powers. Sanctions are a way to slow down the EU path towards emancipation, which inevitably goes through a deeper relation with Russia – as Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel stated repeatedly in recent years. Indeed, when the West sanctions Russia, it's primarily the EU that sanctions – and that it is hit by Russian reprisals. As the saying goes: two dogs strive for a bone, and the third runs away with it.

The total economic warfare which broke out in the wake of the Ukraine war is unprecedented in scale. More than 1,000 corporations exited, or suspended operations in, the Russian market in the first four months of conflict, against the background of destabilizing financial actions – like the restrictions on Russia's participation in the SWIFT – and sanctions targeting trade and high technology, including chips. The ensemble of separate penalties – more than 6,000 as of May 2022 – turned Russia into the world's most sanctioned country. The expectation is to inhibit Russia's growth and development in the long-term by depriving it of revenues and know-how, with Ukraine playing a fundamental role in this scheme: the battlefield of an attrition warfare combining elements and aims of the Soviet-era Afghan insurgency and of the Iran-Iraq war.

What the Western policy makers did not know, or perhaps they did know but they underestimated, is that many things changed between 2014 and 2022. In fact, Russia has managed to build a stress-resistant economy over the years, with the result that sanctions are likely to speed up the already underway processes of import substitution, financial waterproofing and economic diversification, if the government reactes with foresight.

From the British response to Napoleon's Continental Blockade we've learnt that even developing and seemingly encircled countries can circumvent enormous sanctions-regimes with a proper mix of shrewdness and forethought. Now, from the first hybrid warfare ever – the US vs. Salvador Allende's Chile –, we're going to understand how a “total covert warfare” looks like and what can be done to fight it properly.

Allende's Chile and the world-first hybrid warfare

The US-backed multi-level unconventional warfare against Allende's Chile is undoubtedly one of the most tragic, and yet successful, experiments of manmade destabilization in global history. Chile was traditionally known as Latin America's most stable country, with only two short-lived authoritarian periods during the 20th century, and was led by a peace-ensuring and give-and-take political system based on multi-party coalitions until 1963. But that enviable status changed (forever) in the wake of the Cuban revolution – the US feared that a domino-effect was about to take place in the rest of the continent, and Allende's historical election prompted the Nixon administration to design and implement a boundless warfare destined to teach posterity the deadly potential of economic and financial wars.

It's more than important to study Nixon's war on Allende's Chile because mainstream historiography never paid adequate attention to its economic component. Terrible mistake. The Chilean army got to overthrow the government, backed by large part of the population, also because Henry Kissinger fulfilled Nixon's peremptory order: he made the Chilean economy scream.

The total economic warfare which broke out in the wake of the Ukraine war is unprecedented in scale. More than 1,000 corporations exited, or suspended operations in, the Russian market in the first four months of conflict, against the background of destabilizing financial actions – like the restrictions on Russia's participation in the SWIFT – and sanctions targeting trade and high technology, including chips. The ensemble of separate penalties – more than 6,000 as of May 2022 – turned Russia into the world's most sanctioned country. The expectation is to inhibit Russia's growth and development in the long-term by depriving it of revenues and know-how, with Ukraine playing a fundamental role in this scheme: the battlefield of an attrition warfare combining elements and aims of the Soviet-era Afghan insurgency and of the Iran-Iraq war.

What the Western policy makers did not know, or perhaps they did know but they underestimated, is that many things changed between 2014 and 2022. In fact, Russia has managed to build a stress-resistant economy over the years, with the result that sanctions are likely to speed up the already underway processes of import substitution, financial waterproofing and economic diversification, if the government reactes with foresight.

From the British response to Napoleon's Continental Blockade we've learnt that even developing and seemingly encircled countries can circumvent enormous sanctions-regimes with a proper mix of shrewdness and forethought. Now, from the first hybrid warfare ever – the US vs. Salvador Allende's Chile –, we're going to understand how a “total covert warfare” looks like and what can be done to fight it properly.

Allende's Chile and the world-first hybrid warfare

The US-backed multi-level unconventional warfare against Allende's Chile is undoubtedly one of the most tragic, and yet successful, experiments of manmade destabilization in global history. Chile was traditionally known as Latin America's most stable country, with only two short-lived authoritarian periods during the 20th century, and was led by a peace-ensuring and give-and-take political system based on multi-party coalitions until 1963. But that enviable status changed (forever) in the wake of the Cuban revolution – the US feared that a domino-effect was about to take place in the rest of the continent, and Allende's historical election prompted the Nixon administration to design and implement a boundless warfare destined to teach posterity the deadly potential of economic and financial wars.

It's more than important to study Nixon's war on Allende's Chile because mainstream historiography never paid adequate attention to its economic component. Terrible mistake. The Chilean army got to overthrow the government, backed by large part of the population, also because Henry Kissinger fulfilled Nixon's peremptory order: he made the Chilean economy scream.

In the event that the acute phase of the conflict in Ukraine really turns out to be very long, which, apparently, is the case, then the elementary needs of survival will force Russia to get rid of what binds it to Europe, Valdai Club Programme Director Timofei Bordachev.

Opinions

In order to understand how the US managed to drag Chile into a civil war-like situation in only three years it is necessary to explain what was the country's landscape on the eve of Nixon's covert war. Chile in the 1960s was South America's best-performing economy, yet it had one of South America's most polarised societies: 7 out of 10 lived with about or less $220 per year, with 1 out of 10 having more than $6,000 annually. Moreover, the job market was characterized by deep wage differences, cross-sectoral rivalries and high rate of underproductivity – about one-third of the total workforce was employed in low-productivity activities. The situation was further worsened by the outbreak of stagflation crises on a regular basis and, last but not least, by the heavy reliance on foreign exports and foreign investments.

Since the colonial times, mineral exports had played a primary role in giving rise to temporary economic booms. But they never benefited the economy as a whole since no government reinvested the revenues in import substitution, industrialisation and wealth redistribution. In 1970, copper exports accounted for 76.9% of all total exports – an awful lack of diversification that the US would easily exploit. Furthermore, the copper industry was almost entirely owned by American companies which, in addition to paying low taxes, invested more in automation than in workforce – as shown by the fact that the number of copper miners declined by 16% between 1931 and 1959. And to make matters worse, Chile was tied to the US by an unfair deal, repealed only in 1967, according to which 80% of total copper production had to be sold to the US at a US-set price. Last but not least, American firms never shared know-how and never invested in upskilling – something that caused many troubles at the outbreak of Nixon's war.

Then there was the fifth columns question. The national economy was ruled by a Western-backed small élite, whose members were in business with the West and had sold ownership of many industries to foreign buyers. Numbers speak loud: US firms handled 85% of total mineral exports, Western-controlled companies hegemonised 50% of wholesale trade, 61 of the 100 largest companies operating in the national market were foreign-owned, of the $1,672 million FDI inflows in the period 1954-1970, $1,457 were from the US, and most of foreign debt was in the hands of the US.

US firms had always been present in the Chilean market, but their dynamism recorded a surge in the post-Cuban revolution – as if they wanted to prevent a revolution from taking place by colonizing the country economically and by establishing an iron pact with the most powerful segments of society. Concurrently with the economic colonisation that took place in the 1960s, the ruling class' lack of foresight made Chile an import-dependent country in crucial sectors like equipment, machinery, spare parts and fuels – with 90% of the annual national demand met from abroad.

Returning to the fifth column question, it's essential to name the Edwards dynasty, the country-richest family-empire. The Edwards played – and still play – a dominant role in the national economy, being owners – during the Allende era – of one commercial bank, two publishing houses, five insurance companies, seven financial and investment corporations, with holdings in 13 industries. In particular, the Edwards played a critical role in mass communication, being owners of El Mercurio – the country's largest-selling daily newspaper chain. It was more than a media empire, it was an unmatched monopoly through which they controlled almost 100% of Chilean media and publishing industries. As we're going to see, such an empire was successfully weaponised during the Allende era with the goals of spreading antigovernment propaganda, fostering social polarization and pumping up far-right political views.

The agribusiness, similarly to mass media industry, was hegemonised by a bunch of Western-linked families who held close to 99% of all arable lands and who enjoyed state subsidies, loans and friendly profit taxes. Numbers show why their dominance was economically harmful: smallholders owned a bit more than 1% of all arable lands, but they produced close to 4% of national output and employed 13% of all agricultural workforce. A timebomb ready to explode.

