To some policymakers and analysts, if WTO rules get in the way of tackling the pressing threat to humanity then these rules will need to be pared back. To others policies to tackle climate change and to facilitate the associated transition towards renewable energies are a Trojan Horse for the next wave of protectionism. Both perspectives could result in governments reassessing the balance of benefits from their membership of the WTO and their willingness to undertake further cooperation there, writes Simon J. Evenett, Professor of International Trade and Economic Development, University of St. Gallen.

The 21st century has not been kind to the WTO or, more precisely, to the rules-based multilateral trading regime negotiated in 1993. In this column, based on the introduction of a recent eBook co-edited by Richard Baldwin and myself, I highlight three underlying forces reshaping global trade governance. While the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout naturally receive much attention, it is these three forces that have created fundamental problems for those governments seeking to solve trade problems in Geneva.

Three symptoms of the malaise

There are three symptoms are the WTO’s current malaise. First, some WTO members have re-evaluated their approach to engagement with trading partners, calling into question the general presumption towards more engagement and openness.

Second, the painful negotiations over the Doha Development Agenda made plain that trust between WTO members—a sufficient level of which is necessary in a system where compliance is in large part voluntary—has diminished over time.

A third symptom is the growing sense that the current trading arrangements are unbalanced. The notion of balance has been outlined by Deputy Director-General Wolff as follows:

“Balance in the world trading system, as seen through the eyes of any WTO Member, is provided in a variety of ways:

-

Through the Member’s judgment of the costs and benefits of the rights it enjoys and the obligations it has undertaken;

-

Through its view of how its costs and benefits compare with those of other Members,

-

Through a Member’s view of its freedom of action in relation to the freedom of action for others and specifically through its judgment of whether it has sufficient freedom to act to temper its commitments for trade liberalization (openness) with measures designed to deal with any harms thereby caused” (Wolff 2020).

This definition is useful as it provides a lens through which to view the consequences for the standing of current multilateral trade rules of the systemic shocks witnessed over the past 15 years, of the broad shifts seen in the global economy, and of the shackles of the Uruguay Round. The first notion of balance relates to absolute benefits, the second to relative benefits, and the third to freedom of manoeuvre in response to unforeseen events.

Causes and consequences of imbalance

At least three longstanding and increasingly inter-related trends bear upon the perceived balance of obligations and benefits from WTO membership:

-

sustained faster economic growth in the emerging markets,

-

technological developments resulting in the expansion of the digital economy, and

-

climate change and the associated energy transition.

