Economic Statecraft

Building a Resistance Economy – Lessons from Napoleon's War on Britain

© Reuters

Ukraine is the battlefield where the West, Russia and other major players are verily fighting for an epoch-making event: the multipolar transition. Indeed, it was never about Ukraine. Perhaps, the Ukraine war means Ukraine war only for the post-historical European Union, but this conflict has a different and deeper meaning for the rest of the world. The catalysis of the multipolar transition – for Russia and its partners. The prolongation of the dying unipolar moment – for the US.

The US is trying to leverage on Russia's “calculation error”, the so-called “military special operation”, so as “to expel it” to Asia, to inhibit its long-term growth and development by means of long-planned unprecedented sanctions, and many other things – tares in the post-soviet space, discontent within Putin's inner circle, etc – but there is much more than this. In fact, the Biden presidency's goal has a lot to do with the EU, more in particular with the Berlin-Paris axis, which is expected to be hit very hard by the anti-Russian sanctions-regime and whose party of detente and strategic autonomy is set to come out of this war greatly resized and weakened. Two birds, the EU and Russia, with one (Ukrainian) stone.

It won't be easy for the EU party of detente and strategic autonomy to re-emerge from the ashes – much will depend on Macron's second presidency and on Germany's Scholz-Greens struggle –, and, probably, there will be no room for diplomatic resets in the years to come. What is known, however, is that much of the Global South has sided with Russia throughout the Ukraine war hopefully to speed up the multipolar transition. Multipolar transition, for the laymen, means many things, among which birth of new polarities, end of dollarocracy, redistribution of power, and rise of a region-based and multi-speed globalization.

The question is: what role will Russia play in tomorrow's world order? The answer is: it depends on Russia's reaction to today's total economic warfare. Because this large-scale multisectoral warfare, ranging from energy to finance, has inadvertently turned Russia into the laboratory of a first-of-a-kind experiment. Tomorrow's economists, scholars and policy-makers will study carefully Russia's response to the West-staged economic warfare with the goal of understanding how to build sanctions-proof national economies. And Russia itself needs to draw on the past if it does want to pass the stress test, as the past offers a lot of examples of both successful and unsuccesful economic resistance, starting from the United Kingdom's economic survival strategy against Napoleon's Continental Bloc.

Circumvent, diverge, divide

On 21 November 1806, Napoleon, by issuing the Berlin Decree, enacted the world-largest embargo ever against the United Kingdom. The Berlin Decree established the so-called Continental System, a Europe-wide blockade forbidding France-aligned European countries to import British goods. Initially the embargo seemed to work: the British withdrew from Europe and in a few months the exports to the continent fell by half. But over time the British found three ways to break the international isolation: circumvention, diversification and diversion. In a few years the UK was capable of replacing the trade with Europe by deepening the ties with overseas colonies and the rest of the world. A life-threatening challenge was turned into a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create a still existing symbiotic metropolis-peripheries relationship – ie the Commonwealth.

While the UK gradually recovered from the blockade, France-centered Continental System suffered more and more because of Europe's over-reliance on British imports, from textile to technology. The economic troubles fueled smuggling, prompting Napoleon to intervene, even militarly, as it occurred in Spain. But, eventually, sabotage and imperial overstrech weakened Paris' capability of controlling the Old Continent and quickened Napoleon's downfall.

The UK experienced a pre-modern economic encirclement, a pre-modern form of containment, and turned the isolation from Europe, which was London's main trade partner, into an opportunity to expand into new markets, to strengthen national industries, and to shape its future vital space.

Napoleon's desires never materialised: the UK experienced no high inflation, no stagnation, no economic crisis, no bankruptcy. Conversely, the Continental System would prove crucial in fueling the UK's extraordinary political and economic growth throughout the 19th century.

The early years

The French and the British were already at war, commercially speaking, since before the Berlin Decree. Indeed, the first European ports were closed to the British during the early 1800s and a number of punitive duties were already in place. Curiously, shortly before the Berlin Decree, the French and their vassals banned the import of English-made cotton products, like clothes, calicoes and muslins, hopefully to hit the British textile industry – one of the engines of the industrial revolution – in order to provoke such an unemployment rate to give rise to labour-related riots in the short-term. But the much-wanted protests never materialised.

Eventually, on November 11, 1806, the French emperor issued the Berlin Decree, marking the official birth of the Continental Blockade. The document was composed by four points:

The blockade of clay

Theoretically, the entire Old Continent should have stopped trading with the UK, but Napoleon's ambitions clashed almost immediately with the difficulty to patrol European coasts and to find reliable and incorruptible officers. In Northern Germany, for instance, merchants continued to trade with the British as if nothing occurred: 1,475 vessels shipping about 590,000 tons of English goods, mostly coal, landed Hamburg between November 1806 and May 1807. No seizure recorded.

Things started to change around mid-1807, when Napoleon fired most of the officers based in German ports and replaced them with loyalists and issued new decrees to tighten the blockade and the penalties for all those found guilty of smuggling.

Against the background of the anti-smuggling fight, the French had another problem to deal with: the supplier diversification-driven price surge. For instance, the Brazilian cotton was much more expensive than the English one: 10–15 francs per kilogram against 6,80–7,30. But it wasn't only the cotton: bristles, flax, hemp, linseed, tallow, tar, timber, etc; the price of such goods rose tenfold and affected both the UK and the Napoleonic system. In any case, it was the former to be the hardest hit – at least in the first two-three years of the blockade. In 1808, England recorded the sharpest reduction of imports of raw cotton, woo, hemp and tallow, which fell respectively by 42%, 80%, 66% and 60%. That same year, the number of poors doubled in Manchester: 44 mills suspended production, 31 halved the working time, only 9 kept running full time.

Napoleon was ready to pay the price for the commercial warfare but he would soon find out that his allies and vassals weren't – the questions are: is Biden today's Napoleon? Can Russia learn from the British experience?. Indeed, the price increases worked contrariwise to the blockade since they encouraged the smuggling and, therefore, helped London recover fast from the shock.

