2017 is neither 1917 nor 1989. What Trump and May signify is a circulation of political elites. The ascending elites represent a national bourgeoisie, the descending ones, cosmopolitan global interests. The most likely outcomes are a shift in public policy to greater regulation legitimated by economic nationalism, the decline of regional blocs, an increase in bilateral trade agreements, and a more cost effective foreign policy.

The year 1917 was the overture to a century of socialism which ended in 1989. Does the election of Donald Trump and, following the UK’s exit from the European Union, Theresa May, herald a new turning point in international politics? Trump, more strongly than May, holds a world view which promises a challenge to the complacent Western political elites who have ruled on the basis of neo-liberal politics for the past twenty years.

Populist Appeal

Donald Trump came to power to the surprise of the world’s political classes. In his inaugural speech he declared: ‘For too long, a small group in our nation's capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost. Washington flourished, but the people did not share in its wealth. Politicians prospered, but the jobs left and the factories closed. The establishment protected itself, but not the citizens of our country. … And while they celebrated in our nation's capital, there was little to celebrate for struggling families all across our land….:mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities, rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape… This American carnage stops right here and stops right now’.

Theresa May’s rise to state political leadership was no less surprising. The UK’s membership of the European Union, which had been part of the international political architecture since the formation of the European Economic Commission in1957, was rejected by a referendum of the British electorate. May, the previous Conservative Home Secretary was elected Prime Minister by her Party consequent on her predecessor’s failure to secure a positive British vote on membership of the European Union. In Birmingham on 5 October 2016, in her first speech as Conservative Prime Minister, she echoed many of Trump’s sentiments. ‘…. [C]change has got to come …. because of the quiet revolution that took place in our country just three months ago – a revolution in which millions of our fellow citizens stood up and said they were not prepared to be ignored anymore. It was about a sense – deep, profound and let’s face it often justified – that many people have today that the world works well for a privileged few, but not for them. ..

[T]oo many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ … People with assets have got richer. People without them have suffered. People with mortgages have found their debts cheaper. People with savings have found themselves poorer.’

While both leaders are yet to define their positions, already a number of policy positions are beginning to surface.

From Globalisation to Internationalism

First, the borders of countries will become far less porous. Internationalisation – processes which allow controls over borders, will replace globalisation – networks which occur independently of borders. A major rebalancing will take the form of moving from multilateral to bilateral agreements and trade models. Countries will become decoupled from regions. The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), if it continues, will do so without the USA and will strengthen China’s position in the Pacific. NAFTA will be weakened. The European Union will continue on a downward spiral. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, with its more informal structures enabling bilateral agreements, is a likely template for regional organisation rather than the legalistic and treaty-based European Union. The political leadership of states seeks to strengthen political power at the expense of regional economic and political blocs. There will be more protectionist tariff policies against the free movement of goods and capital.

Strengthening the Nation State

Second, the neo-liberal assumptions of free movement of labour, capital, services and goods will be replaced by a state led policy with a greater stress on industry and job creation. Core countries like the USA and the UK will seek to recover their manufacturing base as well as promoting new high-tech industries. The intentions are to modify the power of market exchange and institute Keynesian policies of state intervention to revitalise and replace dying industries and decaying regions.

Both leaders appeal to a similar social base. The new American and British political elites will look to political support from the dispossessed working and middle classes and small business. And both recognise, though in different ways, that corporations have to serve communities as well as shareholders. As Theresa May put it in a speech of 27 January, ‘We will put the interest of working people right up there, centre stage’. There will be greater government control of cross border movement of capital and labour. Policy will involve more scrutiny of foreign acquisitions and mergers. In the UK, corporate governance could strengthen stakeholders to oversee reductions in differentials between executives and employees. For May and Trump, a shift of wealth is promised from London and Washington DC respectively to the regions. These are the intentions and all will face significant difficulties in implementation. Immigration will be subject to more stringent control: for the UK from the remaining 27 countries of the EU and for the USA to people who could be considered to constitute a terrorist threat. These are the policies which receive political electoral support.

