The economic blockade and the war against Syria, as well as the coronavirus pandemic, have had profound consequences, and their impact will continue for many years, writes Ali al-Ahmed, Syrian politician and public figure, for valdaiclub.com.

The coronavirus pandemic significantly complicated the life of the Syrian people amid an on-going war which has already lasted almost ten years, affecting all areas of Syrian life, including security, economics, education and healthcare.

Healthcare goals are not achieved because of the poor working conditions and underdevelopment of the sector, which continues to lack the requisite infrastructure, human resources, medicine and work standards. The results of the healthcare system depend mainly on ensuring the proper conditions and environment; they are closely related to the health of the economy and the educational life of the population, as well as its knowledge and cultural capabilities. All of these aspects of otherwise normal civilian life in Syria have been directly affected by the war, an unrelenting siege that affects all Syrian citizens, all institutions, and all spheres of social and political activity, with no exceptions. The United States punishes everyone for the desire to live in their own homes and be happy for their country.

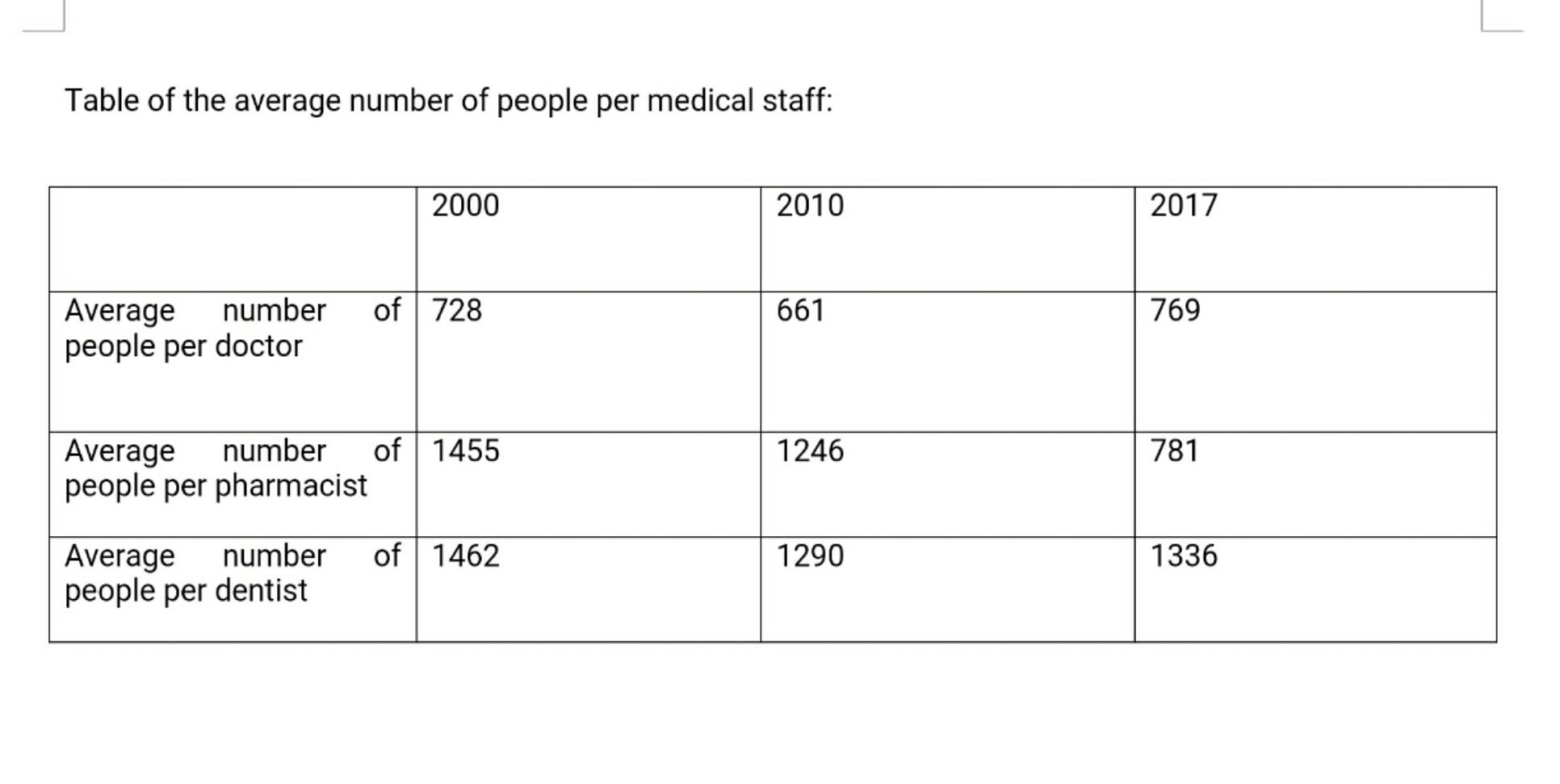

Before the war, the healthcare system can be characterized by the following data: the number of hospital beds per capita improved, from 830 people per bed in 2000 to 648 people per bed in 2010. The number of hospitals per person improved from 16,602 people per hospital to 13,691 people per hospital over the same time period. This improvement is associated with an increase in the number of hospitals from 390 to 493, of which 113 are state-owned and the rest are private. The number of medical centres increased from 983 to 1,506 between 2000 and 2010.

In some provinces, there was an acceptable ratio between people, beds and hospitals. The number of people per bed in the provinces of Latakia, Tartus, As-Suwayda and Damascus remained at 512, 609, 553 and 745, respectively, in 2000 and 2010, while the same figure in the provinces of Idlib, Al-Hassakah and Raqqa improved between 2000 and 2010 to 1,301, 1,105 and 1,148 people per bed, respectively. Another difference was observed in the average number of people per hospital: in the provinces of As-Suwayda, Tartus, Latakia and Homs, the average number was 3,719, 4,950, 8,325 and 8,142 people per hospital, respectively; this average improved in the provinces of Aleppo, Al-Hassakah and Rif Damashq to 17,933, 16,250 and 13,544, respectively.

