A decade since Russia formally began to focus on its pivot to Asia, questions about its effectiveness linger, writes Valdai Club expert Nivedita Kapoor.

As Russia’s military operation in Ukraine continues, the West’s imposition of crippling economic sanctions have left little doubt as to its potential long-term consequences for Moscow’s policies regarding trade with other regions of the world. If the war drags on and sanctions against Russia continue, economic isolation and default loom large. Even if the country does manage to avoid a collapse, it will nevertheless bring into sharp focus the weaknesses in its eastern pivot, with long-term consequences for its global power projection.

A decade since Russia formally began to focus on its pivot to Asia, questions about its effectiveness linger. This scepticism emerges from three key factors: the non-fulfilment of the original aims of the pivot, unclear policy goals, and the on-going realignments in the Asia-Pacific. When it was launched, with the 2012 APEC summit generally seen as marking a formal declaration of intent, the pivot’s goals were described as the development of the Russian Far East, diversification of economic ties with the Asia-Pacific and the improvement of Moscow’s overall presence in the region. Several years later, Moscow announced a much grander vision of Greater Eurasia, which encompasses the countries of East, Southeast and South Asia as well as central Eurasia and Europe. In other words, the pivot to East was now subsumed within this broader framework, where the success of policies in the various sub-regions of Greater Eurasia would contribute to the overall fulfilment of the policy.

But this latest idea has yet to significantly progress beyond the conceptual stage, as there have been few practical developments to reach a meaningful conclusion regarding its future. In the meantime, the rise of the Indo-Pacific, regional concerns regarding an aggressive China, intensifying US-China rivalry and the formation of Quad and AUKUS have together accelerated the evolution of the regional balance of power. Even though Russia recognises the shift of global geo-politics and geo-economics to the East that will essentially determine the future of the world order, its military and diplomatic focus remains on the West, and the consequences of the invasion of Ukraine could potentially deeply constrain Russia’s ability to carry out its policy goals in the East.

Russia’s strategic goals in Asia

As Russia recognised the long-term shift in global politics, it repeatedly stated its intent to improve relations with the Asia-Pacific. The National Security Strategy lists the goals of Russian foreign policy: to develop the partnership with China and India, to ensure regional stability in Asia-Pacific, and to support regional multilateral institutions, including ASEAN and its various formats. President Vladimir Putin in his maiden address to the foreign policy advisory board reiterated that the shifting of the “centre of gravity of world’s politics and economy” to the Asia-Pacific necessitated that Russia should “continue vigorously developing relations with the states” in the region, in line with the aim of creating the Greater Eurasian Partnership.

This linkage of the Asia-Pacific to Moscow’s Greater Eurasia plan underlines the importance of the region to its overall positioning in an evolving international order. The same sentiment also informed the foreign policy concept of 2016, which included the idea of establishing a joint development space for ASEAN, SCO and the EAEU, maintaining peace in Northeast Asia and building ties with Japan. However, as Japan, South Korea and Singapore have joined US sanctions, with India walking a tightrope but not pleased with Russian actions, Moscow’s goals in the region have been dealt a blow by its own actions in Ukraine.

The goals of the pivot — ten years on

The focus on the development of the Russian Far East (RFE) has yielded results in the form of higher growth compared to the national average and increased investment, but the size of the market remains small. By 2019, it was estimated that only about 20% of the region’s FDI or about $2 billion had arrived in the RFE from foreign investors. Earlier, Western sources had contributed most of the FDI in the RFE, but this has dried up since the imposition of Western sanctions after annexation of Crimea in 2014. The expectations of Chinese FDI too have not materialised, and the Programme of Cooperation between Northeast China and Russia’s Far East and Eastern Siberia (2009–2018) could not achieve its goals; prompting the creation of a new programme for 2018-24. China, Japan and South Korea are its main trading partners for the region; but the overall amount in bilateral trade remains not very significant. Japan has had some success in the small and medium business sector in RFE, even though the volume currently remains limited. The New Northern Policy of South Korea saw Russia an important link but investments declined in the RFE after 2014 and issues like inadequate infrastructure and the overall economic environment have limited trade opportunities. India has only recently turned its focus to the region and announced a $1 billion line of credit in 2019, but is yet to operationalise it. The region is new for Indian businesses and their level of interest in it remains to be seen. In other words, the RFE has yet to achieve its stated ambition of being integrated into the Asia-Pacific economy.

