The G20 summit held in Osaka in late June 2019 was marked by a small revolution. The traditional phrase on the benefits of multilateralism has been omitted from the final communiqué. This is an important change, which seems to have been overshadowed by the commentators. But, this change was not the only one. It seems that we are heading for a new world, one dominated by the return of the nation-state.

It has been quite clear that since the election of Donald Trump in 2016 many things have changed, even if he is not the only person, nor even perhaps the principal one, responsible. It has obviously shaken the coconut tree a lot: from the brutal renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Mexico and Canada, to the trade dispute with China, or the one that is forthcoming coming with Germany, with the cancellation of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

But these commercial conflicts and their consequences only confirm the failure of a global mode of governance. What is called multilateralism is about to die, and the agreements signed in haste like the agreement between the European Union and Vietnam or the agreement between the EU and MERCOSUR (the Latin American trade bloc shared by Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay) are actually the tail of the comet. The return of nation-states as driving forces of international relations is essential. So, even if we will continue to trade with each other (there is no question of a return to autarchy) it is the end of a form of globalisation that we are witnessing today.

This return of nations as the main actors in international trade is also raising the issue of currencies. If the US dollar is now contested as the world’s reserve currency, it remains to be seen what could serve as its successor, and even if there could be any.

The end of a form of globalisation?

Events heralding an end to this kind of globalisation have been spread out over a long enough period, even if we only realize it today. This is true of the paralysis that has plagued the WTO and the "Doha Round" of trade tracks since the beginning of the 2010s. Other such events have occurred over a shorter period of time. It must be noted that the period from 2016 to 2018 was particularly fertile in terms of these sorts of events. Of course, we had the Brexit vote in the UK, which has resulted in a major shake-up among the companies of the European Union. Donald Trump has, meanwhile, ended the free trade agreements discussed for several years, such as TTIP, and renegotiated the treaty with Canada and Mexico (NAFTA). He then began a showdown with China, probably ahead of plans to do the same with Germany within the next several months.

It should be recalled that the trade war between China and the United States began in January 2018, when Donald Trump set up “over four years” of customs duties on washing machines and solar panels produced in China. In retaliation, in February 2018, China triggered an anti-dumping investigation into US sorghum, accusing the United States of subsidizing its cultivation. On March 8, 2018, Donald Trump signed a decree introducing a 25% tariff on aluminium imports and a 10% tariff on steel imports, targeting China in particular. Then, the clash moved to high-tech goods. Huawei, the Chinese electronic giant, became the victim of Donald Trump’s wrath and following the breakdown of negotiations, China announced in June the introduction of new customs duties on $60 billion in imports from United States. These various measures have destabilised financial markets.

It is clear, however, that an agreement will have to be found. Both countries have a lot to lose in a clash, and both Presidents have, for different reasons, a need for an agreement. However, this agreement will not be that commercial. It will also encompass the geostrategic issues on which the two countries are confronting each other. And, if some sort of agreement is signed by the end of 2019, it would probably be a stopgap solution.