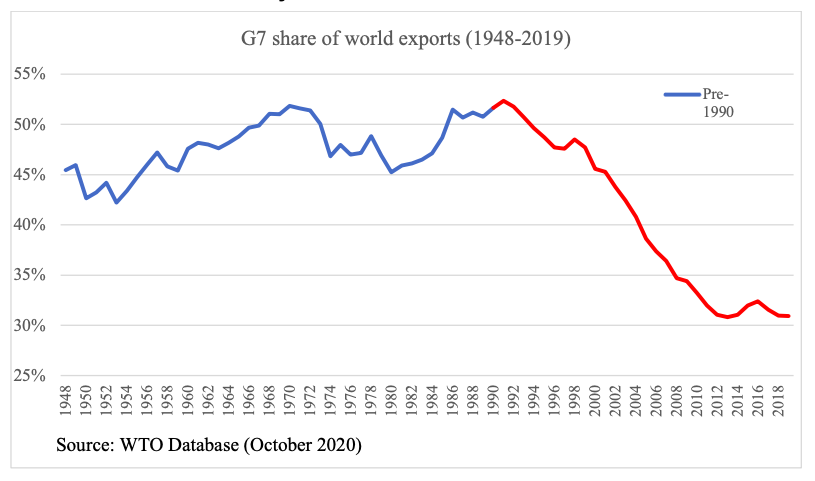

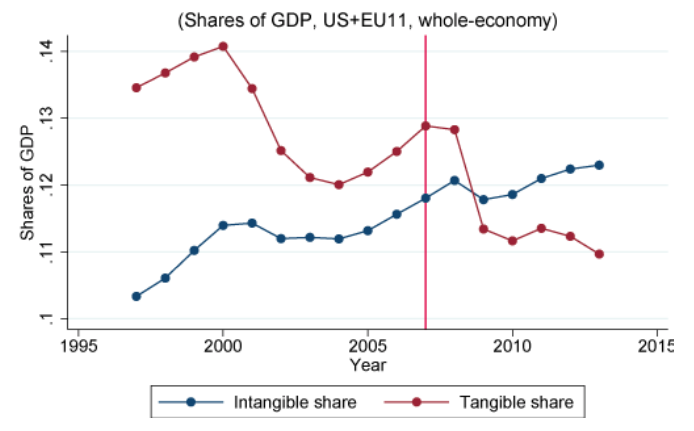

Figure 1: Since the late 1980s, the G7 group’s shares of world GDP and world trade have shrunk markedly.

The first trend has resulted in a growing share of global GDP and commerce accounted for by emerging markets and diminished relative economic importance of the Group of Seven industrialised countries, whose members had essentially dominated the world trading system through to the end of the Uruguay Round (see Figure 1). In line with their growing economic heft, the governments of the larger emerging market economies—Brazil, China, India, and South Africa in particular—have asserted themselves more forcefully in the run up to and since the launch of the Doha Round of multilateral trade talks in 2001, as is their right.

Seen in terms Wolff’s three notions of balance, from the perspective of some Western powers the impression arose that, while they still benefit in absolute terms from WTO membership, their benefits relative to emerging markets have declined. To the extent that more intense import competition has resulted in painful labour market adjustments in both industrialised and developing countries, then the political calculus may have shifted towards lower perceived absolute and relative benefits of WTO membership.

These shifts in relative benefits have not been matched by corresponding increases in obligations taken on by developing countries—leaving some policymakers and analysts in industrialised countries to call for a rebalancing of rights and commitments at the WTO (Low, Mamdouh, and Rogerson 2019).

For their part, many developing country representatives insist that their multilateral trade obligations should reflect their nations’ level of development, implicitly arguing that this consideration should determine level of obligation rather than the scale of membership benefits. That such a rebalancing has not happened is said to have contributed to the United States essentially revoking MFN privileges for China in its trade war. Stalemates have consequences.

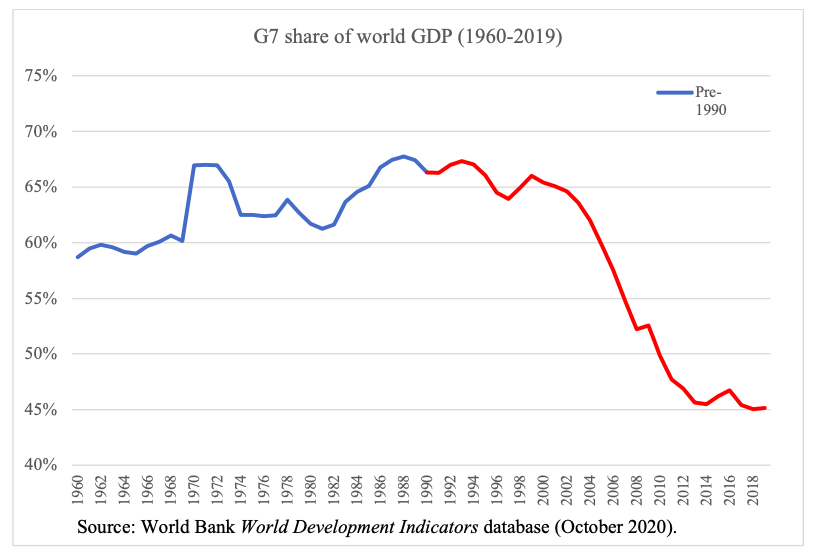

The spread of general purpose information and communication technologies and the subsequent development of the digital economy is the second trend that confronts the membership of the WTO. The rise in so-called digital commerce with its implications for disruption of traditional service providers, innovation, and relative economic performance have not escaped the attention of governments. Growth in private sector investment in intangible assets has exceeded that of national income in many industrialised countries (see Figure 2). Plus, unlike tangible assets, investment in intangibles weathered the global financial crisis well.