When it all began

1960s. The Castrist revolution has just ended and the US wants to avoid a "Second Cuba". It's Chile that the US believes to be the most vulnerable to USSR-driven destabilizing attempts. In order to prevent the Communist from rising to power, and later to dethrone Allende, the US starts a years-long subversive campaign. The first hybrid warfare ever.

To begin with, it is essential to understand how Allende eventually came to power. Therefore not 1970, but 1961, will be the beginning of this (long) story. Indeed, the anti-Allende campaign started in 1961, that is three years before the 1964 elections, hopefully to avoid the victory of the ever-growing left-wing front. To this end, the US infiltrated a number of entities, from peasants organisations to labor unions, and political parties, from Christian Democrats to Radicals. When the election year finally arrived, it would be renamed the "terror campaign" due to the unprecedented level of widespread political violence and social chaos. It was the third time that Allende, the Socialist Party's leader, run for elections. But that time something had changed: his party had grown, his popularity had increased internationally, he had become the major challenger of the Christian Democrats' candidate: Eduardo Frei Montalva. That's the reason of the so-called terror campaign: extensive resort to psyops, entryism and disinformation so as to spread the Red Fear among public opinion and to make the unpopular Frei Montalva popular.

Tens of thousands of posters were posted on the urban walls and hundreds of thousands of leaflets were distributed to ordinary people, in both cases depicting the Soviet invasion of Santiago or Cuban soldiers killing Chileans. The same images were transformed in murales in several cities. The Christian Democrats ordered to print and to freely distribute about 100,000 copies of Pius XI's anti-Communist encyclica Divini Redemptoris, attributing the initiative to anonymous citizens.

The Radical Party was infiltrated by agents provocateurs, its members corrupted, with the double result of violence in the streets and sabotage of the long-dreamed-of Radical-Socialist alliance. Mass communication played a key role during the terror campaign. The first election week saw more than 40 radio stations – only in the Santiago province – taking part in the anti-Allende operation by broadcasting anti-Communist spots – 20 per day –, fake news – 24 per day – and unfriendly talk shows – 26 per day. It worked. Frei Montalva was elected with 56% of the vote, setting a still-unbroken record. However, his very poor economic performance eventually paved the way for Allende's victory six years later.

The fearmongering strategy was used again on the eve of, and during, the 1970 elections. It all started in October 1969, that is 11 months before the elections, with the foiling of a military plot – the so-called Tacnazo – backed by CIA, the Edwards family and a number of US multinational corporations. Due to the unpopularity of all the candidates running for presidency, the CIA opted for deteriorating Allende's consensus. American corporations supported the plan by funding the political campaigns of Allende's main challengers and by helping them with spin doctors and PR specialists. Against the background of it, a 1964 terror campaign-modeled new season of political violence and mass disinformation. According to the Church Committee, more than 5 million Chileans were reached by the CIA-backed psyops, a critical pool of potential votes if one considers that the country had then a population of 9.5 million.

However, this time the terror campaign didn't work. Allende and his coalition, Unidad Popular (UP), won the elections by getting 36,3% of the vote. Not enough to have the absolute majority in the Congress, but enough to make history: Allende became the world-first Marxist to be democratically elected.

Year One

In the aftermath of the elections, the Nixon presidency ordered Richard Helms to design a coup plan aiming at creating the conditions for a military-led regime change. The 10-million-dollar coup plan was renamed Project FUBELT and attempted to prevent Allende from taking over the presidency through political obstructionism, reality-impacting disinformation and scaremongering. El Mercurio-centered information world began a large-scale FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt) campaign in order to spread the false belief that an economic collapse was around the corner. The disinformation campaign was unprecedented in scale: in the six weeks following the election day, the Church Committee recorded the production and dissemination of 726 anti-Allende news, reportages and articles, that is an average of 17 per day. As a result, a media-driven financial panic took actually place, with hundreds of entrepreneurs closing their bank accounts, tens of investment projects frozen and a lot of speculation – the Santiago Stock Exchange General Index contracted by 50% in less than two weeks. The US fueled the panic by ordering its firms and banks not to renew credits and to freeze loans to needy Chilean companies.

The media-driven financial panic was working, but the decision to speed up Allende's manmade falldown by kidnapping and killing one of his most trusted supporters, the universally appreciated commander-in-chief René Schneider, unexpectedly backfired. The Congress, beyond all expectations, ratified Allende's electoral victory, allowing him to take over the presidency.

Kissinger, the then-National Security Advisor, set the guidelines for the perfect covert warfare in a document renamed “Memorandum 93”. According to Kissinger, Allende would eventually fall if the US corporations stopped investing in the country, if the Chilean currency was attacked by speculation, if the copper price was lowered by speculation – copper was Chile's main exported commodity –, if the progress of the covert operation was monitored on a monthly basis. However, economic warfare alone would lead nowhere in Kissinger's view: the US had to keep investing in psyops, infowars, entryism and subversion.

Returning to Chile, Allende had to deal with a difficult situation since day one: stagnation, inflation, high unemployment, limited stock of international reserves. There was no time to waste, so the presidency set a number of short- and mid-run targets, including inflation reduction, nationalisations, wage growth and economic de-colonisation. In the immediate term, the presidency planned to achieve fast economic recovery through demand-led growth or, as the Ministry of Economic Affairs Pedro Vuskovic said, through a "policy of economic reactivation based upon an income redistribution".

According to Vuskovic and his classmates, the Chilean economy had been colonised by foreign powers – helped by domestic forces – which kept it unproductive on purpose. The new school of economics aspired to free all the foreign-controlled sectors by means of nationalisations and new forms of power sharing. More in detail, Vuskovik wanted to build a workers-based "industrial democracy" (democracia industrial), nay an efficiency-oriented production system based on win-win manager-employee relationships. The experiment seemed to work, at least initially: the output of democratic industries rose by about 15% in 1971 in comparison with the previous year, that is when the experiment hadn't begun yet. Not only workers' committees helped the management improve work methods, lessen inefficiencies and reduce costs, but they also encouraged the workforce to better and faster achieve the targets during the battles for production.

With regard to unemployment and economic colonisation, the government fought the former by launching an expansionary fiscal policy – growth-focused expenditure rose by 70% between 1970 and 1971 – and a number of state-funded projects – about 73,000 housing units built in 1971 against 23,700 of the previous year –, and tried to cope with the latter through a large-scale nationalisation program. The nationalisation campaign aimed at breaking private and foreign monopolies in strategic sectors with the long-term expectation of building a state-centered economy. By 1972, through stock purchases and forced collectivisations, the government had fully nationalised the mining and banking sectors, making the now-public banks change their policies in order to support SMEs and development projects.

The economic warfare was around the corner, Allende knew it – although he underestimated the extent of it –, and the presidency spent the first year working on structural reform of the economy. Besides nationalisations and higher public expenditure, the presidency charged the DIRINCO (Direccion Nacional de Industria y Comercio) and the Price and Supply Committees (JAPs, Juntas de Abastecimiento y Precios) with the responsibility of controlling prices and adjusting wages. JAPs were the early iconic expressions of UP's dream of people's power, as they were usually chaired by housewives tasked with checking the prices of goods and reporting any difference from the official index.

Concerning the foreign economic policy, Allende planned to fund import substitution through an export-oriented strategy. He also oversaw the increase in copper production, Chile's most exported commodity, so as to speed up capital accumulation.