To solve the smuggling problem, between 1810 and 1811 Napoleon proceeded to annex Holland and several German fiefdoms. The overall result was apparently good but verily counterproductive. Indeed, whereas it's true that Napoleon got to extend its direct rule until the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, he had no personnel to patrol the coasts. The annexations led to no significant decline in contraband in Holland, Prussia and Sweden. Similarly, the smuggling flourished in the most southeastern part of the Old Continent, that is the Balkan peninsula.

The British abandoned the legal channels after having understood the potential of smuggling. By means of this strategy, France was hit twice: a) vassals and allies kept receiving British goods whereas Paris experienced shortages, b) the sudden disappearance of English ships stationing in the ports led to the tremendous decrease of customs receipts – a very valuable source of revenue as shown by the numbers: in 1806 France collected 51,200,000 francs from customs receipts, in 1809 only 11,600,000.

Not only smuggling

The UK recovered very fast from the economic shock by pursuing a multipurpose strategy aimed at simultaneously a) increasing the domestic production, b) circumventing the blockade via new routes and smuggling, c) deepening the import-export with the overseas colonies, d) exploiting the maritime supremacy to make it difficult for the French to trade with the Americas.

1808 was the most important watershed moment in the Anglo-French confrontation after Waterloo. The British funded a £500,000 trade structure in Heligoland, a small archipelago in the German North Sea, composed by a port, fortifications and warehouses. It would serve as the main sorting and distribution center for the goods shipped to Northern Europe, covering up to one-sixth of the British total exports annually. Against the background of it, Napoleon launched the Austrian campaign, moving troops from other places, while London smartly funded an anti-French insurrection in Spain. Both events would help the British recover from the economic trauma: the former facilitated the smuggling due to the lesser patrols and the latter would open up the Latin American markets to the UK.

In March 1809, the British diplomacy got to convince the US to repeal the Embargo Act by issuing the Non-Intercourse Act, which led to the fast resume of bilateral trade and to the shipment of goods via alternative and longer routes. When the US completed suspended the embargo three months later, the UK ordered an extraordinary quantity of cotton to bring the national factories back to production.

Against the background of smuggling and circumvention attempts, the British weaponized the mounting anti-French discontent across Europe by funding armed uprisings wherever the prospect for success were high. More than £32,000,000 were sent to Europe between 1808 and 1810 so as to distract Napoleon. The lesson is pretty clear: sometimes you need to set a fire in the periphery if you want to diverge your enemy's attention from the centre.