The reversal of the balance of forces between the United States and China

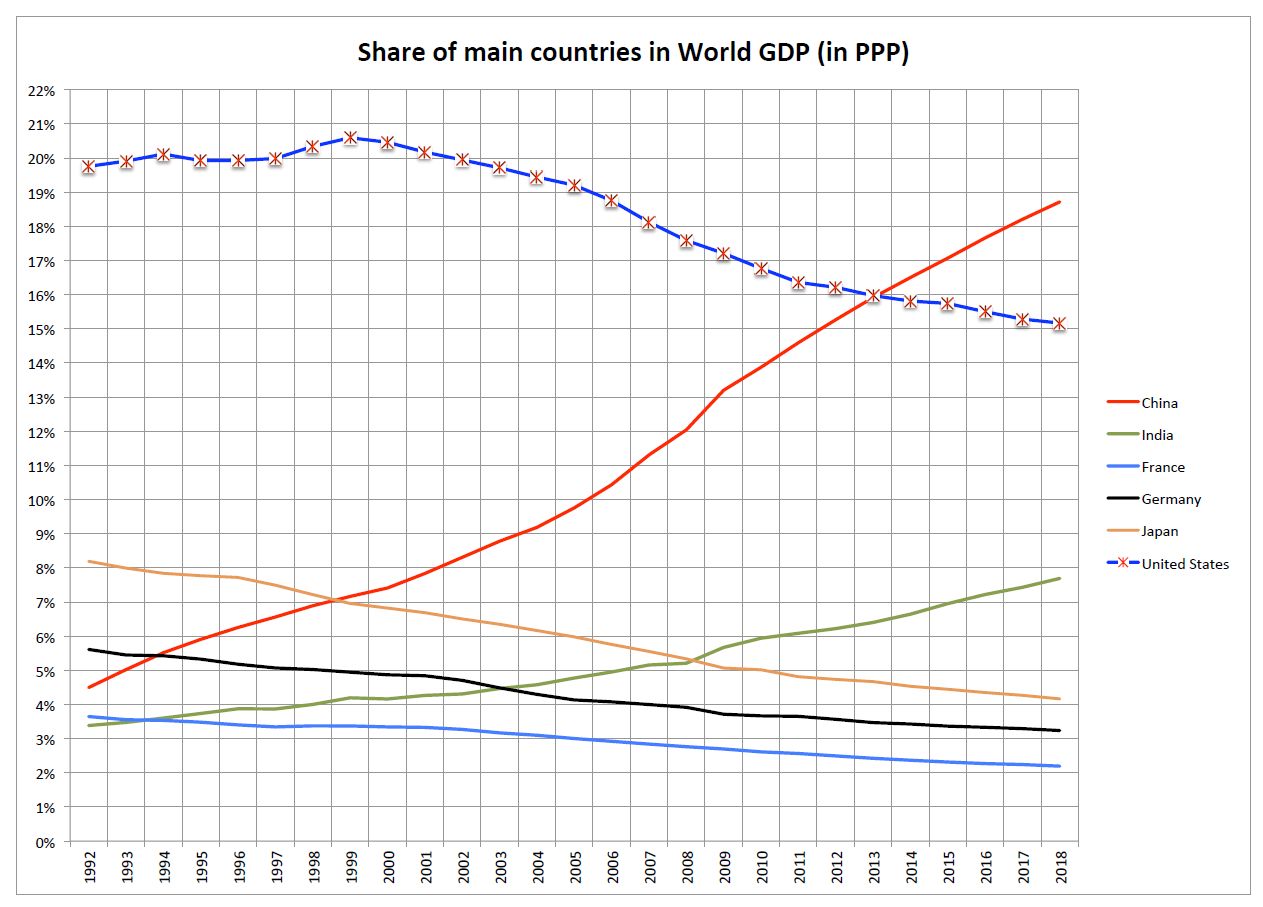

But this standoff between the United States and China only conceals an inversion of the balance of power. If we look at world GDP, calculated in purchasing power parity to erase the erratic variations of currencies, we see that China overtook the United States in 2013. The US is no longer the largest economic power in the world, a major change if we look at the dominant players in the global scene since 1919. This change took probably place by 2013-2015. We are seeing, in fact, the end of the “American Century”, even if this name applies more precisely to the era which lasted from the end of WWII until the beginning of the 21st century.

Graph 1

Source : FMI

This inversion is not the only important phenomenon. Indeed, we also see that India has overtaken and Germany and Japan. The rise of this country, which now accounts for 7.8% of global GDP, more than Germany and France combined, is undeniable too. It marks the progressive turn from an Atlantic Ocean-centred world economy to a Pacific Ocean one. In short, what is becoming obvious is that we are witnessing a shift in the balance of power on a global scale. China and India account for more than a quarter of world production, exactly 26.5%.

