On January 1, Brent crude oil was trading above $66/bbl. Three months later, it had fallen by more than 60% from that level. A coronavirus-driven decline was followed by a collapse when the three-year old agreement between OPEC and Russia to cut production and raise prices broke down. Last Sunday, in a bid to save the international oil markets, US, Russia and Saudi Arabia struck an oil production cuts deal, but its results are yet to be seen.

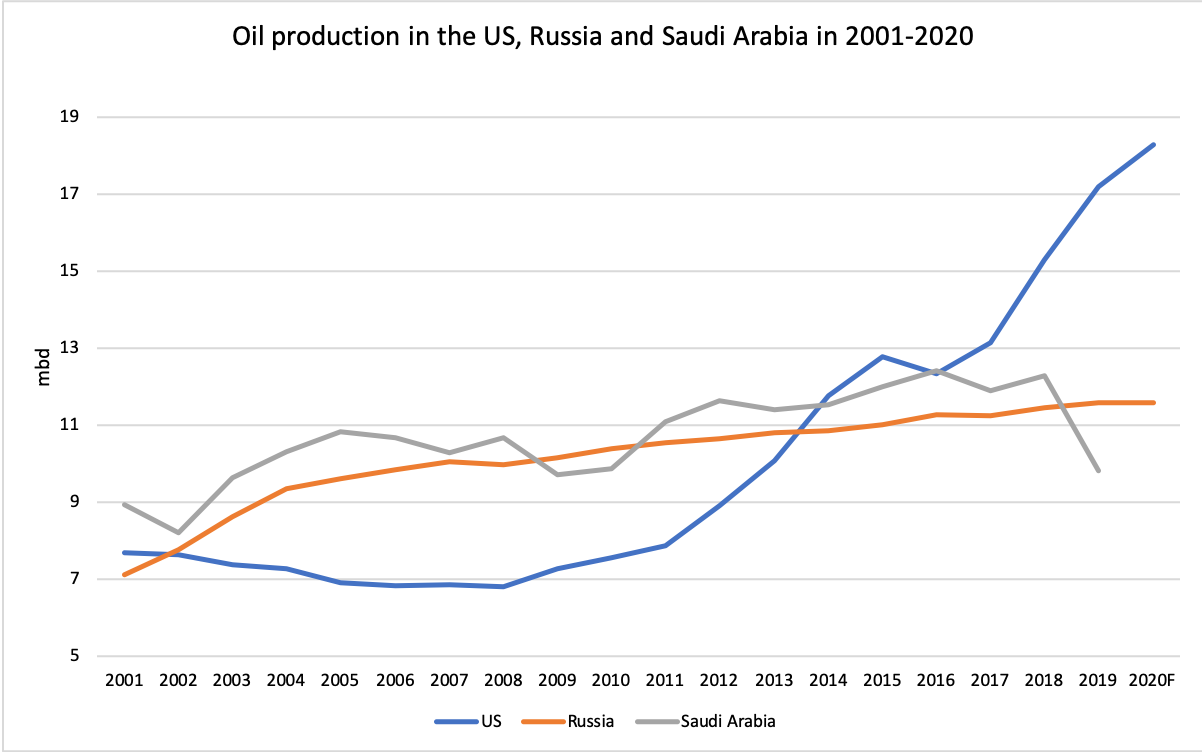

The root cause was a three-way tussle between Russia, Saudi Arabia and the US over market share in a shrinking global market for oil. The OPEC plus Russia (OPEC+) meeting in March aimed to reduce oil output, just as it had done in the past. This time, however, Russia was unwilling to support production cuts, noting that every barrel cut by OPEC+ just enabled the US to replace that barrel – leading to a net loss in revenue for those countries actually cutting their output.

The outcome resulted from Russia seeing an opportunity to challenge the US shale industry – a highly capital intensive, highly leveraged sector with weak cashflows – in an attempt to shut much of it down, eliminating the threat it posed to its own production. That left Saudi Arabia exposed and it, along with its Gulf allies, were unwilling to go it alone on production cuts, a policy tried and failed in the past. Oil prices reacted predictably – falling sharply in the days after the meeting in Vienna.

Where do we go from here? The answer is both fundamental and political.