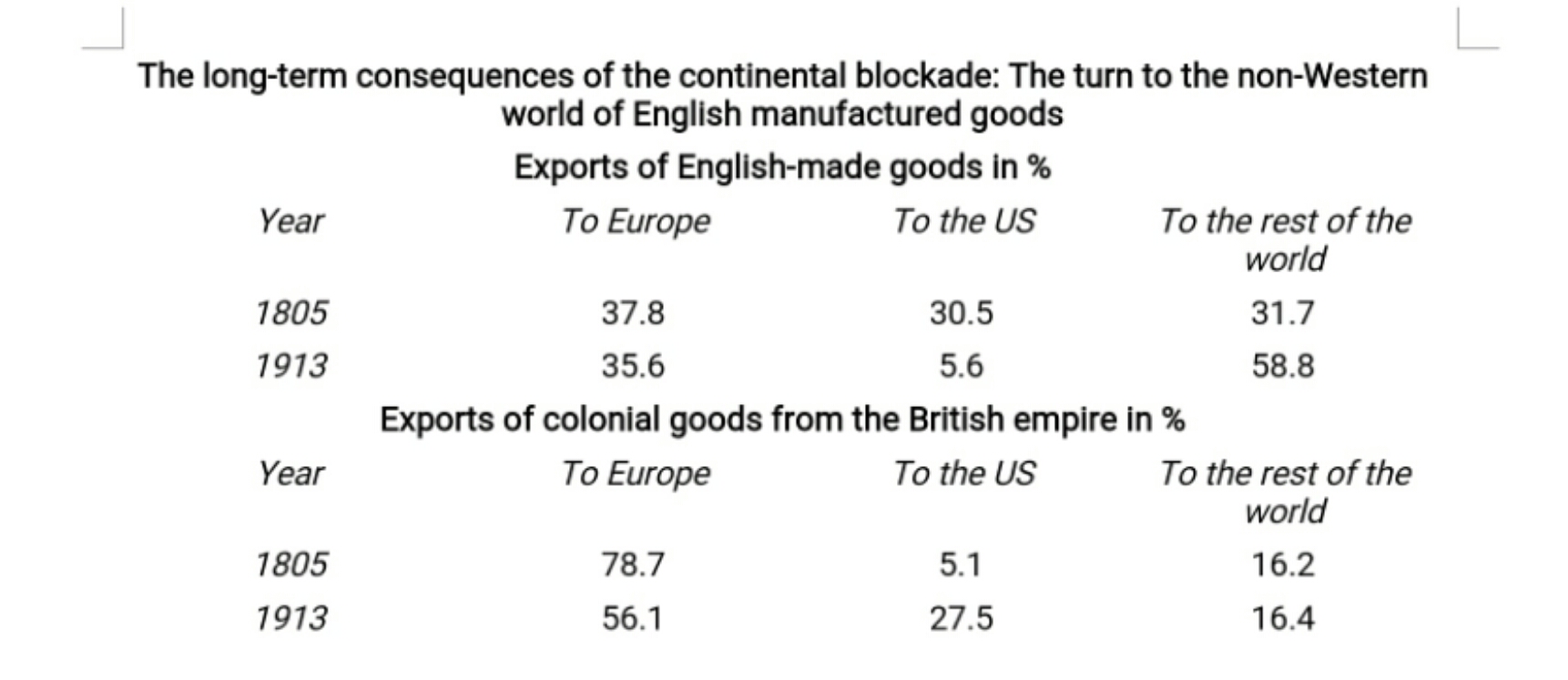

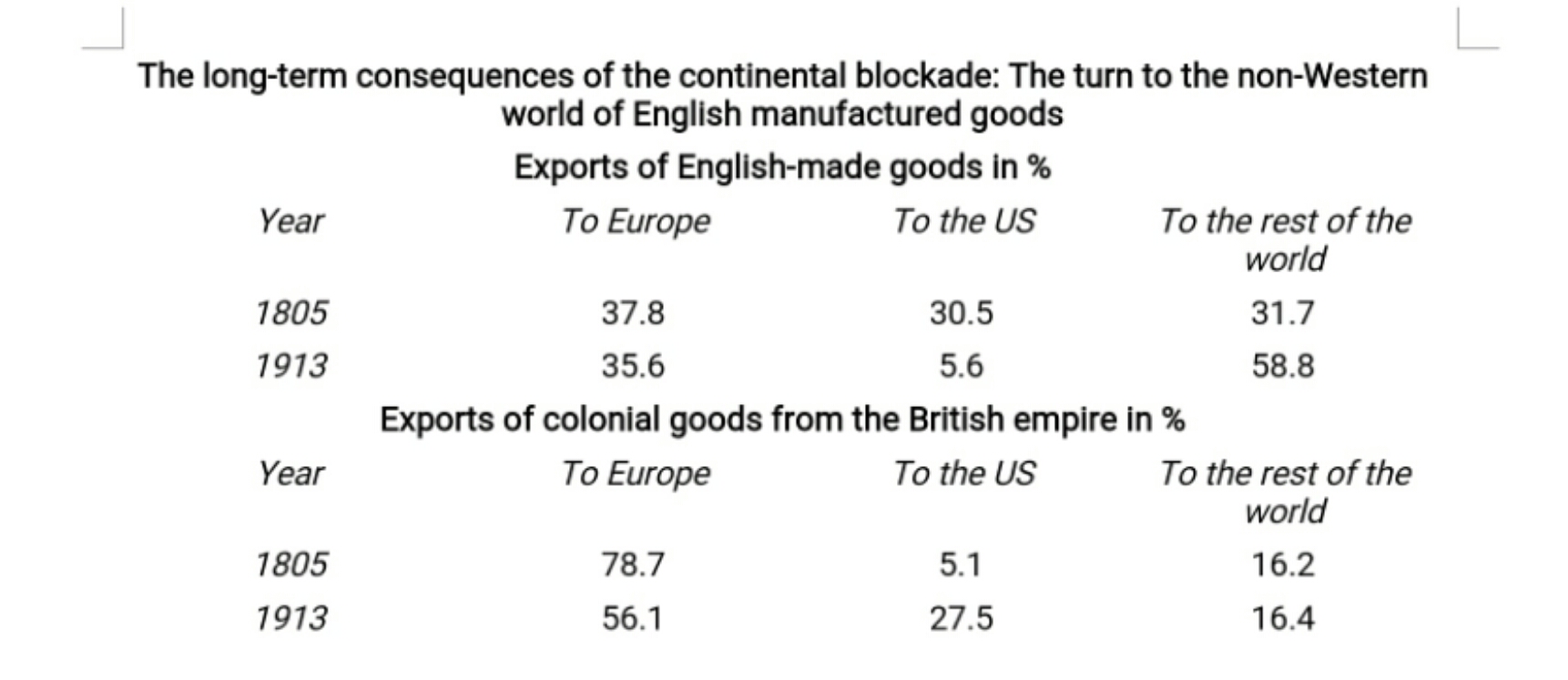

The most considerable success of the “distraction strategy” was obtained in Spain, where a violent insurrection broke out in 1808 which put an end to both the French domination and Napoleon's colonial ambitions over Latin America. The British got to replace quickly the French in the trade with the Spanish colonies and leveraged on their maritime primacy to take over all French dominions by 1811. From that date on, the UK would establish a strong commercial presence destined to last decades, gaining access to large resource-hungry markets like Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. Besides Latin America, the UK would also start to commercially expand to Southeastern Asia and Africa. In short, the very foundations of the modern-day Commonwealth and of the UK's peculiar transnational (or transcontinental?) position in the world economy were laid during these years.