The agony of the G7 and the rise of the G20

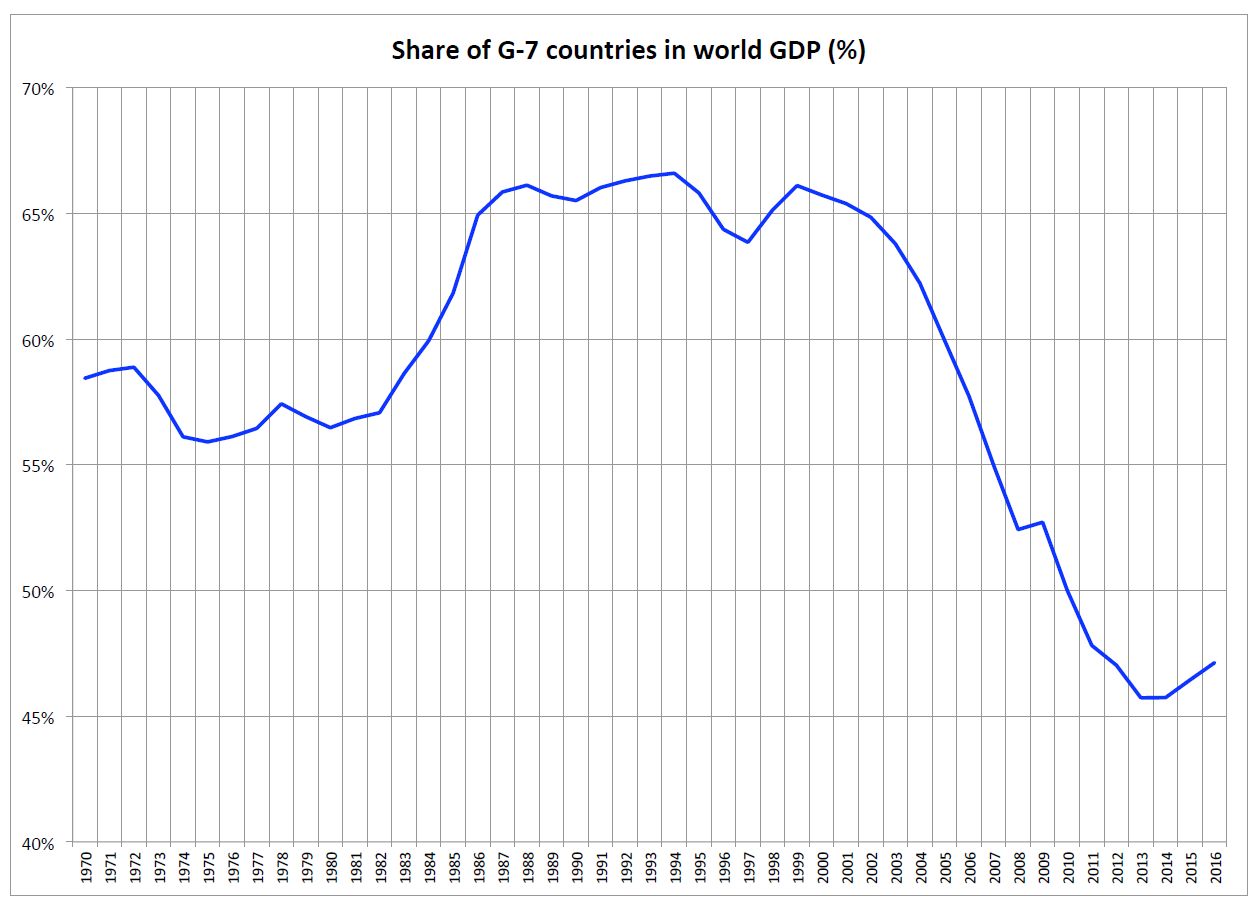

Under these conditions, the old institutions are becoming largely obsolete. The G7 will meet in late August 2019 in Biarritz, France. However these Western countries plus Japan, which first met in the early 1970s to regulate the movement of currencies, is no longer the centre of attention, because its economic weight is now declining. It lost its legitimacy with the expulsion of Russia in 2014, a measure against which Japan had wisely protested at the time. The G7 has become a politicized forum, a group of US-allied countries. Even more importantly, the G7 is losing its economic supremacy.