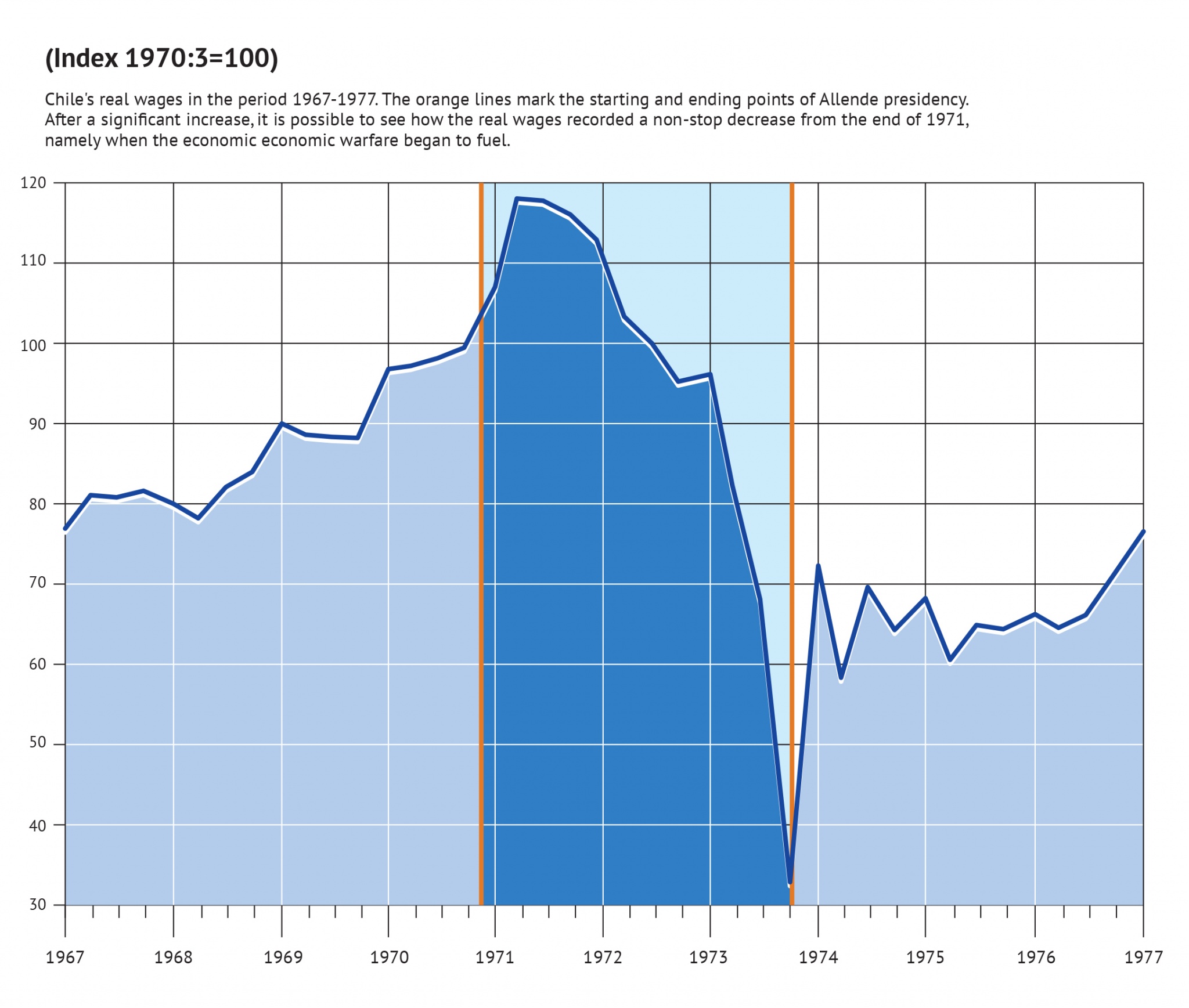

By the mid-year, misled by the lack of effects of the newborn economic warfare, the Allende presidency thought it was on the path to socialism with Chilean characteristics: inflation reduction, wage growth, increase in consumption, economic de-colonisation proceeding at a fast pace. Such a belief would prove wrong in the following six months, hand in hand with the ever-growing extension and internationalisation of the economic warfare.

The economic warfare came to a head in the second half of 1971, quickly nullifying the outcomes of Allende's first year of presidency. Kennecott launched a tacit embargo on Chilean copper. Western countries stopped selling spare parts to Chilean industries and stopped buying Chilean-made goods. The Paris Club started delaying negotiations on the Chilean foreign debt. The world-largest multilateral credit institutions – the US EXIM, World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank – began to refuse any loan application from Santiago de Chile.

Numbers can help understand the magnitude of the invisible embargo: the US EXIM Bank's credits fell from more than $200 million in 1967 to 0 in 1971, US bilateral aid decreased from $35 million in 1969 to $1.5 million in 1971, the Inter-American Development Bank reduced aid from $46 million in 1970 to $2 million in 1972, the World Bank granted no loan for the entire duration of the Allende presidency.

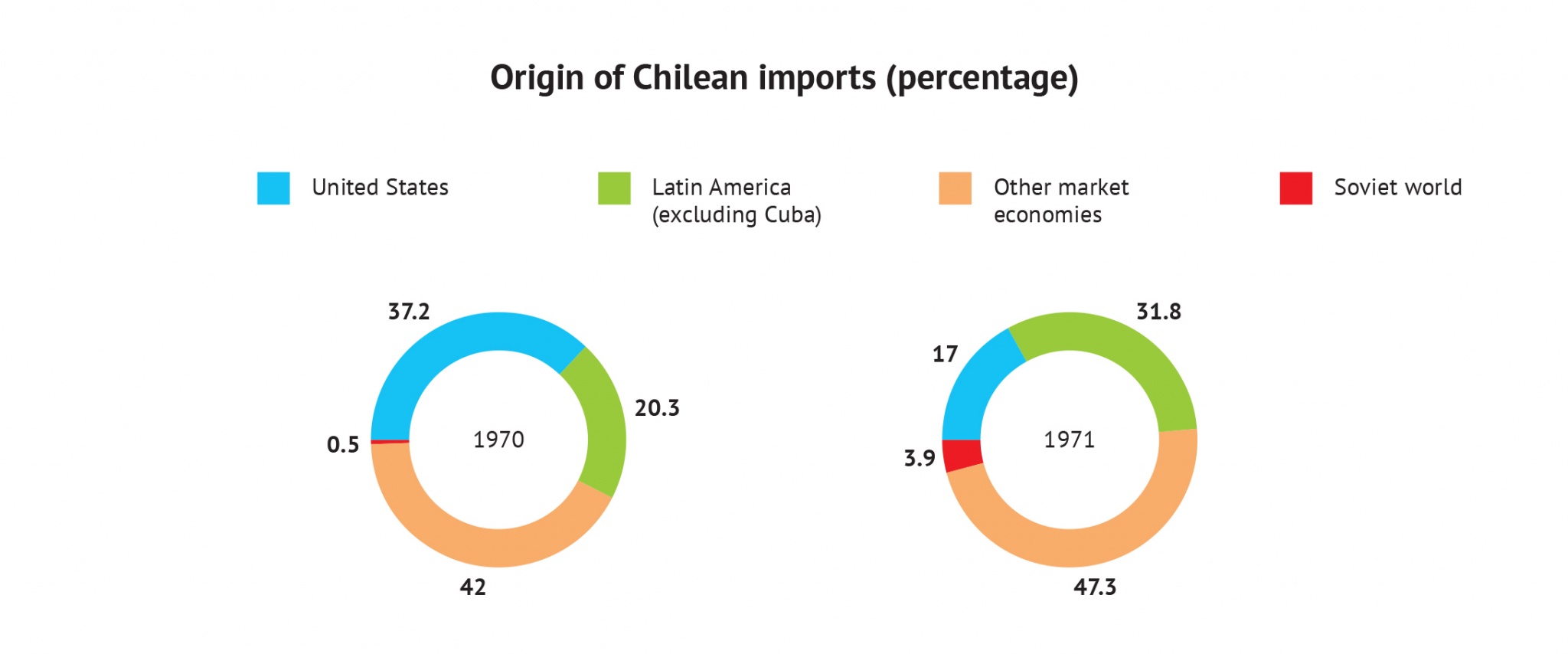

By the end of the year Chilean manufacturers started to feel the effects of the bloqueo invisible, since a high number of industries and the transport system were dependent on foreign technology and Western-imported spare parts. Concurrently with the embargo, the US leveraged on their financial dominance to manipulate copper prices on international markets, with the result of causing $110 million in lost revenue. Allende tried to mitigate the damage by increasing trade with the Soviet bloc and other parts of Latin America, but a quick diversification was impracticable – only the West had the technology Chile was looking for, only the West could provide huge amounts of loans and aid.