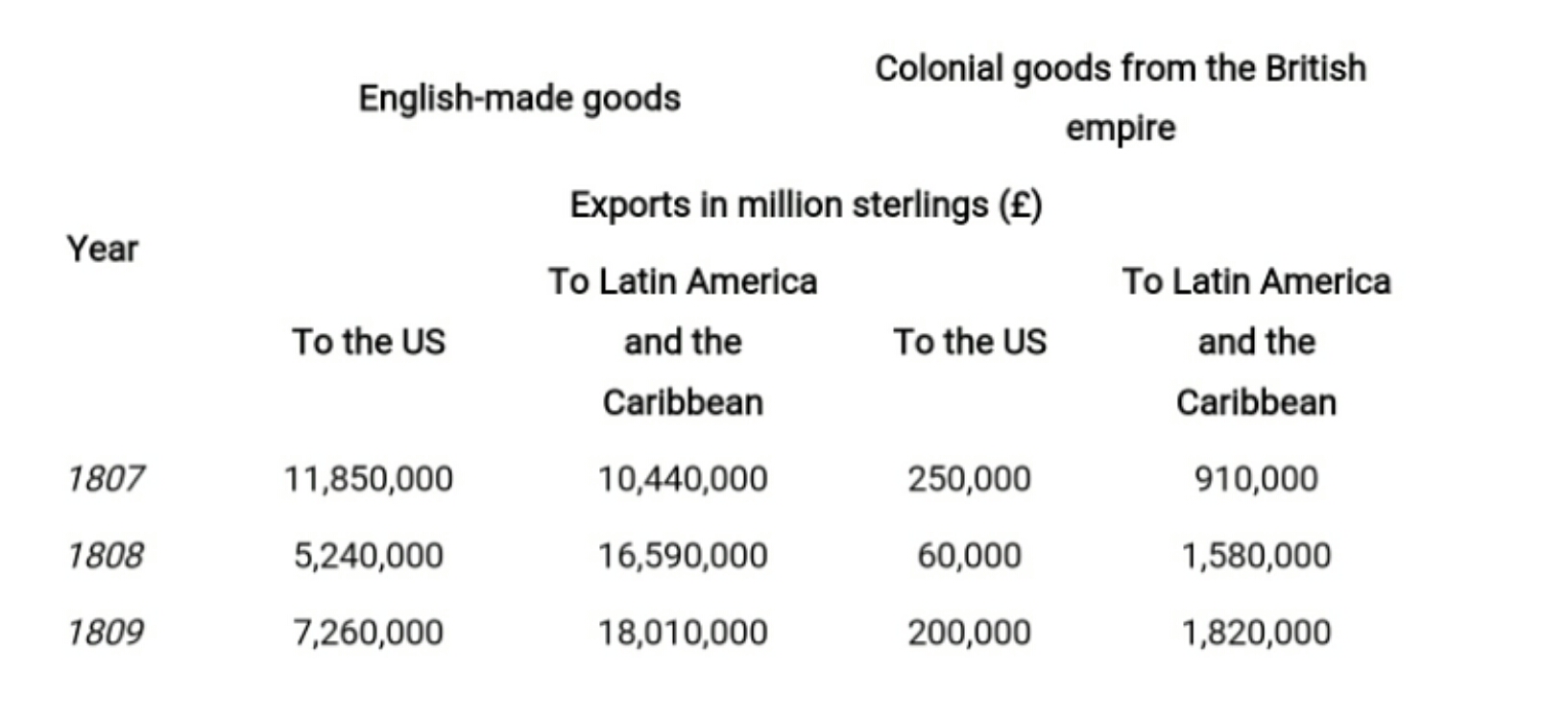

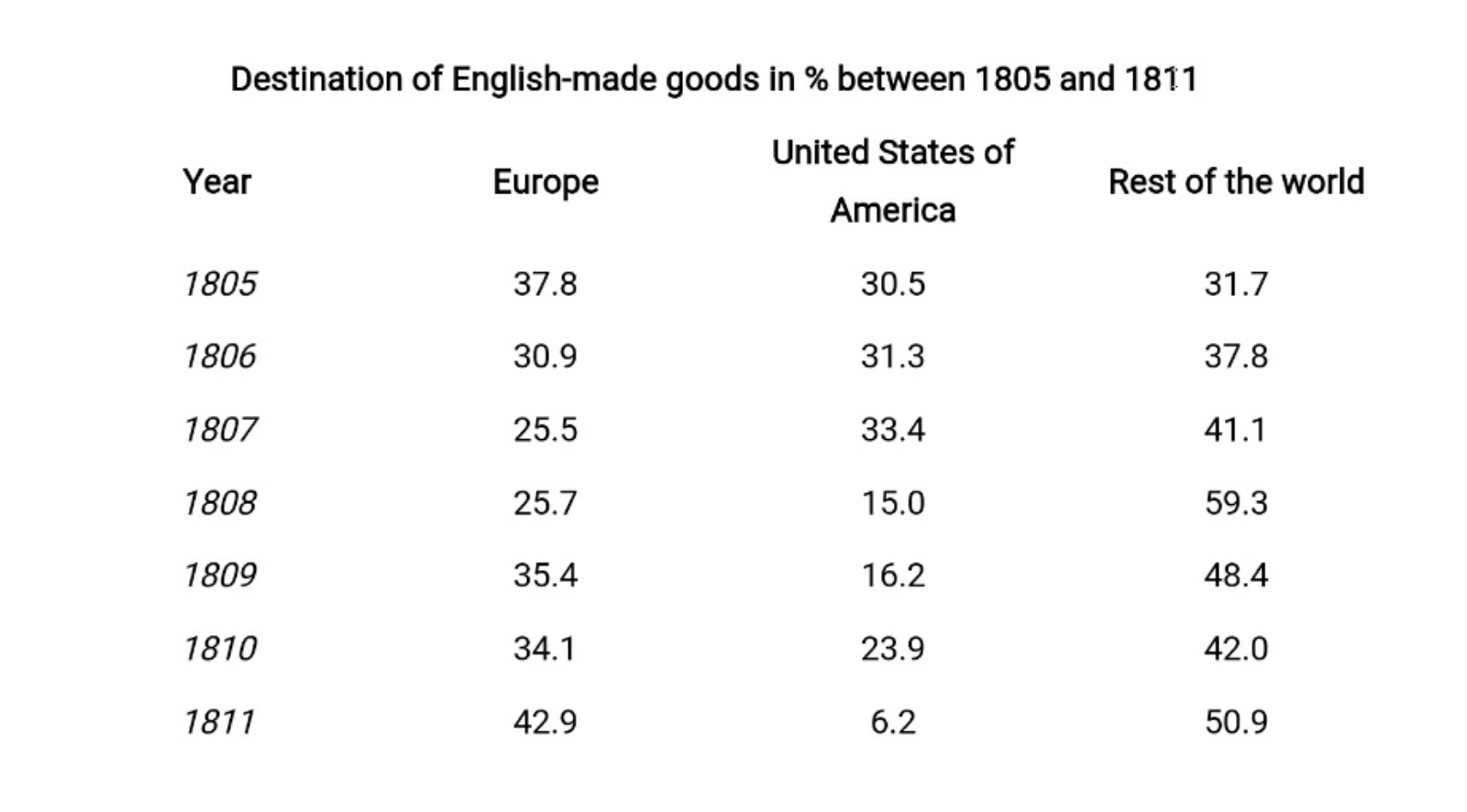

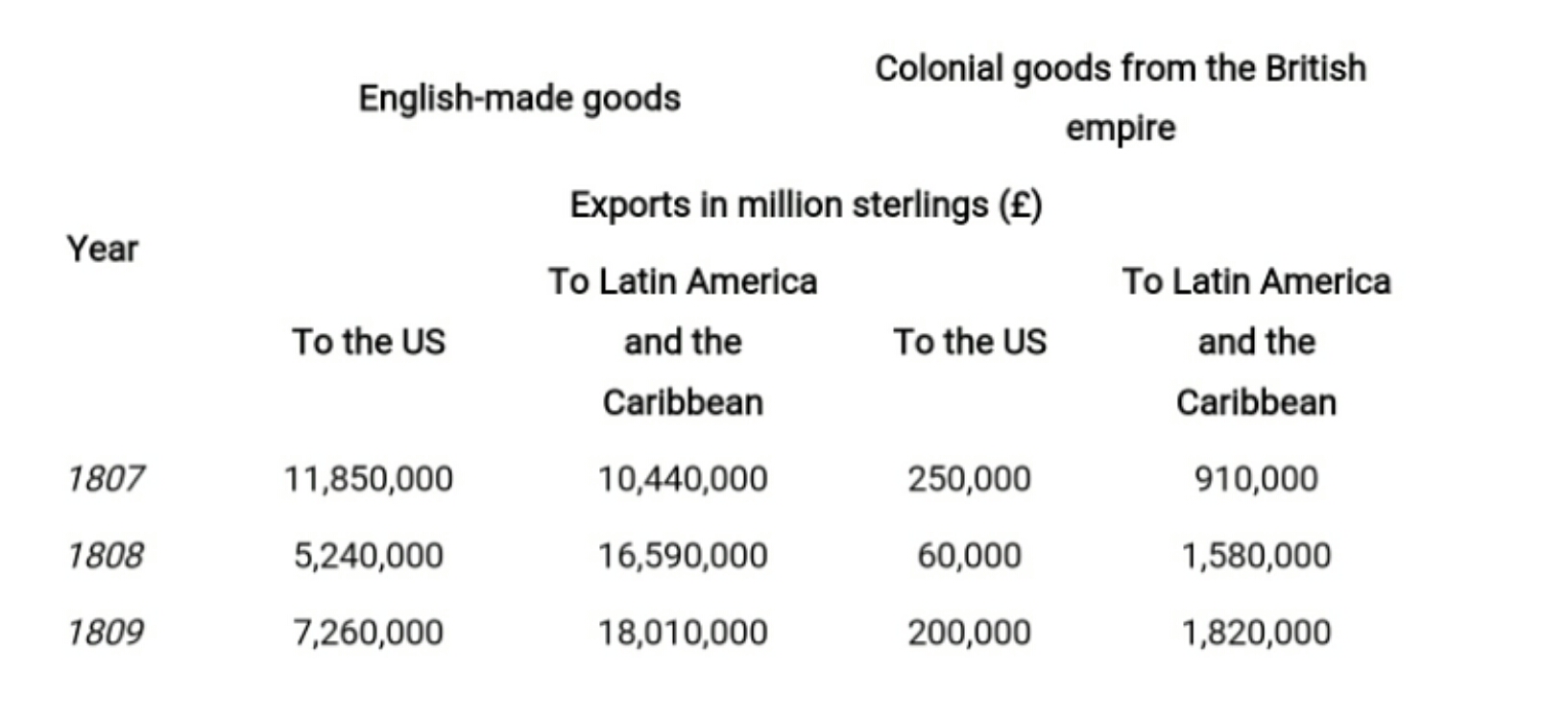

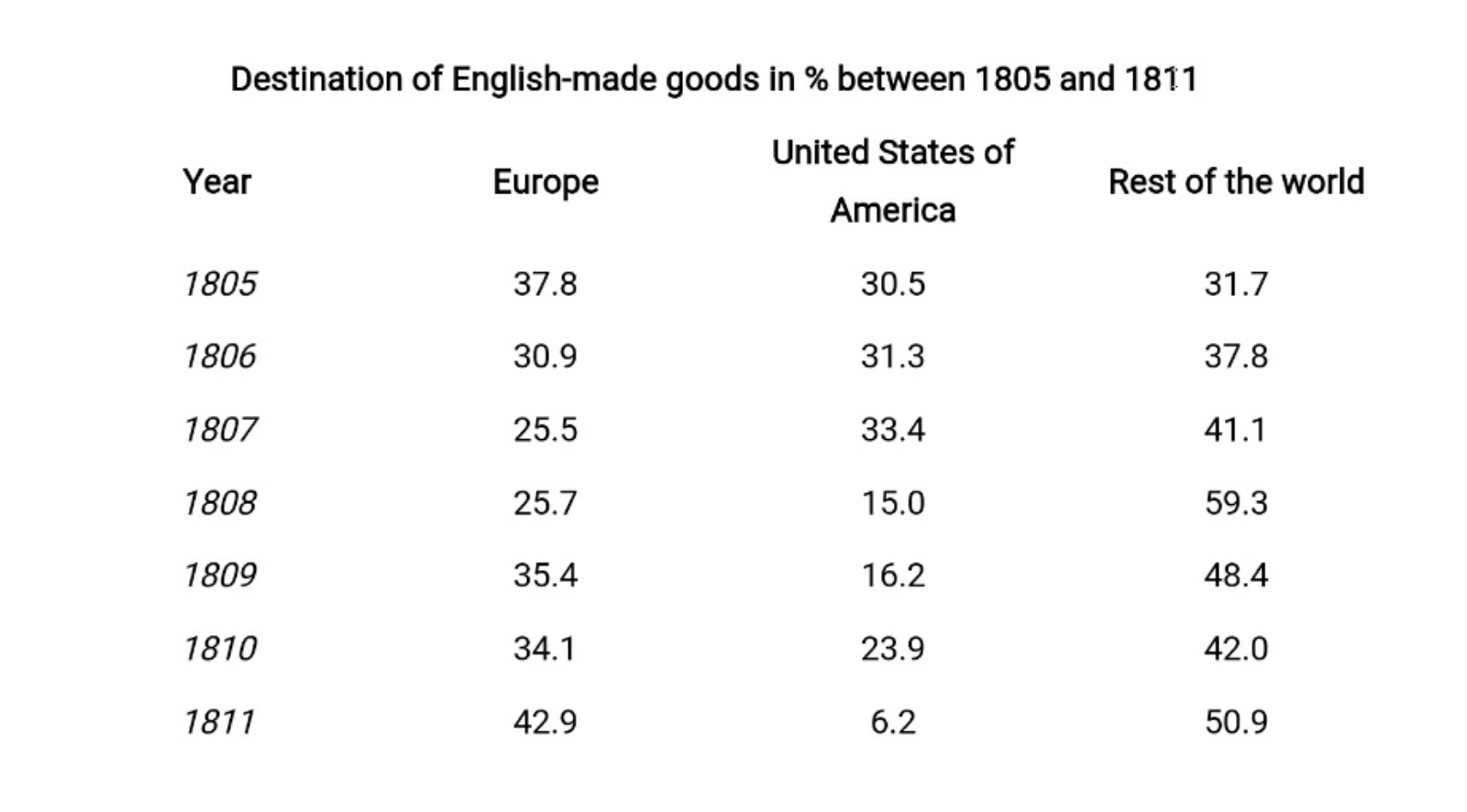

The “pivot to the world” and the increase of contraband galvanized domestic factories to raise the production levels, absorbing and subsequently nullifying the damage of the blockade. Between 1808 and 1810, supported by the outstanding demand boom, some productions grew by 50% – the export value of manufactured goods rose from £12,500,000 to £18,400,000 – and others by more than 100% – the export value of yarn increased from £470,000 to £1,020,000. And from 1803 to 1811, as it will be understandable after reading the table below, the importance of non-European markets increased significantly.

France's mistakes

Napoleon committed a number of fatal mistakes throughout the economic war on the United Kingdom. More in detail, he overestimated his ability to control a continent-wide blockade; he fought simultaneously on many fronts until he reached the point of no return – imperial overstretch –; he didn't devote attention and resources to self-sufficiency and import-substitution; and he was blinded by what the American strategist Edward Luttwak defined the “great state autism”, namely the historical inability of major powers to read reality objectively and to listen to, and take care of, the interests of small-but-important junior partners and satellites.

Napoleon's first and foremost problem is universally known to everyone: great military leader, bad economist. Never made proper use of the tens of tons of English-made goods captured during the thousands of search-and-seizure operations. Never exploited the English know-how in his possession. No effort to reduce the costs of supplier diversification. No investments in import-substitution. No attention to the empire's peripheries.

French factories were initially ordered to increase the production but no talk about import substitution took place before the 1810s. When Napoleon changed his mind it was too late: the British had recovered from the blockade, partners and allies were receiving illegally tons of English goods, the continental system was falling apart.