Graph 2

Source : FMI

In 2000, the G7 accounted for two-thirds of global production. In 2017, its relative weight is only 48%. Here we measure its loss of power, a loss that should accelerate in the years to come. This is even truer if we look at investment in G7 countries compared to world investment. While one country still maintains a high share of investment (Japan), all the others are witnessing a declining trend. This is particularly important because today’s investments are tomorrow growth and production.

From now on, the economic fate of the world (and sometimes its overall fate) will be played out in the G20. We have emerged from the midst of the great Western countries, whether we like it or not.

The end of mercantilism

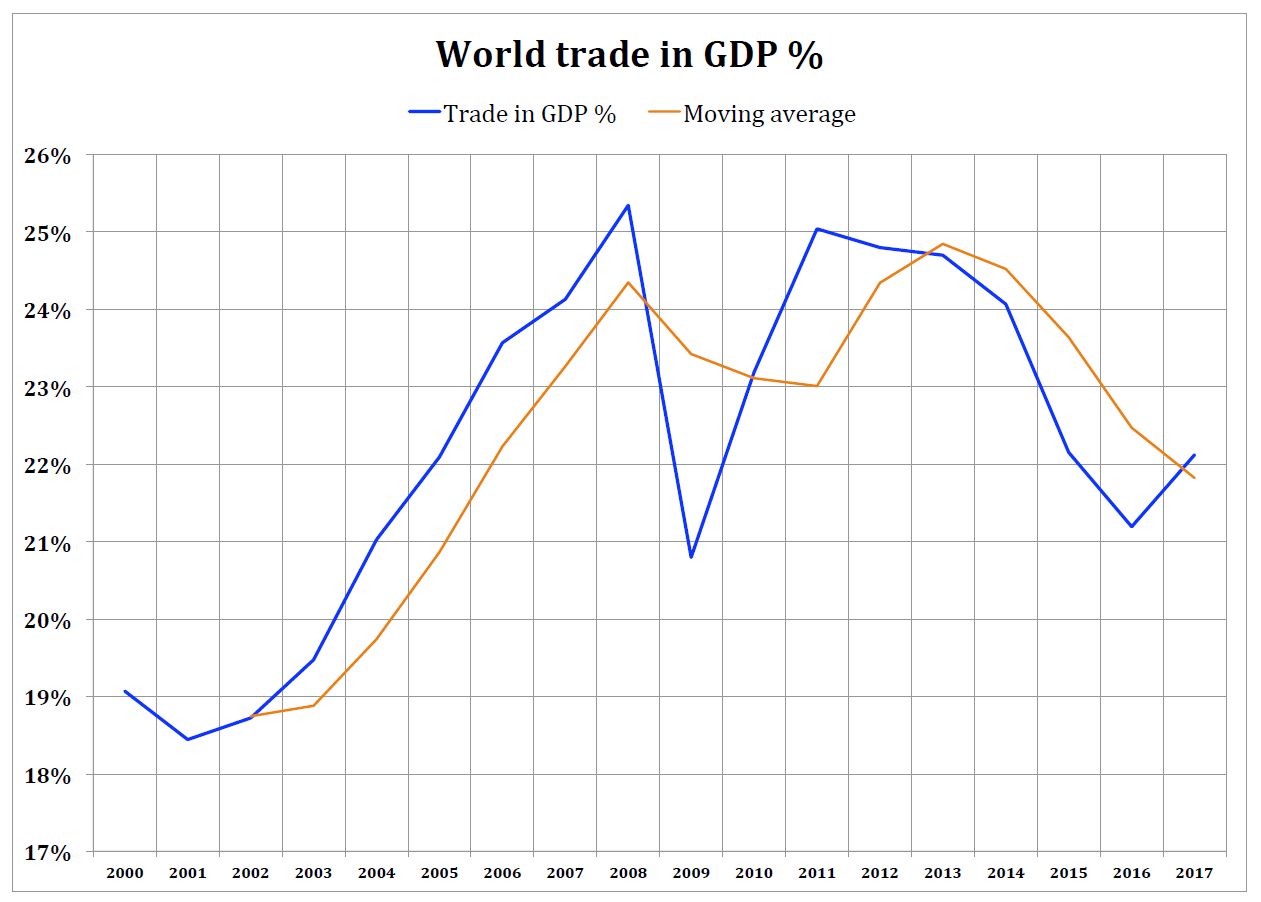

The crisis of globalisation is also measured differently. We can see that the share of international trade in world GDP, which had been rising until the crisis of 2008, is now declining. This slowdown dates back several years. It is another major a change, one that could be called paradigmatic. Of course, this change is just a return to sanity. Trade doesn’t create production. It’s production that could create trade. Of course, trade enhances competition. But competition could also be destructive as far as production is concerned. It reflects the fact that some of the major exporters have changed their strategy, such as China and other countries focused on their domestic markets. It’s a paradigm shift we are witnessing.

This is a general evolution. It is also reflected in France with the progress of “Made in France”; the promotion that Arnault Montebourg had launched a few years ago. Of course, this movement is slower for the EU countries, which remain strongly infatuated with the ideology of “happy globalisation”. This is particularly the case for Germany, which continues its mercantilist strategy based on the exploitation of other economies, a strategy that puts it in direct conflict with the United States. But the trend is general.

Graph 3

Source : FMI

Its relevance is certainly important. Excesses of free-trade have introduced severe imbalances to the populations of each country. The current appeal of “populist” movements emerges from these imbalances, and is also the reason behind the election of some world leaders, like President Trump and Prime Minister Modi. The necessity to fix the situation implies a kind of return to protectionism.

Is there a currency war in the making?