Origin of Chilean imports (percentage)

In June, the Congress unanimously greenlighted the nationalisation without compensation of copper industry and of the telecommunications sector. Later that month, the US EXIM Bank refused to issue a loan to the Chilean government, with the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank in tow. Furthermore, the US warned Western partners that buying Chilean copper would result in sanctions.

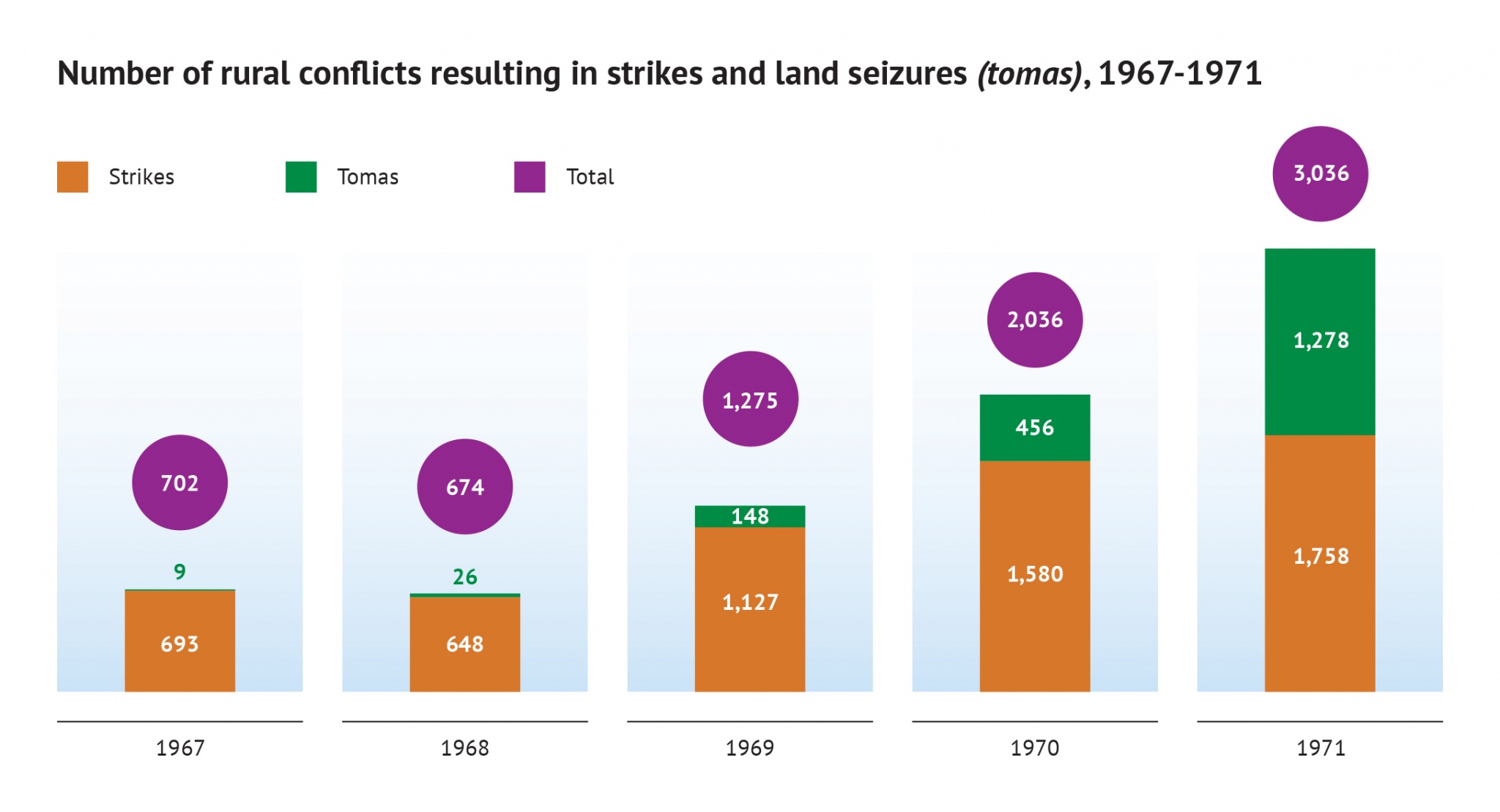

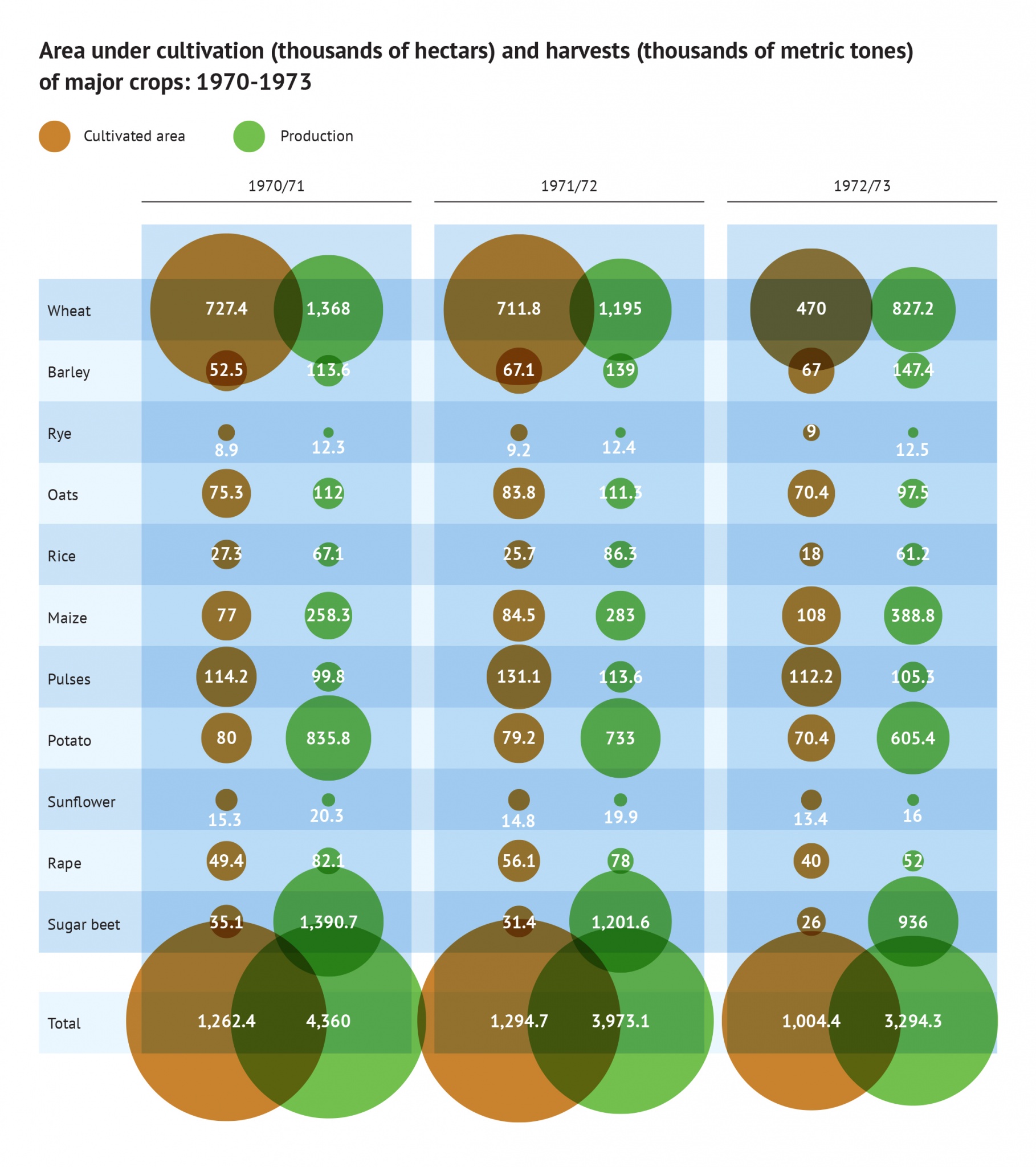

Domestically, Allende had also to face the issue of land occupation and rural violence – both phenomena to be framed in the context of the US-staged boundless warfare. Latifundistas had been expropriated, with their lands given to government-linked cooperative businesses, and the US took advantage of their rage to arm far-right rural militias. As a result, the agribusiness recorded a huge drop in terms of production.