The most ambitious import-substitution project involved indigo, coffee and sugar, but it led nowhere. The prospect of replacing Indian indigo with French-based plantations clashed with the lack of investments and the low output of the existing factories. In 1813 there were three indigo-processing factories in France which together produced 6,000 kilograms. The following year, two of them ceased operations. The same thing happened with sugar.

Ultimately, Napoleon made another severe and meaningless mistake, that is to supply England with foodstuffs. If there's something whose weaponization could have brought the British on the brink of collapse that was precisely the food. Indeed, the UK had an issue in terms of food security – as shown by the episodic food shortages which took place between 1795 and 1812 – and France could – and should – have used such a vulnerability to starve out the rival, forcing it to bargain. The question is: is gas Russia's the equivalent to Napoleon's food?

The UK was particularly worried about the import of European-made corn, but eventually no embargo was ever declared upon it. Conversely, throughout the blockade period, France increased the exports to the UK of cereal products like corn, wheat and grain, in accordance with a merchantilist-inspired food-for-metals policy.

Conclusions

The United Kingdom was heavily dependent on trade with the European mainland and vice versa. The former imported foodstuffs and the latter imported colonial and manufactured goods. The blockade should have equally harmed both of them but it ended up catalysing France's falldown and fostering the British post-Napoleonic economic miracle. Last but not least, London's strategy based on circumvention, distraction and diversification set the ground for the global expansion of the British empire and for the rise of the modern-way Commonwealth.

The British counteroffensive to Napoleon's economic war needs to be re-discovered and to be read for what it is: a source of evergreen lessons on economics and strategy. Of the several lessons that can be drown from this historical episode, three stand out for importance and topicality:

The British resorted at the same time, and with the same vigor, to smuggling and to unconventional guerrilla operations so as to distract Napoleon and to deprive him of resources. Between 1808 and 1810 the British government funded uprisings and insurgencies all over the Old Continent, spending about £32,000,000. These operations proved fundamental in destabilizing the Continental System from within and worked in parallel but complementarily with smuggling. Explained otherwise: economic wars are more about war than economy; indeed, they can be won by playing smarter.