The war in Syria has wreaked havoc on the healthcare sector, severely damaging the infrastructure of all economic and social sectors. About 29% of all hospitals were completely or partially destroyed. The efficiency of those hospitals that managed to avoid destruction was reduced by half, mainly not because of the lack of professional personnel as a result of emigration from Syria, but because of the acute shortage of working medical equipment. Hospitals and medical centres cannot provide the proper level of service for such equipment due to the blockade and due to manufacturing companies that service various institutions of the Syrian state being banned from operating in Syria, including those related to health and nutrition.

As of 2014, the ratio of the number of nursing staff (including obstetrics staff) per person in Syria had reached 1.98 employees per 1,000 people, which is significantly lower than the average announced by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), of 9.1 employees (without obstetrics staff) per 1,000 people

The organisation Doctors for Human Rights estimated the number of doctors who left the country before the end of 2015 to be 15,000, which is 50% of the total number of doctors (about 30,000) registered in Syria in 2009. This is a lot. Such losses, which benefit the countries to which the doctors have emigrated, cost the Syrian state billions, and have had an extremely negative impact on the entire Syrian health sector.

Before the war, Syria had posted good results in the field of food security thanks to extensive irrigation programmes, an increase in the amount of cultivated land, expanded land reclamation programmes, and also thanks to other measures taken in the field of agriculture. The first national sustainable development report mentioned progress made in reducing the proportion of the population which faced difficulties obtaining food; this figure fell from 2.2% in 1997 to 1.1% in 2010. One of the new means of totalling the extreme degree of poverty that has resulted from the war is the measurement of indicators and levels of food security for Syrian families, indicating the extremely negative impact of the war on relevant food conditions. This is confirmed by the report on family food security, according to which about a third of Syrians (33.4%), are already at risk. To this indicator we add a little more than half (51.6%) of Syrians who are at risk of losing some food security, which means that only 15.6% of Syrians are safe in terms of food provision.