Number of rural conflicts resulting in strikes and land seizures (tomas), 1967-1971

Year Two

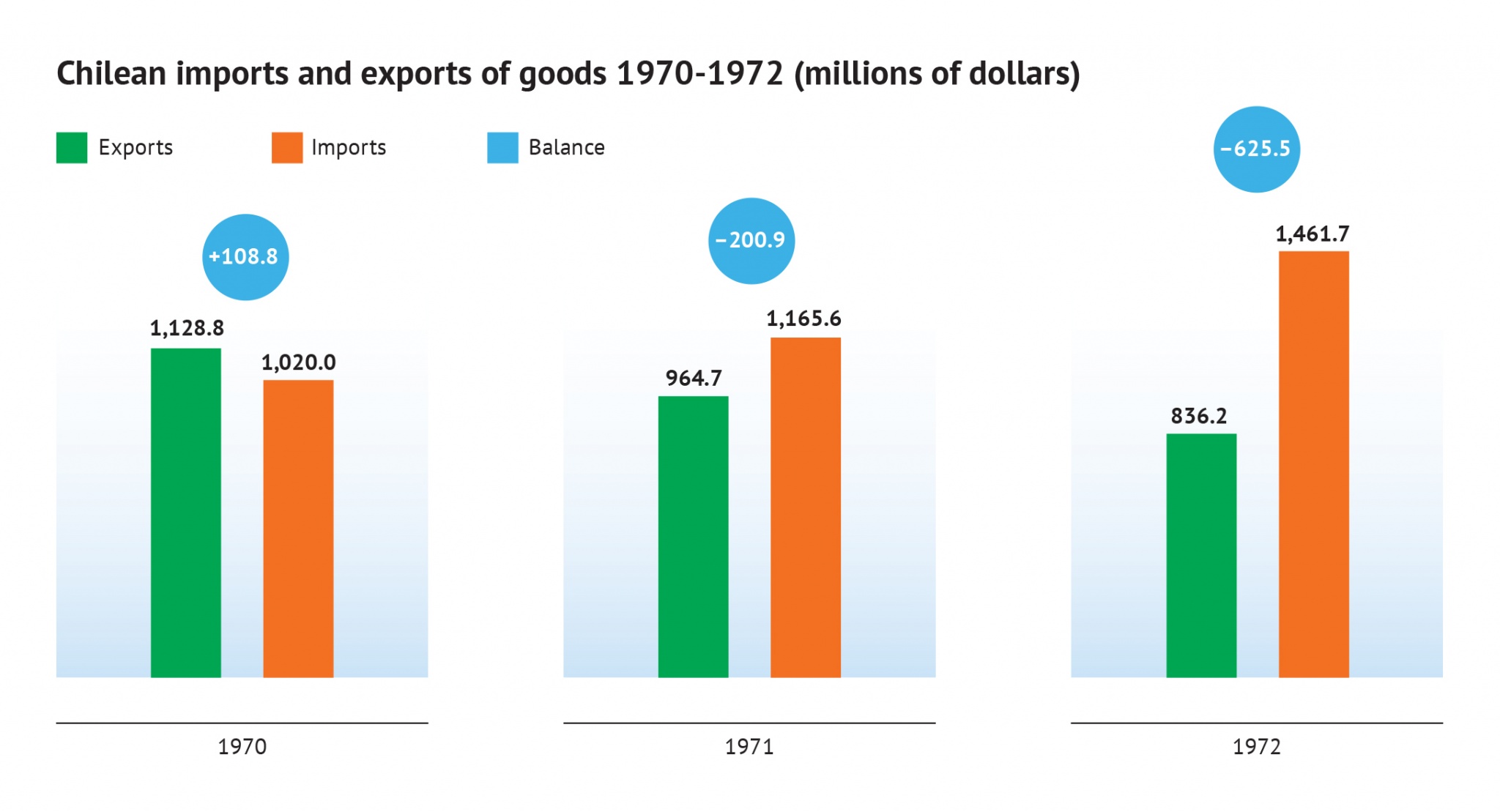

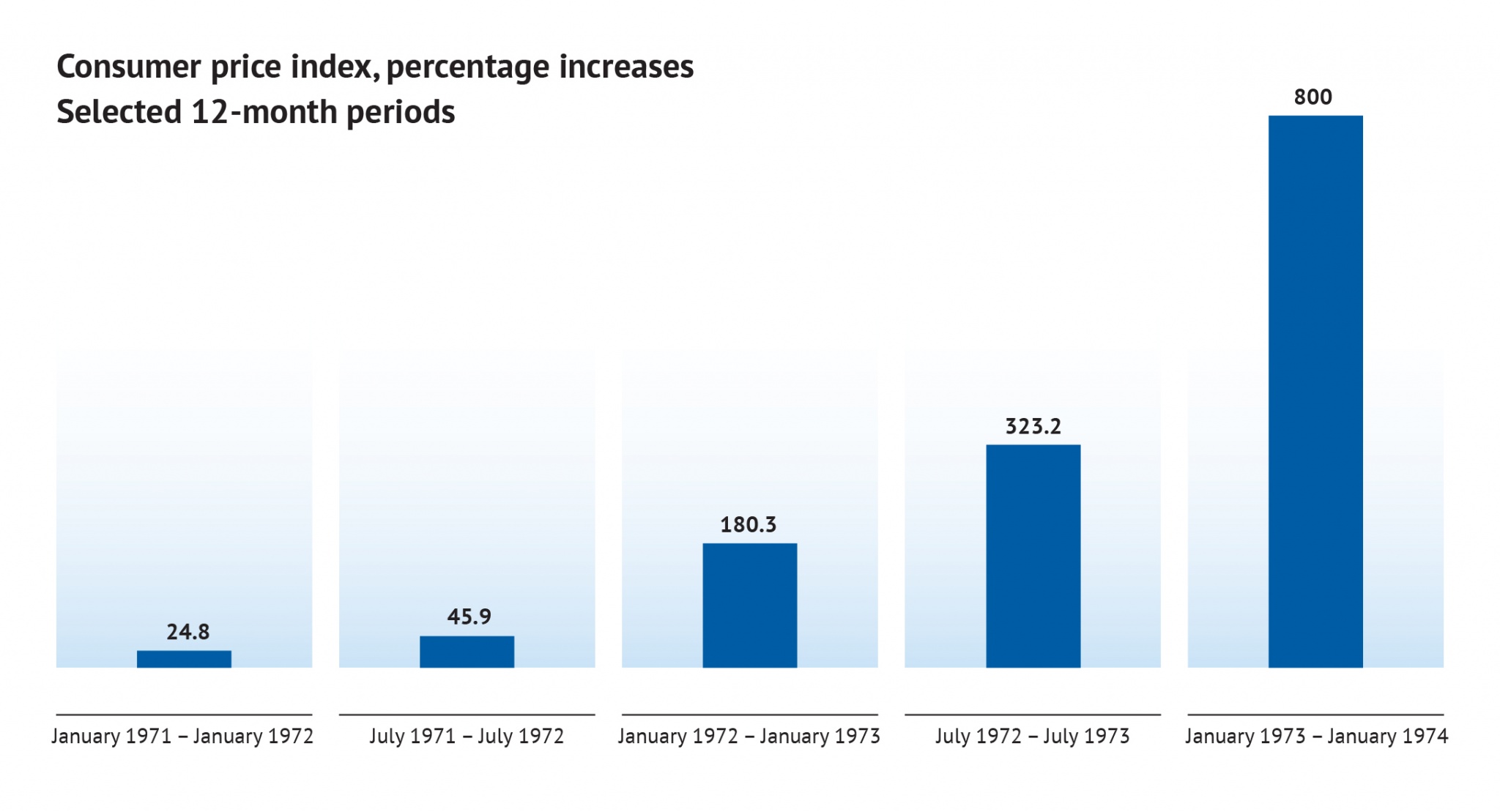

The economic warfare began to bear fruit in 1972. The government had just managed to start improving the living standards by reducing unemployment and increasing average wages, but capital flight, speculative attacks against the national currency and the Invisible blockade would pave the way for a terrific stagflation.