Figure 2: For over a decade, private sector investment in intangible assets has exceeded that of tangible assets.

Source: Haskel and Westlake (2017).

Regulatory actions, competition law enforcement steps, and taxation measures have been introduced by states that implicate firms operating in the digital economy. While these state acts may be informed by traditional WTO principles, there is no distinct body of multilateral trade rules to cover the digital economy. Nor is there any official tracking of policies affecting the digital economy. Coming on top of no progress in expanding and updating the WTO’s rulebook on service sectors, large swathes of economic activity now fall outside multilateral trade rules.

For governments whose economies are increasingly service sector-dominated, or where the leading edge in technological development is in the digital sector, the absence of WTO rules must surely diminish their own assessment of the value of WTO membership. To use Wolff’s trichotomy, own benefits shrink as the sectors better covered by WTO rules diminish in relative economic importance. Moreover, WTO rules afford little or no protection against actions taken by trading partners that implicate commercial interests in a nation’s digital sectors. In so far as the digital economy is concerned, the very relevance of the WTO is at stake.

Technological developments have fused with geopolitical rivalry to produce a heady brew of export bans, public procurement limits, restrictions on cross-border mergers and acquisitions, and a revival of industrial policies. Attendant to the recent tensions between China and the United States is the re-emergence of the trade and national security policy nexus. To the extent that governments brook no interference on matters deemed related to national security, then this must effectively encroach upon the domain of economic activity covered by the WTO rulebook (Aggarwal and Evenett 2013).

The past decade has seen senior policymakers give more and more attention to the threats posed by climate change and the steps that can be taken to limit them. The Paris Agreement negotiated in November and December 2015 was the high point in international cooperation in this regard. This first order societal matter implicates the world trading system in a number of ways, not least because of proposals to impose border tax adjustments on imports from nations imposing no, or insufficient, carbon taxes.

To some policymakers and analysts, if WTO rules get in the way of tackling this pressing threat to humanity then these rules will need to be pared back. To others policies to tackle climate change and to facilitate the associated transition towards renewable energies are a Trojan Horse for the next wave of protectionism. Both perspectives could result in governments reassessing the balance of benefits from their membership of the WTO and their willingness to undertake further cooperation there. Indeed, the latter may be conditional on the outcomes of climate change-related negotiations in other international fora.

No wonder the WTO is in trouble

On reflection, given these three trends it is no wonder that the organisational and legal arrangements created by governments in 1993 to govern international trade relations are under strain. The world has moved on but in key respects the WTO architecture has stood still (Baldwin 2012).

However, the gloom must not be overdone. As Baldwin and I highlight in our introduction, remarkable as it may seem, governments have not lost the knack of trade cooperation (as evidenced by the large number of regional trade agreements, bilateral investment treaties, inter-agency cooperation agreements and the like), nor have they given up on unilateral trade reforms. According to the Global Trade Alert, this year has seen over 600 commercial policy reforms implemented around the world (more than double the level witnessed by this time last year).

In addition to confidence building measures and a review of the efficacy of the WTO rule book in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, Baldwin and I call on governments to identify imperatives that are widely shared and that define what the WTO can achieve over the next decade. The three forces identified here plus the legacy of WTO informed the identification of eight imperatives, not all of which will be shared by every government.

The goal should be to identify a common denominator (or core) of imperatives to shape the future work programme of this vital international organisation. In the absence of a common denominator, governments and their WTO ambassadors will continue to talk past year other.