It's fundamental that a major power avoid falling into the great-state autism trap. Discontent can be easily exploited by an artful rival. Spheres of influence can last and withstand external pressures only if metropolis and peripheries are tied by trust-based win-win relations.

The British dealt with the sudden lack of foreign-made goods by increasing the domestic production but at no time the goal was to close themselves from the outer world. The disposal of more goods made it possible to satisfy the illegal demand both from Europe and new markets. It's the self-proving evidence that economic wars can be at the same time a life-threatening challenge and an unrepeatable opportunity – everything depends on the target's reaction. The British found salvation between the Americas and today's Commonwealth, Russia might find it outside the West.

The US is trying to leverage on Russia's “calculation error”, the so-called “military special operation”, so as “to expel it” to Asia, to inhibit its long-term growth and development by means of long-planned unprecedented sanctions, and many other things – tares in the post-soviet space, discontent within Putin's inner circle, etc – but there is much more than this. In fact, the Biden presidency's goal has a lot to do with the EU, more in particular with the Berlin-Paris axis, which is expected to be hit very hard by the anti-Russian sanctions-regime and whose party of detente and strategic autonomy is set to come out of this war greatly resized and weakened. Two birds, the EU and Russia, with one (Ukrainian) stone.

It won't be easy for the EU party of detente and strategic autonomy to re-emerge from the ashes – much will depend on Macron's second presidency and on Germany's Scholz-Greens struggle –, and, probably, there will be no room for diplomatic resets in the years to come. What is known, however, is that much of the Global South has sided with Russia throughout the Ukraine war hopefully to speed up the multipolar transition. Multipolar transition, for the laymen, means many things, among which birth of new polarities, end of dollarocracy, redistribution of power, and rise of a region-based and multi-speed globalization.