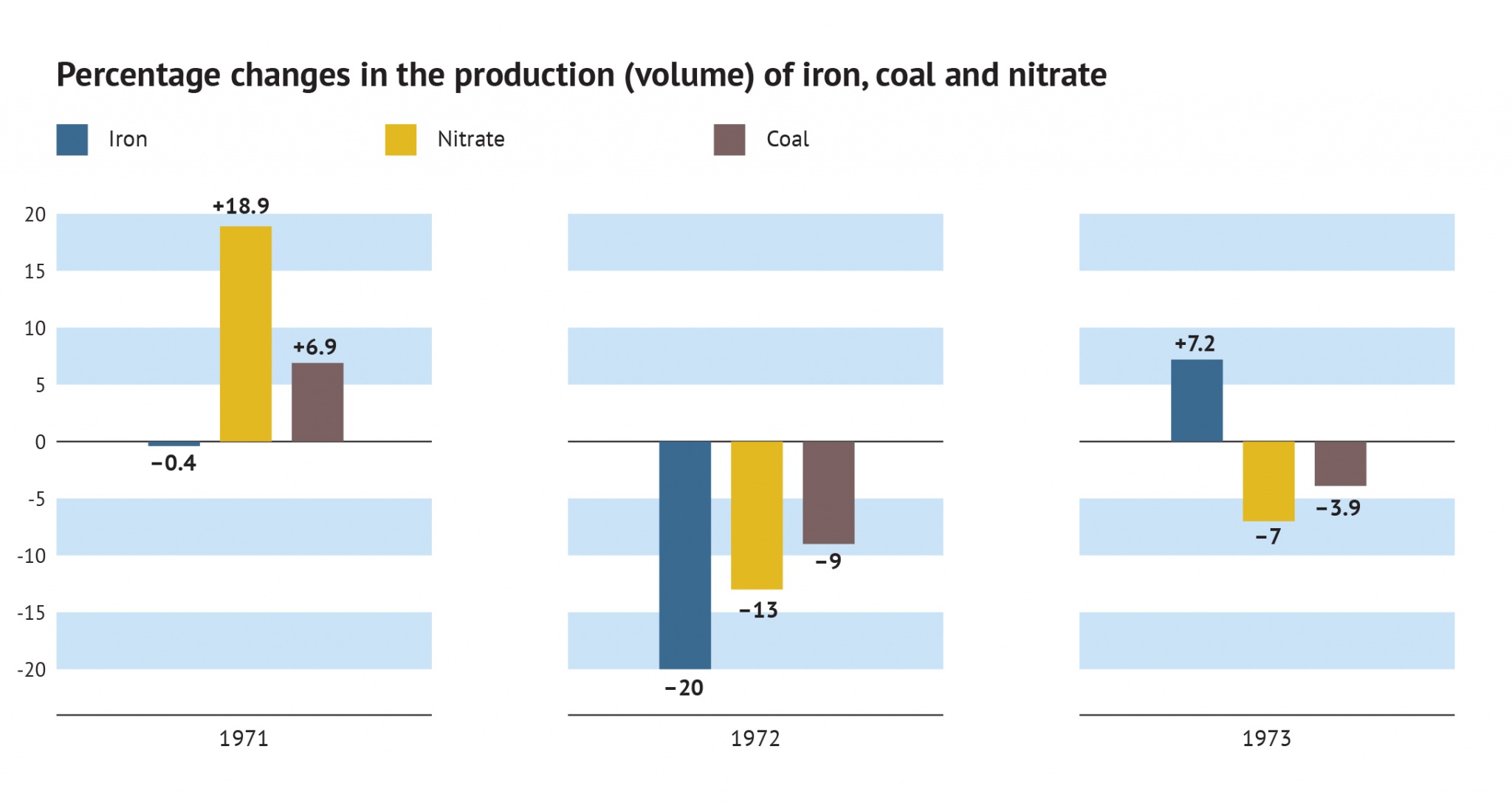

The invisible blockade was hitting Chile very hard: the country used to buy from US producers nearly 40% of its foreign-imported commodities, now the US accounted for less than 10% of foreign trade. Furthermore, Western countries seemed no longer interested in buying Chilean goods, not even copper, and in selling their strategic goods – from fuel to mineral-related machinery. Until then, Chile had imported mineral-related technology exclusively from the US and Western Europe. Now, with the invisible blockade underway, mines found themselves in the middle of a severe crisis because of the sudden lack of spare parts and technology that only the West could provide.

The invisible blockade was complicated by the American call to Chilean experts and high-skilled workers, something already experienced by Cuba in the aftermath of the revolution, which was depriving the country of brains. For instance, Chuquicamata – the world-largest open pit copper mine – witnessed the departure of 97 Chilean experts. The US was attracting Chilean brains by offering them higher salaries, cheap tickets and fast-track visas – and it was working: the US-driven brain drain, extended from mining to other sectors, affected heavily productivity and played a key-role in boycotting Allende's self-sufficiency agenda. Needless to say, fifth columns took advantage of the brain drain-related losses in productivity and efficiency to stage strikes and occupations, further worsening the already precarious situation and leading to a dramatic drop in output. Chuquicamata, the beating heart of Chilean copper industry, recorded 67 forms of boycott throughout the year.

Percentage changes in the production (volume) of iron, coal and nitrate

The Allende presidency tried to revitalise the blockade-hit national industry by launching a series of battles for production, but unsuccessfully – US-corrupted trade unions and captains of industry didn't join the calls, thus preventing the country from circumventing the economic warfare by developing a kind of autarchy.

US and Canadian banks had almost withdrawn from the Chilean market: credits and loans down to $32 million from $220 million of two years earlier. No foreign credit meant no funds to finance the import substitution strategy.

Concurrently with the ongoing economic warfare, the US increased the amount dedicated to psyops, infowars and piloted polarization: $1.6 million to El Mercurio in the period 1971-72 to intensify the propaganda campaign; hundreds of thousands of dollars to entrepreneurial organisations, labor unions and far-right movements to stage mass protests.

In an attempt to cope with the growing number of CIA-backed all-out strikes, the Allende presidency set up the Juntas de Abastecimiento y Control de Precio (JAPs) in April. They were government-managed committees aiming at ensuring food distribution and other basic commodities to needy families.

In the meantime, Kennecott increased anti-Chile lobbyism in Western Europe with the goal of stopping the copper trade, whereas Anaconda urged partners to stop selling spare parts to Chile's major spare part buyer, Codelco, making impossible for it to acquire machinery and relevant tech on the international market. Simultaneously, Allende found himself hostage of an increasingly hostile regional environment, for the ongoing Operation Condor was destabilizing the continent and deprived Chile of important partners such as Bolivia and Brazil.

Chile's real wages in the period 1967-1977.

The economic warfare took place against the background of an ever-increasing social polarisation, resulting from CIA psyops, infowars and entryism. By the end of the year, major cities became open-air battlegrounds – daily shootings, political killings, mass protests, etc – between far-left and far-right movements – with both fronts receiving funds from the US –, the prelude to the quasi-civil war that would break out in 1973.

The situation was not better on political level, where the DC-run Congress started an anti-reform boycott against the presidency's economic agenda destined to last until the coup. Without the Congress approval, Allende could not implement reforms nor could greenlight impacting policies to mitigate the damage provoked by the economic warfare. Another instrument used by the Congress was the impeachment of UP members, destined to grow over time – 2 impeached in 1971, 4 impeached in 1972, 10 impeached in 1973.