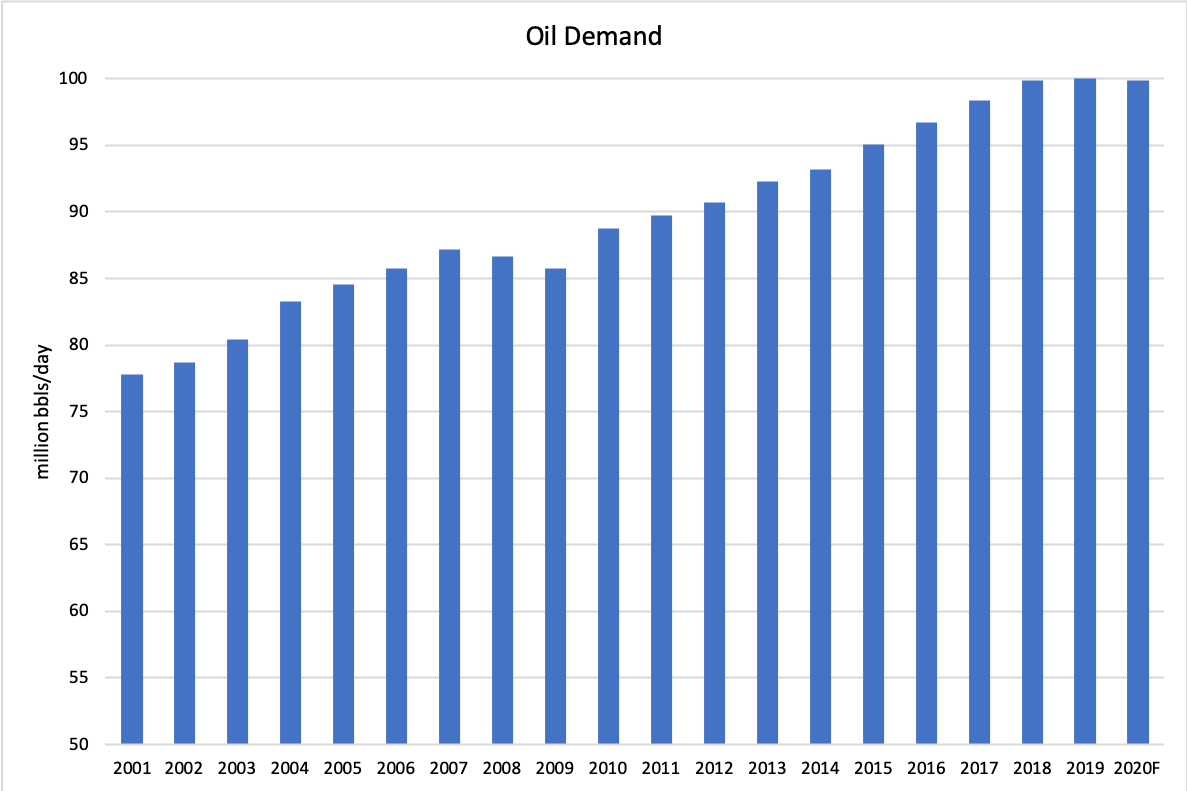

The scale and speed of the demand destruction from the coronavirus created the conditions both for Russia’s challenge to the US shale industry and Saudi Arabia’s response to that challenge. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) forecast as recently as February was for 2020 demand to rise by 0.8% against the 2019 level. Just one month later, in early March, it revised its forecast from a demand increase to a decrease – of 0.1% against 2019 and a fall in 1Q20 alone of 2.5%. Not since 2008/9, in the global financial crisis, had the world seen a decline in oil demand.

Clearly OPEC was doing the same calculations and coming to the same conclusion – that the oil market was going to be substantially oversupplied in 2020 unless something was done about the supply side of the equation. While initial estimates of the new cuts needed to balance the market were 600 kbd, by the time of the OPEC+ meeting the cuts needed were reportedly 1.5 mbd. Such large cuts proved impossible to agree on and hence we saw the announcement of planned significant increases in production by Saudi Arabia and Russia.

With falling demand and rising supply, how does the market get back towards balance and recover some stability. Both sides of the equation matter going forward – rising demand over time and reduced supply sooner rather than later.