The question is: what role will Russia play in tomorrow's world order? The answer is: it depends on Russia's reaction to today's total economic warfare. Because this large-scale multisectoral warfare, ranging from energy to finance, has inadvertently turned Russia into the laboratory of a first-of-a-kind experiment. Tomorrow's economists, scholars and policy-makers will study carefully Russia's response to the West-staged economic warfare with the goal of understanding how to build sanctions-proof national economies. And Russia itself needs to draw on the past if it does want to pass the stress test, as the past offers a lot of examples of both successful and unsuccesful economic resistance, starting from the United Kingdom's economic survival strategy against Napoleon's Continental Bloc.

Circumvent, diverge, divide

On 21 November 1806, Napoleon, by issuing the Berlin Decree, enacted the world-largest embargo ever against the United Kingdom. The Berlin Decree established the so-called Continental System, a Europe-wide blockade forbidding France-aligned European countries to import British goods. Initially the embargo seemed to work: the British withdrew from Europe and in a few months the exports to the continent fell by half. But over time the British found three ways to break the international isolation: circumvention, diversification and diversion. In a few years the UK was capable of replacing the trade with Europe by deepening the ties with overseas colonies and the rest of the world. A life-threatening challenge was turned into a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create a still existing symbiotic metropolis-peripheries relationship – ie the Commonwealth.

While the UK gradually recovered from the blockade, France-centered Continental System suffered more and more because of Europe's over-reliance on British imports, from textile to technology. The economic troubles fueled smuggling, prompting Napoleon to intervene, even militarly, as it occurred in Spain. But, eventually, sabotage and imperial overstrech weakened Paris' capability of controlling the Old Continent and quickened Napoleon's downfall.

The UK experienced a pre-modern economic encirclement, a pre-modern form of containment, and turned the isolation from Europe, which was London's main trade partner, into an opportunity to expand into new markets, to strengthen national industries, and to shape its future vital space.

Napoleon's desires never materialised: the UK experienced no high inflation, no stagnation, no economic crisis, no bankruptcy. Conversely, the Continental System would prove crucial in fueling the UK's extraordinary political and economic growth throughout the 19th century.

The early years

The French and the British were already at war, commercially speaking, since before the Berlin Decree. Indeed, the first European ports were closed to the British during the early 1800s and a number of punitive duties were already in place. Curiously, shortly before the Berlin Decree, the French and their vassals banned the import of English-made cotton products, like clothes, calicoes and muslins, hopefully to hit the British textile industry – one of the engines of the industrial revolution – in order to provoke such an unemployment rate to give rise to labour-related riots in the short-term. But the much-wanted protests never materialised.

Eventually, on November 11, 1806, the French emperor issued the Berlin Decree, marking the official birth of the Continental Blockade. The document was composed by four points:

- The British islands are officially declared under blockade

- The British persons living in French-ruled and -occupied territories are declared under arrest and their properties are confiscated – a pre-modern form of asset freezing

- The import of goods and colonial goods from the British empire is forbidden

- Denied access to European ports to any vessel found to be in trade relations with the British – interestingly, the same measure has been applying by the US since the 1960s to discourage foreign firms from engaging trade with Cuba.

The blockade of clay

Theoretically, the entire Old Continent should have stopped trading with the UK, but Napoleon's ambitions clashed almost immediately with the difficulty to patrol European coasts and to find reliable and incorruptible officers. In Northern Germany, for instance, merchants continued to trade with the British as if nothing occurred: 1,475 vessels shipping about 590,000 tons of English goods, mostly coal, landed Hamburg between November 1806 and May 1807. No seizure recorded.

Things started to change around mid-1807, when Napoleon fired most of the officers based in German ports and replaced them with loyalists and issued new decrees to tighten the blockade and the penalties for all those found guilty of smuggling.

Against the background of the anti-smuggling fight, the French had another problem to deal with: the supplier diversification-driven price surge. For instance, the Brazilian cotton was much more expensive than the English one: 10–15 francs per kilogram against 6,80–7,30. But it wasn't only the cotton: bristles, flax, hemp, linseed, tallow, tar, timber, etc; the price of such goods rose tenfold and affected both the UK and the Napoleonic system. In any case, it was the former to be the hardest hit – at least in the first two-three years of the blockade. In 1808, England recorded the sharpest reduction of imports of raw cotton, woo, hemp and tallow, which fell respectively by 42%, 80%, 66% and 60%. That same year, the number of poors doubled in Manchester: 44 mills suspended production, 31 halved the working time, only 9 kept running full time.

Napoleon was ready to pay the price for the commercial warfare but he would soon find out that his allies and vassals weren't – the questions are: is Biden today's Napoleon? Can Russia learn from the British experience?. Indeed, the price increases worked contrariwise to the blockade since they encouraged the smuggling and, therefore, helped London recover fast from the shock.

To solve the smuggling problem, between 1810 and 1811 Napoleon proceeded to annex Holland and several German fiefdoms. The overall result was apparently good but verily counterproductive. Indeed, whereas it's true that Napoleon got to extend its direct rule until the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, he had no personnel to patrol the coasts. The annexations led to no significant decline in contraband in Holland, Prussia and Sweden. Similarly, the smuggling flourished in the most southeastern part of the Old Continent, that is the Balkan peninsula.

The British abandoned the legal channels after having understood the potential of smuggling. By means of this strategy, France was hit twice: a) vassals and allies kept receiving British goods whereas Paris experienced shortages, b) the sudden disappearance of English ships stationing in the ports led to the tremendous decrease of customs receipts – a very valuable source of revenue as shown by the numbers: in 1806 France collected 51,200,000 francs from customs receipts, in 1809 only 11,600,000.

Not only smuggling

The UK recovered very fast from the economic shock by pursuing a multipurpose strategy aimed at simultaneously a) increasing the domestic production, b) circumventing the blockade via new routes and smuggling, c) deepening the import-export with the overseas colonies, d) exploiting the maritime supremacy to make it difficult for the French to trade with the Americas.