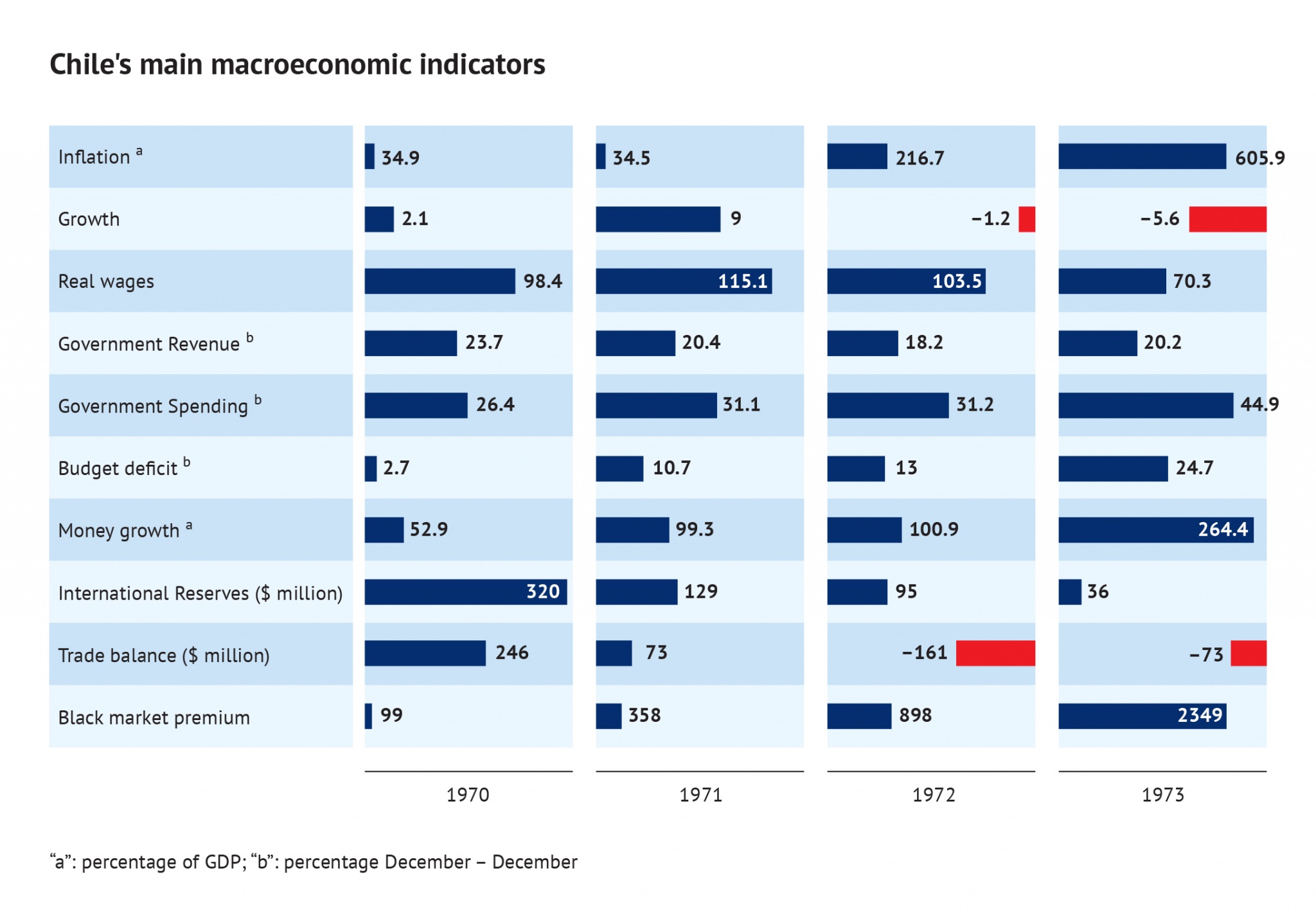

Chile's main macroeconomic indicators

The national economy was about to implode by the end of the year: dramatic expansion of informal economy – less taxes, more speculation –, output decrease, lesser exports, lower FDI inflows and foreign credits. Inflation kept growing without the government being able to control it: labor unions and the DC-run Congress didn't allow the Allende presidency to act decisively.

In August, in an attempt to galvanize the export sector, the presidency opted for a strong devaluation of the national currency – hopefully to boost exports and to use the surplus to adjust budget imbalances – and for a stimulus package designed to increase the productivity in state-owned firms. Lastly, UP economists adjusted public and private wages to counter the devaluation-linked anti-consumption effects.

Chilean imports and exports of goods 1970-1972 (millions of dollars)

The October crisis

The opposition took the opportunity given by the inflationary wave to organize a historical all-out strike which literally killed the national economy. It lasted from 9 October to 5 November, for a total of 26 days. Despite the government's efforts to counter-balance the losses in purchasing power with a 99,8% salary increase for all workers in October, the opposition, the civil society and trade unions staged the "Truckers' strike" (paro de los camioneros), named so because of the key-role played by truck drivers in it.

It's not possible to understand why the truckers' strike succeeded in paralyzing the country and the economy without describing the condition of the transport system and the infrastructure network of that time. The country was – and still is – divided into three regions: the mineral-rich, population-scarce and roadless North and South, and the Greater Santiago area. The latter was – and still is – the core of national economy, well-served by a functioning transport system, home to one third of the total population and import-dependent on the other two regions. The situation was quite different in the North and in the South, where only a bunch of time-consuming routes existed from/to Santiago – it took three days on average to send food from the South to Santiago.

The government proved unable to improve the transport system and the infrastructure network since the invisible embargo hardened the import of spare parts, tires and vehicles, which Chile bought almost exclusively abroad. Long before the October crisis, Allende's foes – the US-linked Patria y Libertad and the truckers' trade union – were already taking advantage of the transport system's contradictions to generate food scarcities in Santiago area. Usually, the saboteurs delayed the shipping times of fruits and vegetables so as to make them arrive spoiled.

The 26-day strike saw the participation of many job categories, including merchants, bus owners and small entrepreneurs. Between 40,000-50,000 truck drivers joined the strike. As a result of the strike, consumers didn't know where to buy necessity goods as most shops closed. A famine seemed likely to occur. The government, eventually, found a way out: the establishment of a nationwide JAPs-run distribution system, with the DINAC tasked with the management, transport and home delivery of low-cost <<popular baskets>>. It was a game-changing pre-modern Amazon-style distribution system set up to confront an emergency situation, but it might have become a stable system if Allende experience had continued.

The October crisis never meant to be a mere truck drivers' strike. Indeed, it was a first-of-a-kind hybrid weapon based on factory occupation, crop destruction, cattle slaughter, attacks on critical infrastructure, with the invisible embargo worsening the already difficult situation by causing shortages of fuel, raw material, fertilizers, etc. The heyday of the economic warfare: impossible to produce, impossible to import, impossible to export.

The national economy proved unable to recover from the October crisis: industrial output decreased in eight factories out of ten, agricultural output reduced by 50%, arable lands resized by 20%, one in three public and private urban buses unusable due to the lack of spare parts. Since the October strike took place during the spring sowing, it is estimated that the market lost about 50% of the then-available crop and 3% of the year-end harvest. In the aftermath of the crisis, Chile found itself less food self-sufficient than in the past and increasingly reliant on food imports.

Year Three

1973 opened with very bad economic data: higher inflation – 22% growth –, higher fiscal deficit – government deficit to GDP ratio at 23% –, less industrial output – 6% decline –, less international reserves – only $40 million left –, lesser US financial engagement – short-term credits dropped by about 60% compared to three years earlier. Internationally, the Escudo was experiencing a never-ending drop in value impossible to capitalise on: the invisible embargo was preventing manufacturers to export their ultra-competitive goods.

It was too late for supplier diversification – Western Europe was joining the invisible embargo, no serious support was sought in the Soviet bloc. No price regulation and no salary adjustment could help – international and domestic speculation would cause the inflationary wave to explode by mid-year.

Consumer price index, percentage increases

The Allende presidency sought to react to the economic crisis by expanding the state-led distribution system of popular baskets and the then-emerging state-owned supermarket chain, but it hadn't resources enough to make them work: saboteurs were increasing the number of land occupations and crop destructions, and there was no way to check all routes and to protect all farms.

The government until then had funded social and economic programs thanks to export earnings and foreign credits, now it had neither. Both the poor and the rich took to the streets to protest – the former for the stop of many poor-only initiatives, like the daily for-free milk delivery, the latter for they felt attacked by the socialist agenda.

By mid-year, while part of the military was planning a coup, the country was on the verge of civil war: non-stop all-out labor strikes of many categories – truck and bus drivers, traders, miners, factory workers, etc –, weekly protests of students and civil society organisations, ever-growing terrorism and political violence by far-left and far-right groups.

Food scarcity had become a serious issue: land occupations, boycotts and crop destructions were killing the agribusiness, and the state didn't exert control on enough farms to reverse the trend and to make the JAPs-run distributing system work.