A few weeks ago, the IEA cut its 2020 base case demand forecast by 1% given that the coronavirus had spread. With the OECD lowering its global growth forecast for 2020 to 2.4%, the IEA’s central forecast was a 2.5% fall in world oil demand in 1Q20. It also suggested demand could broadly return to normal in the second half of the year, meaning that 2020 demand would only fall by a modest 0.1%. Just a few weeks later, that figure seems overoptimistic and the IEA’s low case of a fall in 2020 demand of 0.75% may end up being closer to the truth.

Looking forward, on the assumption that economic activity does recover later in 2020 and into 2021 – albeit from a lower base – oil demand is expected to rise at around 1% pa from then until 2025, with petrochemical demand and overall demand from India and China rising over the next few years. However, the challenge from efficiency improvements is only set to grow, with new vehicle efficiency standards being implemented (although not in the US). Renewables pose a serious medium-term challenge to oil demand, and while cheaper oil may lead some to rethink their commitment to renewables, that seems unlikely to be a widespread phenomenon – although with renewables costs coming down, subsidies may also be reduced.

Demand growth is a steady, cumulative but relatively unspectacular route towards a balanced oil market. Overall 2020 demand will be at best flat, at worst down by 0.75% and certainly take time to recover. It is supply restraint on the part of the major players that is the key to solving the market dislocation in the short- to medium-term. Given that it was the failure to agree on supply cuts in early March that prompted the recent sharp falls in prices, how likely are the major producers to reach an agreement?