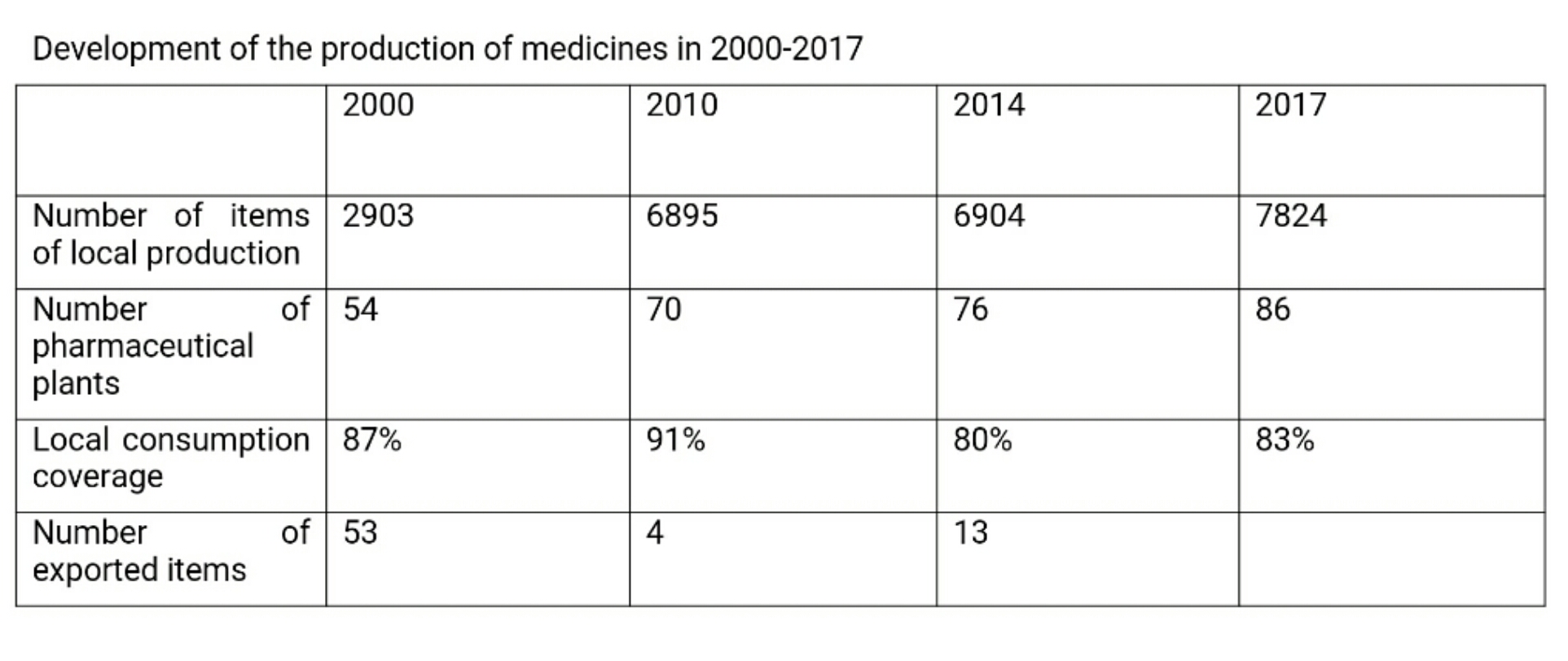

The following figures show the development of the production of medicines in 2000-2017:

Source: Statistical Groups 2001-2018, Central Bureau of Statistics.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the economic blockade and the war against Syria, as well as the coronavirus pandemic, have had profound consequences, and their impact will continue for many years. These consequences will not be limited to the territory of Syria, their influence will extend to the neighbouring countries of the region and beyond, including Europe, since Syria is united with it by the Mediterranean. The example of a coronavirus pandemic, which has freely penetrated all borders, shows that it is impossible to isolate such crises. This crisis should unite the world and encourage wise people in every country to influence the authorities so that they stop politicising human relations and don’t raise their hands against people, which, in their opinion, justifies the violation of international law.