Area under cultivation (thousands of hectars) and harvests (thousands of metric tones) of major crops: 1970-1973

The events of the summer were the prelude to what would happen in September: an attemped coup in June – the so-called Tanquetazo –, the commander Arturo Araya's homicide – with the mass media claiming that his death was the result of a Cuban plot –, a character assassination campaign leading to the replacement of loyalist Carlos Prats with Augusto Pinochet, non-stop all-out strikes – including the 63-day strike of copper miners –, protests, acts of sabotage and terrorism.

The hot summer gave the final blow to the dying national economy: the CIA invested heavily in the promotion of cross-sectoral labor strikes, getting as a result the participation of more than 250,000 people – on average – in almost daily protests. When the government was finally obliged to stop exporting copper to the world due to the terrific two-month strike of copper miners, that was the sign that Kissinger had finally managed to fulfill Nixon's wish: the Chilean economy was screaming, the entire world could hear it.

On September 11, fearing the outbreak of civil war, the army deposed Allende. He died during the coup, with the cause of his death still a matter of dispute. The rest is history.

[article id="19716"]

Conclusions

"All inflation-and-chaos interpreations are full of pitfalls [...] and without a proper understanding of Chile's political reality and of the political reasons behind the economic crisis that developed they can lead to the wrong conclusions that the whole UP experiment failed for lack of good economists."

(Stefan De Vylder)

Chile is the self-proving evidence that the building of sanctions-proof economic systems may not be enough: in the era of hybrid and boundless wars, where everything can be weaponised, the ultimate goal must be the development of coup-proof systems. Indeed, it's useless to have a strong economy but a weak political system.

This analysis started before 1970, showing how the US had started infiltrating Chile long before Allende's election victory, because aimed at showing – and proving – that economic wars, sometimes, are nothing more than the piece of a larger puzzle. As for the lessons we've learnt from this puzzle, the most important ones are the following:

The UP should have invested in the development of two concepts that seemed to work, nay “people's power” and “democratic factories”, whose mixed nature – an organisational model halfway between capitalism and socialism – and whose initial success – only stopped by the hybrid war – make a study on them worthwhile. At least initially, workers-run committees helped the government raise output levels. Such a model, if adapted and updated, might prove useful in work contexts plagued by labor conflicts, oligopolies and underproductivity.

Spend resources wisely. The government invested too much in a short-term shock therapy with the goal of fueling a fast economic recovery, leaving little for the mid-term and for impacting policies – import substitution, income redistribution, etc – that might have proved fundamental in sabotaging the US plans.

In times of war, use any means possible. Allende did know he was dealing with a never-seen-before boundless warfare, ranging from political subversion to economic boycotts, but despite this he never capitalised on taking over the banking system – which might have helped him fight inflation and speculation properly – and he left the JAPs underdeveloped. JAPS, just like democratic factories, deserve a deeper study for they were successful, at least initially.

Diversification is salvation. Allende did not take the opportunity to follow in Cuba's footsteps and develop a life-saving relationship with the Soviet bloc. Conversely, he opted for trading with Latin America – although the neighboring economies could not be really useful because similar to the Chilean one – and for a timid exposure in the Soviet bloc, perhaps because he hoped to be able to reach a compromise with the US or to win the hybrid war. A stronger partnership with the USSR would have meant credits, loans, aid, know-how, barter, copper-for-something deals; it would have helped speed up the import-substitution agenda.

When in doubt, nationalise. Allende's experience teaches that nationalisations are the quickest and most effective way to oust foreign forces from strategic sectors, or in other words: the best and safest way to de-colonise the economy. But they need to be carried out wisely: UP spent so much time – and resources – nationalising the banking system and the mining sector that several key-sectors were neglected, such as transport, agriculture and wholesale trade, with their vulnerability subsequently weaponised by the US.

Economic strength is a matter of knowledge. Chilean companies were largely reliant on foreign knowledge (patents, licenses, etc), foreign technology and foreign workers. American companies did not reinvest profits in training and skilling programs, hiring US nationals to fill managerial roles and resorting to automation to maintain Chilean workers unskilled. When the economic warfare broke out, the Nixon administration ordered US workers to come back home and launched an open door policy for high-skilled Chilean workers. Accompanied simultaneously by the invisible blockade, the US-piloted brain drain had a tremendous impact: barely possible to import foreign knowledge and technology, hard to produce homemade knowledge and technology. Two lessons here: 1) investments in innovation, creativity, education and R&D are the secrets to the success of vibrant economies; 2) never let foreign firms operate in your market without reinvesting part of their profits in training and transfer knowledge for the local workforce.

[article id="19716"]

Conclusions

"All inflation-and-chaos interpreations are full of pitfalls [...] and without a proper understanding of Chile's political reality and of the political reasons behind the economic crisis that developed they can lead to the wrong conclusions that the whole UP experiment failed for lack of good economists."

(Stefan De Vylder)

Chile is the self-proving evidence that the building of sanctions-proof economic systems may not be enough: in the era of hybrid and boundless wars, where everything can be weaponised, the ultimate goal must be the development of coup-proof systems. Indeed, it's useless to have a strong economy but a weak political system.

This analysis started before 1970, showing how the US had started infiltrating Chile long before Allende's election victory, because aimed at showing – and proving – that economic wars, sometimes, are nothing more than the piece of a larger puzzle. As for the lessons we've learnt from this puzzle, the most important ones are the following:

The UP should have invested in the development of two concepts that seemed to work, nay “people's power” and “democratic factories”, whose mixed nature – an organisational model halfway between capitalism and socialism – and whose initial success – only stopped by the hybrid war – make a study on them worthwhile. At least initially, workers-run committees helped the government raise output levels. Such a model, if adapted and updated, might prove useful in work contexts plagued by labor conflicts, oligopolies and underproductivity.

Spend resources wisely. The government invested too much in a short-term shock therapy with the goal of fueling a fast economic recovery, leaving little for the mid-term and for impacting policies – import substitution, income redistribution, etc – that might have proved fundamental in sabotaging the US plans.

In times of war, use any means possible. Allende did know he was dealing with a never-seen-before boundless warfare, ranging from political subversion to economic boycotts, but despite this he never capitalised on taking over the banking system – which might have helped him fight inflation and speculation properly – and he left the JAPs underdeveloped. JAPS, just like democratic factories, deserve a deeper study for they were successful, at least initially.

Diversification is salvation. Allende did not take the opportunity to follow in Cuba's footsteps and develop a life-saving relationship with the Soviet bloc. Conversely, he opted for trading with Latin America – although the neighboring economies could not be really useful because similar to the Chilean one – and for a timid exposure in the Soviet bloc, perhaps because he hoped to be able to reach a compromise with the US or to win the hybrid war. A stronger partnership with the USSR would have meant credits, loans, aid, know-how, barter, copper-for-something deals; it would have helped speed up the import-substitution agenda.

When in doubt, nationalise. Allende's experience teaches that nationalisations are the quickest and most effective way to oust foreign forces from strategic sectors, or in other words: the best and safest way to de-colonise the economy. But they need to be carried out wisely: UP spent so much time – and resources – nationalising the banking system and the mining sector that several key-sectors were neglected, such as transport, agriculture and wholesale trade, with their vulnerability subsequently weaponised by the US.

Economic strength is a matter of knowledge. Chilean companies were largely reliant on foreign knowledge (patents, licenses, etc), foreign technology and foreign workers. American companies did not reinvest profits in training and skilling programs, hiring US nationals to fill managerial roles and resorting to automation to maintain Chilean workers unskilled. When the economic warfare broke out, the Nixon administration ordered US workers to come back home and launched an open door policy for high-skilled Chilean workers. Accompanied simultaneously by the invisible blockade, the US-piloted brain drain had a tremendous impact: barely possible to import foreign knowledge and technology, hard to produce homemade knowledge and technology. Two lessons here: 1) investments in innovation, creativity, education and R&D are the secrets to the success of vibrant economies; 2) never let foreign firms operate in your market without reinvesting part of their profits in training and transfer knowledge for the local workforce.

Ukraine is the battlefield where the West, Russia and other major players are verily fighting for an epoch-making event: the multipolar transition. Indeed, it was never about Ukraine. Perhaps, the Ukraine war means Ukraine war only for the post-historical European Union, but this conflict has a different and deeper meaning for the rest of the world. The catalysis of the multipolar transition – for Russia and its partners. The prolongation of the dying unipolar moment – for the US.

Opinions

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.