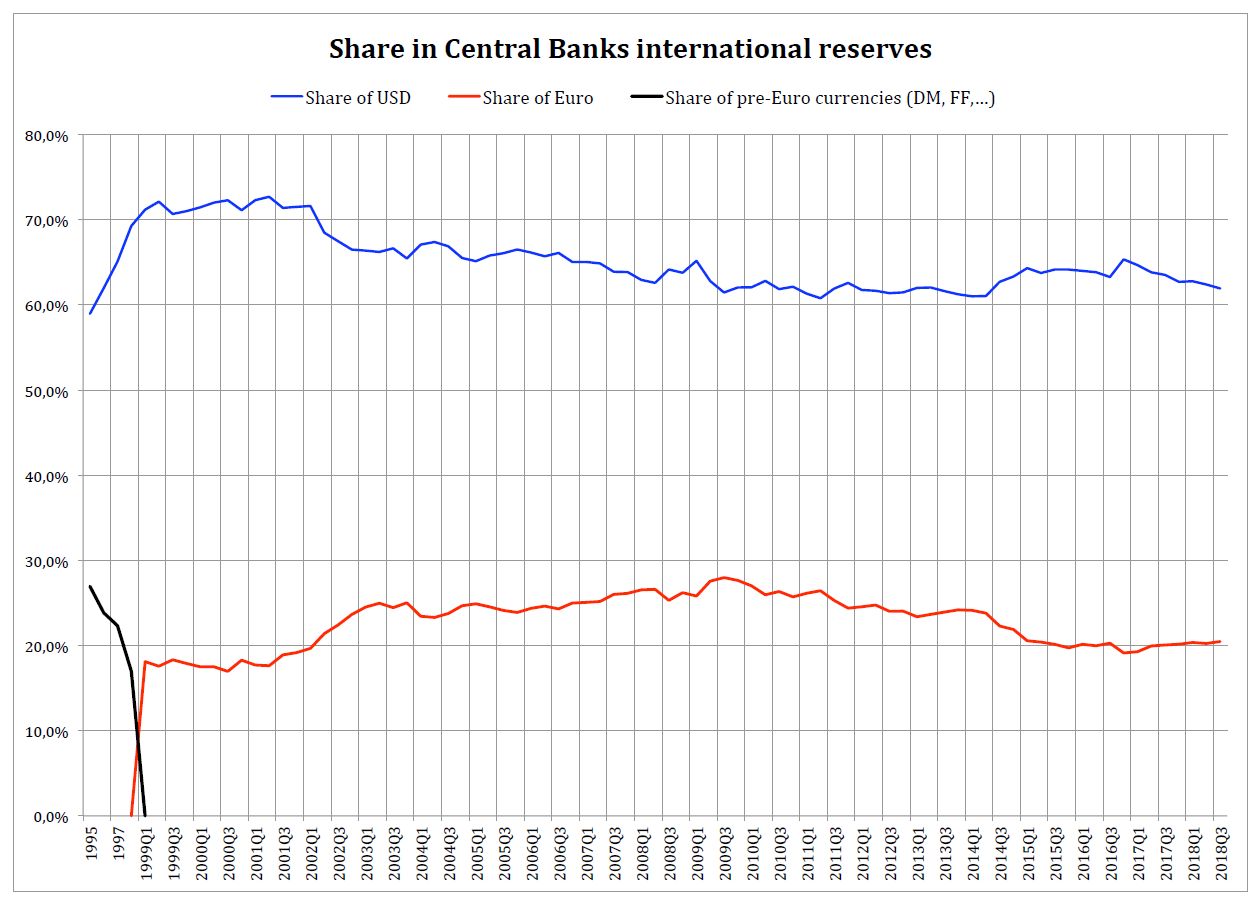

The return of the nation-states as major actors of international trade raises the question of the purchasing power of currencies. Donald Trump recently re-addressed this issue. For him, the euro allows for a massive under-evaluation of the value of German exports, a fact which has been confirmed by many IMF studies. The international role of the US dollar itself is now disputed, in particular because of the political use that the United States has made of it for several years. Also, overall, we are witnessing a decline in the dollar's share in the share in the foreign exchange reserves of central banks.

The so-called “de-dollarization” of trade presents new questions here, even if it is proceeding more slowly than some had hoped. Actually, for the last two years (from the last quarter of 2016 to Q4 2018) the RMB’s share in central bank reserves grew at more than 7.8% of the incremental increase. It is then quite possible that its weight would reach 5 of the global stock in 2022/2023. Second, it is important to consider that the RMB’s share in investment is above the euro level. It is then clear that the RMB is developing quickly as an international currency, be it for central bank reserves or financial transactions, however, we are just at the beginning of this process and the RMB is still not free of all its previous limitations.

As logical as it is, it could encounter political problems if relations with the USA worsen, or economic ones if the US dollar begins to fluctuate wildly because of Trump’s policies. Another issue would be the consequences of the possible introduction of a “Chinese SWIFT” system or, more precisely, a common system developed by Russia and China known as SPFS/PSSA competing with the US dominated SWIFT. It would then imply a sharp increase in the RMB share. However, it would also increase dependence on China. Would China be more predictable than the US? This is quite possible. Would other governments be happy with swapping a dependency on the USD with dependency on the RMB? This is something to be seen.

Clearly, the pivotal currency for the world monetary system would be linked to the pivotal country in the global economy. This country can’t be the US. They have been overtaken by China, if we look at the PPP GDP since 2013. They still are influence but they can’t be dominant. Would China assume this new global responsibility? The answer here is not obvious. But, what can be said is that the European Union is not to be major a player in the coming world. Its internal divisions, and even oppositions, are much too strong. The EU will still be an important trade zone but will be less and less significant as a currency union.