Towards a Pluralistic World System

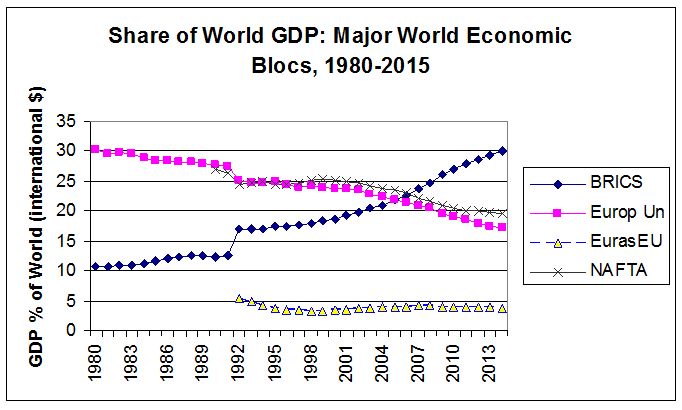

Third, ‘making America great again’ can only occur in a world which acknowledges the rise of China as a major power and the relative economic decline of the USA and European Union. Both the European Union and NAFTA trading blocs have in recent years experienced significant falls in their ‘market share’ of world GDP. As we note from Figure 1, the portion of the EU has fallen from 30 per cent of world GDP in 1980 to 18 per cent in 2015 and that of the BRICS has risen from 11 per cent to 30 per cent in the same time period. This is the material base which gives China its economic and growing political power. The Eurasian Economic Union contains underperforming economic and political powers.

Figure 1. Proportion of world GDP 1980-2015: BRICS, European Union, Eurasian Economic Union and NAFTA. Purchasing power parity (Current international dollars).

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base, 2015.

In this context what is required is not just the reinvention of the ‘dual burden’ of the USA-UK ‘special relationship’ but a wider international political reappraisal. Trump has avoided the demonising of President Putin, and further recognition of Russia’s active diplomacy in the Middle East might well lead to a more realistic and less interventionalist policy on the part of the USA. Despite his earlier statement that ‘NATO is obsolete’, in response to Theresa May, he has affirmed his backing for it. Questions remain, however, on whether it should continue in its present form and whether the USA is willing to finance European and Middle Eastern internal wars. Trump questions whether NATO is cost effective for America’s interests. Unlike the British Labour Party Leader, Jeremy Corbyn, the British establishment pursues a strong anti-Russian policy based on the NATO alliance. With the decline of neo-liberalism as a policy guide to the destiny of human history, it is probable that democracy promotion on the part of the USA will be replaced by an ‘America First’ policy. This need not weaker commitment to NATO but it might lead to greater caution and less involvement in foreign wars.

Opposition

It is clear that Trump is strongly opposed by the established political classes. He is widely considered a demagogue. In the London Observer he is demonised: he ‘is ignorant, prejudiced and vicious in a way that no American leader has been’ (29 January 2017). Whether he succeeds will depend on the success of his domestic policy of job creation and improvements in economic well-being. The foreign affairs elites may care about his standpoint to Russia but this does not impinge on domestic political constituencies. Hence despite media criticism he can adopt a new strategy to Russia without incurring damaging political costs. If his protectionist economic nationalism continues, corporations who have gained from globalisation will have to consider how far they can adapt to protectionist policies by relocating their supply chains to the USA. Theresa May will be faced with different issue of keeping the financial sector in the City of London.

While significant sections of the electorate in both the USA and the UK are currently captivated by populist policies, it remains to be seen whether state political leaders are still powerful enough to defeat corporate business and a hostile mass media. Governments have the power to impose punitive tariffs on imports and award generous tax incentives to exporters. But there are limits – both constitutionally and economically.

2017 is neither 1917 nor 1989. What Trump and May signify is a circulation of political elites. The ascending elites represent a national bourgeoisie, the descending ones, cosmopolitan global interests. The most likely outcomes are a shift in public policy to greater regulation legitimated by economic nationalism, the decline of regional blocs, an increase in bilateral trade agreements, and a more cost effective foreign policy.