1808 was the most important watershed moment in the Anglo-French confrontation after Waterloo. The British funded a £500,000 trade structure in Heligoland, a small archipelago in the German North Sea, composed by a port, fortifications and warehouses. It would serve as the main sorting and distribution center for the goods shipped to Northern Europe, covering up to one-sixth of the British total exports annually. Against the background of it, Napoleon launched the Austrian campaign, moving troops from other places, while London smartly funded an anti-French insurrection in Spain. Both events would help the British recover from the economic trauma: the former facilitated the smuggling due to the lesser patrols and the latter would open up the Latin American markets to the UK.

In March 1809, the British diplomacy got to convince the US to repeal the Embargo Act by issuing the Non-Intercourse Act, which led to the fast resume of bilateral trade and to the shipment of goods via alternative and longer routes. When the US completed suspended the embargo three months later, the UK ordered an extraordinary quantity of cotton to bring the national factories back to production.

Against the background of smuggling and circumvention attempts, the British weaponized the mounting anti-French discontent across Europe by funding armed uprisings wherever the prospect for success were high. More than £32,000,000 were sent to Europe between 1808 and 1810 so as to distract Napoleon. The lesson is pretty clear: sometimes you need to set a fire in the periphery if you want to diverge your enemy's attention from the centre.

The most considerable success of the “distraction strategy” was obtained in Spain, where a violent insurrection broke out in 1808 which put an end to both the French domination and Napoleon's colonial ambitions over Latin America. The British got to replace quickly the French in the trade with the Spanish colonies and leveraged on their maritime primacy to take over all French dominions by 1811. From that date on, the UK would establish a strong commercial presence destined to last decades, gaining access to large resource-hungry markets like Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. Besides Latin America, the UK would also start to commercially expand to Southeastern Asia and Africa. In short, the very foundations of the modern-day Commonwealth and of the UK's peculiar transnational (or transcontinental?) position in the world economy were laid during these years.

The “pivot to the world” and the increase of contraband galvanized domestic factories to raise the production levels, absorbing and subsequently nullifying the damage of the blockade. Between 1808 and 1810, supported by the outstanding demand boom, some productions grew by 50% – the export value of manufactured goods rose from £12,500,000 to £18,400,000 – and others by more than 100% – the export value of yarn increased from £470,000 to £1,020,000. And from 1803 to 1811, as it will be understandable after reading the table below, the importance of non-European markets increased significantly.

France's mistakes

Napoleon committed a number of fatal mistakes throughout the economic war on the United Kingdom. More in detail, he overestimated his ability to control a continent-wide blockade; he fought simultaneously on many fronts until he reached the point of no return – imperial overstretch –; he didn't devote attention and resources to self-sufficiency and import-substitution; and he was blinded by what the American strategist Edward Luttwak defined the “great state autism”, namely the historical inability of major powers to read reality objectively and to listen to, and take care of, the interests of small-but-important junior partners and satellites.

Napoleon's first and foremost problem is universally known to everyone: great military leader, bad economist. Never made proper use of the tens of tons of English-made goods captured during the thousands of search-and-seizure operations. Never exploited the English know-how in his possession. No effort to reduce the costs of supplier diversification. No investments in import-substitution. No attention to the empire's peripheries.

French factories were initially ordered to increase the production but no talk about import substitution took place before the 1810s. When Napoleon changed his mind it was too late: the British had recovered from the blockade, partners and allies were receiving illegally tons of English goods, the continental system was falling apart.

The most ambitious import-substitution project involved indigo, coffee and sugar, but it led nowhere. The prospect of replacing Indian indigo with French-based plantations clashed with the lack of investments and the low output of the existing factories. In 1813 there were three indigo-processing factories in France which together produced 6,000 kilograms. The following year, two of them ceased operations. The same thing happened with sugar.

Ultimately, Napoleon made another severe and meaningless mistake, that is to supply England with foodstuffs. If there's something whose weaponization could have brought the British on the brink of collapse that was precisely the food. Indeed, the UK had an issue in terms of food security – as shown by the episodic food shortages which took place between 1795 and 1812 – and France could – and should – have used such a vulnerability to starve out the rival, forcing it to bargain. The question is: is gas Russia's the equivalent to Napoleon's food?

The UK was particularly worried about the import of European-made corn, but eventually no embargo was ever declared upon it. Conversely, throughout the blockade period, France increased the exports to the UK of cereal products like corn, wheat and grain, in accordance with a merchantilist-inspired food-for-metals policy.

Conclusions

The United Kingdom was heavily dependent on trade with the European mainland and vice versa. The former imported foodstuffs and the latter imported colonial and manufactured goods. The blockade should have equally harmed both of them but it ended up catalysing France's falldown and fostering the British post-Napoleonic economic miracle. Last but not least, London's strategy based on circumvention, distraction and diversification set the ground for the global expansion of the British empire and for the rise of the modern-way Commonwealth.

The British counteroffensive to Napoleon's economic war needs to be re-discovered and to be read for what it is: a source of evergreen lessons on economics and strategy. Of the several lessons that can be drown from this historical episode, three stand out for importance and topicality:

The British resorted at the same time, and with the same vigor, to smuggling and to unconventional guerrilla operations so as to distract Napoleon and to deprive him of resources. Between 1808 and 1810 the British government funded uprisings and insurgencies all over the Old Continent, spending about £32,000,000. These operations proved fundamental in destabilizing the Continental System from within and worked in parallel but complementarily with smuggling. Explained otherwise: economic wars are more about war than economy; indeed, they can be won by playing smarter.

It's fundamental that a major power avoid falling into the great-state autism trap. Discontent can be easily exploited by an artful rival. Spheres of influence can last and withstand external pressures only if metropolis and peripheries are tied by trust-based win-win relations.

The British dealt with the sudden lack of foreign-made goods by increasing the domestic production but at no time the goal was to close themselves from the outer world. The disposal of more goods made it possible to satisfy the illegal demand both from Europe and new markets. It's the self-proving evidence that economic wars can be at the same time a life-threatening challenge and an unrepeatable opportunity – everything depends on the target's reaction. The British found salvation between the Americas and today's Commonwealth, Russia might find it outside the West.

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.