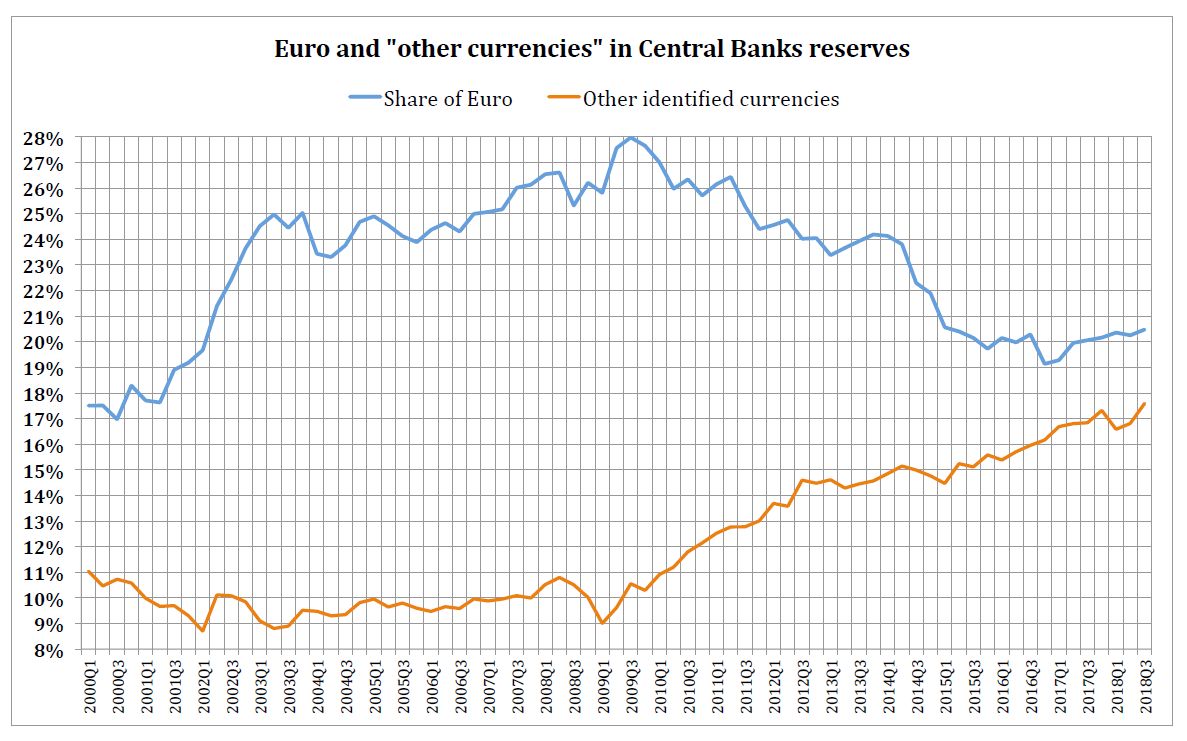

This decline of the dollar in the reserves of central banks isn’t the result of the introduction of the euro. It certainly experienced a phase of expansion, from 1999 to 2008, when it went from 19% to 28%. But since 2010, its share has ebbed. It’s even fallen below the share held by the currencies that made up the euro before 1999. This share has now fallen to 20% of the world’s reserves. The other currencies, the yen, the British Pound and the Yuan, have benefited from the decline of both the USD and the euro. This point is important in itself. We are entering a situation of monetary multi-polarity, just as we’ve entered a situation of economic and political multi-polarity.

Graph 4

(Source FMI)

Graph 5

Source : FMI

We have, then, to face actual facts. Dreams of global governance have collapsed. We are witnessing the return of the nation-states and this is true de-globalisation. The G20 meeting held in late June in Osaka has, in fact, endorsed this situation.

The challenge today is to develop the rules of international cooperation that exist between these nations, to jettison the reasoning that leads us to shout “Europe, Europe” like goats, to take an interest in this vast world and to forge the alliances we will need tomorrow.