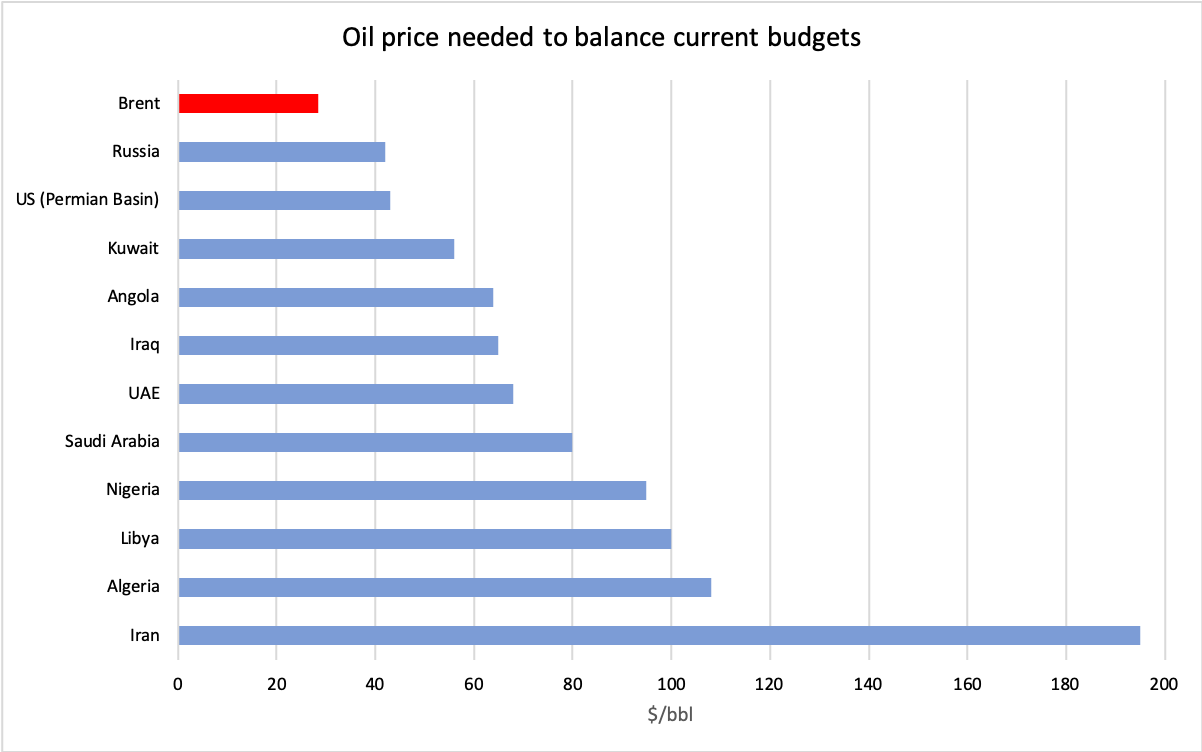

The three key oil actors are the US (particularly shale oil), Russia and Saudi Arabia. The US is most immediately affected by a falling oil price since the companies are all in the private sector. We have already seen problems emerging there since at current prices a lot of shale output will be unprofitable, and financing difficult to secure. Companies will need to rapidly cut capex, opex and dividends and potentially face bankruptcy (Whiting Petroleum already has); over time this will lead to a decline in US output and the abandonment of some production. Some estimates suggest that shale output will fall by 20-30% by the end of 2021. However, even with the Permian Basin breakeven of $43/bbl, we should not count the shale sector out completely – it has proven resilient in the past and the IEA itself has said “shale will come back”. Clearly there will be a short-term production response from the US given the low-price environment, but it could well rebound if prices recover.

A confrontation was perhaps inevitable in some ways. Demand had been rising gently before a sudden rapid decline for entirely unforeseeable reasons. OPEC+ was fractious since at least one of the two major participants had concluded that other producers were gaining market share at its expense and felt able to challenge the guilty party (US shale) from a position of relative strength. A Russia/US/Saudi Arabia oil price crunch was probably coming at some stage – perhaps not quite so soon and certainly not with the same dramatic effect.

Russia took the initiative last month to end its agreement with OPEC, on the announced grounds that there were free-riders taking advantage of the opportunity to increase their own output. Moscow is in a stronger position to survive a price war than it was a few years ago when it faced problems with both the rouble and foreign borrowings and it first allied with OPEC. Its budget is based on $42/bbl, it has kept expenditure largely under control, run a budget surplus in recent years and the rouble has a floating exchange rate. It has also created a sovereign wealth fund and has total FX reserves of around $570 bn.

Government spokesmen have said that a price of $25-30/bbl would be acceptable for up to a decade, suggesting the country will not compromise its position while the US shale threat remains serious. Analysis by the OIES suggests Russia could weather a low-price environment for at least three years. Russian oil companies also oppose the production cuts, although they are likely to have only a limited ability to raise their output and the lower prices will result in declining revenues for the sector overall.

Saudi Arabia launched a price war in response to the ending of the production agreement. From current output of under 10 mbd, the Saudis plan to raise production from April to 12-13 mbd. Riyadh’s ability to raise output quickly will be the main determinant of how prices move from here, since Saudi is the country with the largest spare production capacity. Many OPEC member states have seen production declines because of sanctions (Iran & Venezuela), war (Libya) and over-production (Angola), while Iraq is set on actually raising its output; it is the small group of Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies which has borne the burden of cutting output to stabilize prices.

Riyadh’s challenge is that the government’s Vision 2030 plan to diversify the economy away from oil needs oil revenue to finance it. The Saudi budget is balanced with oil at $80/bbl. The country can certainly survive on its financial reserves and external borrowing for some time – but not forever. There are also numerous social and political challenges within the kingdom which need funds to address them.

In the medium- to long-term a continuing oil price war is probably not sustainable for any of the major parties. All three require higher prices than today to maintain revenues and achieve their economic objectives – structural reform of the economy, growing financial reserves or maintaining employment. There have already been discussions between Presidents Trump and Putin, between Washington and Riyadh and, according to President Trump, between Moscow and Riyadh (although Moscow denies this). US oil producers have asked regulators to mandate lower output from the key producing state of Texas and to bar Saudi crude from US refineries. The rapid fall in prices has created strange new bedfellows.

In the short-term, supply cuts seem unlikely to completely compensate for the sharp decline in global demand and, with oil storage steadily approaching full capacity, some production shutdowns may be inevitable.

Ultimately, the road to a balanced oil market is all driven by politics. Government stimulus packages will drive GDP recovery and energy demand – albeit from a lower base – and will certainly not be instantly effective; overproduction will probably be addressed by some understanding between Riyadh and Moscow, with perhaps informal help from the US government, although probably not from all of the US shale industry – some of which may feel able to reinvent itself for a new world of lower prices and dramatically reduced demand.