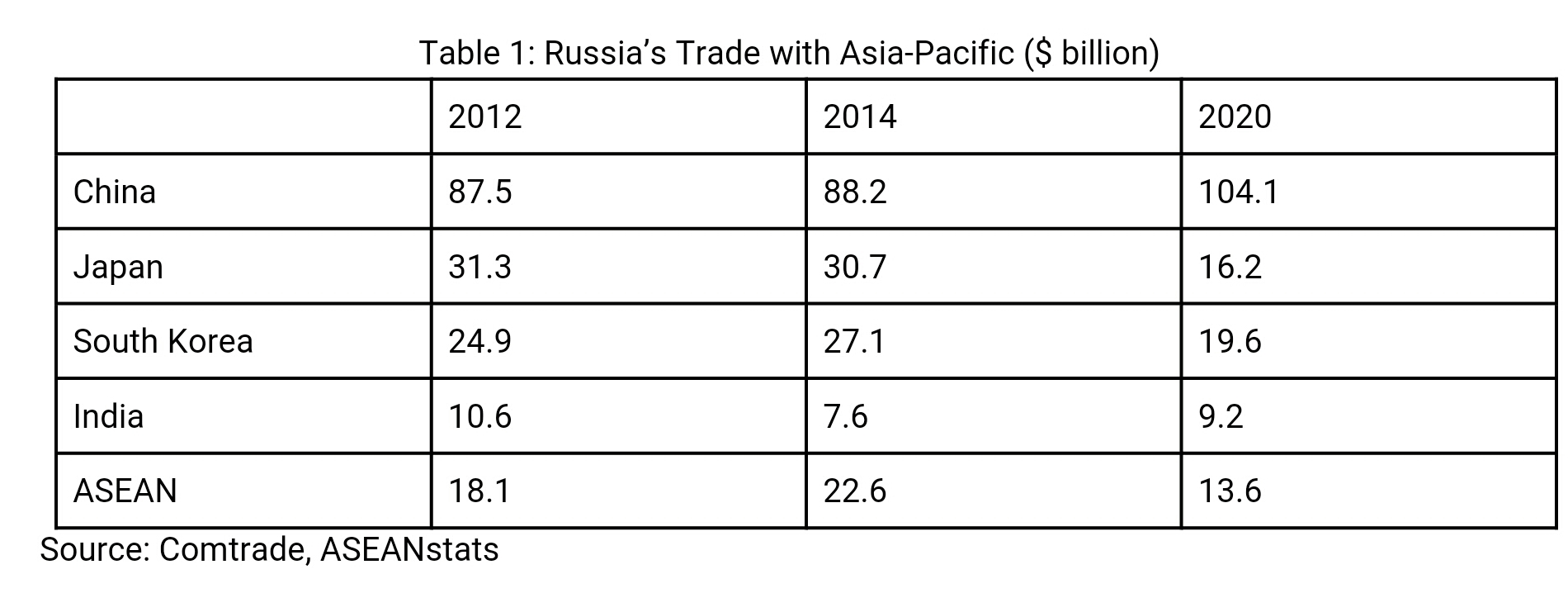

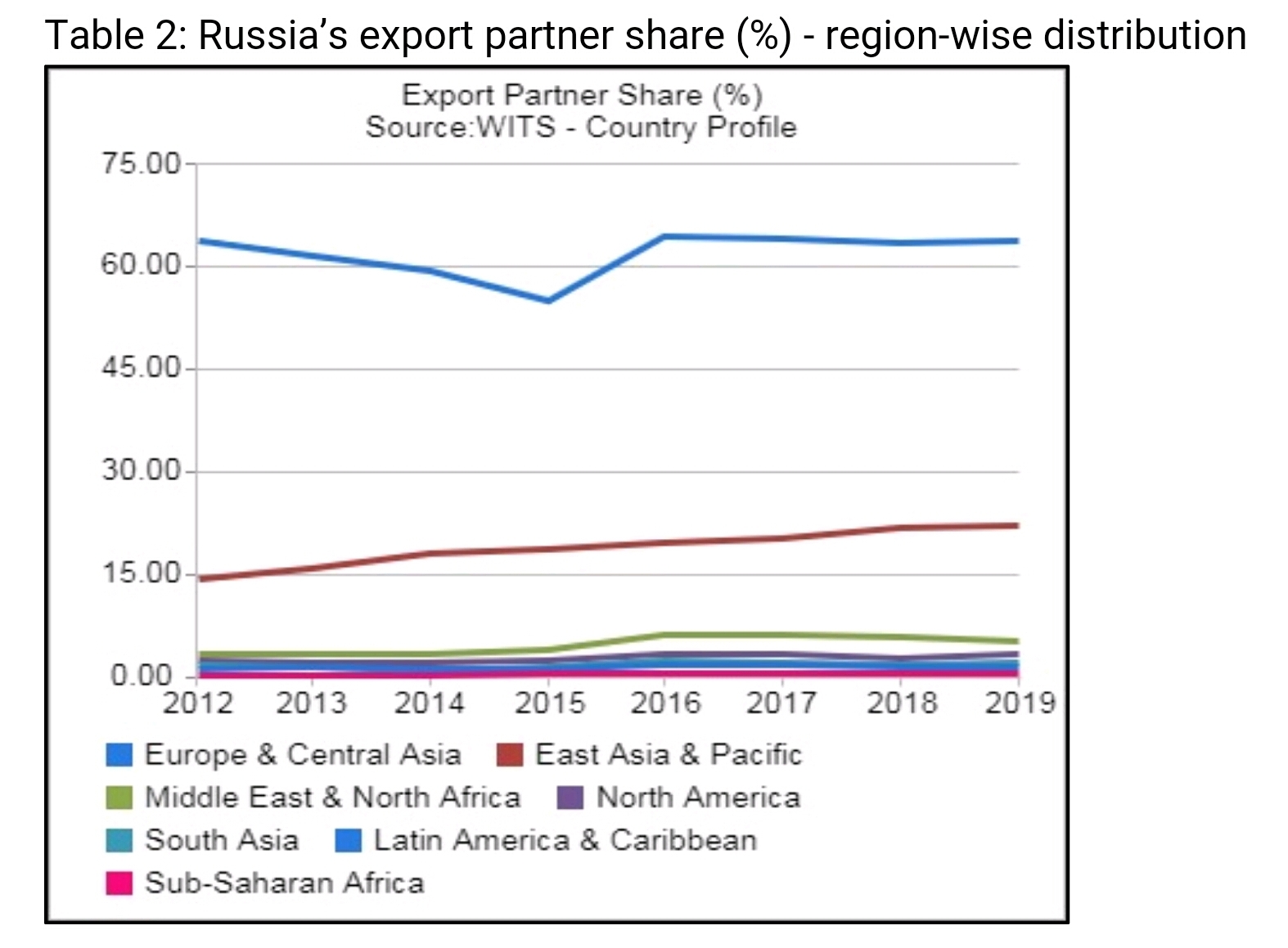

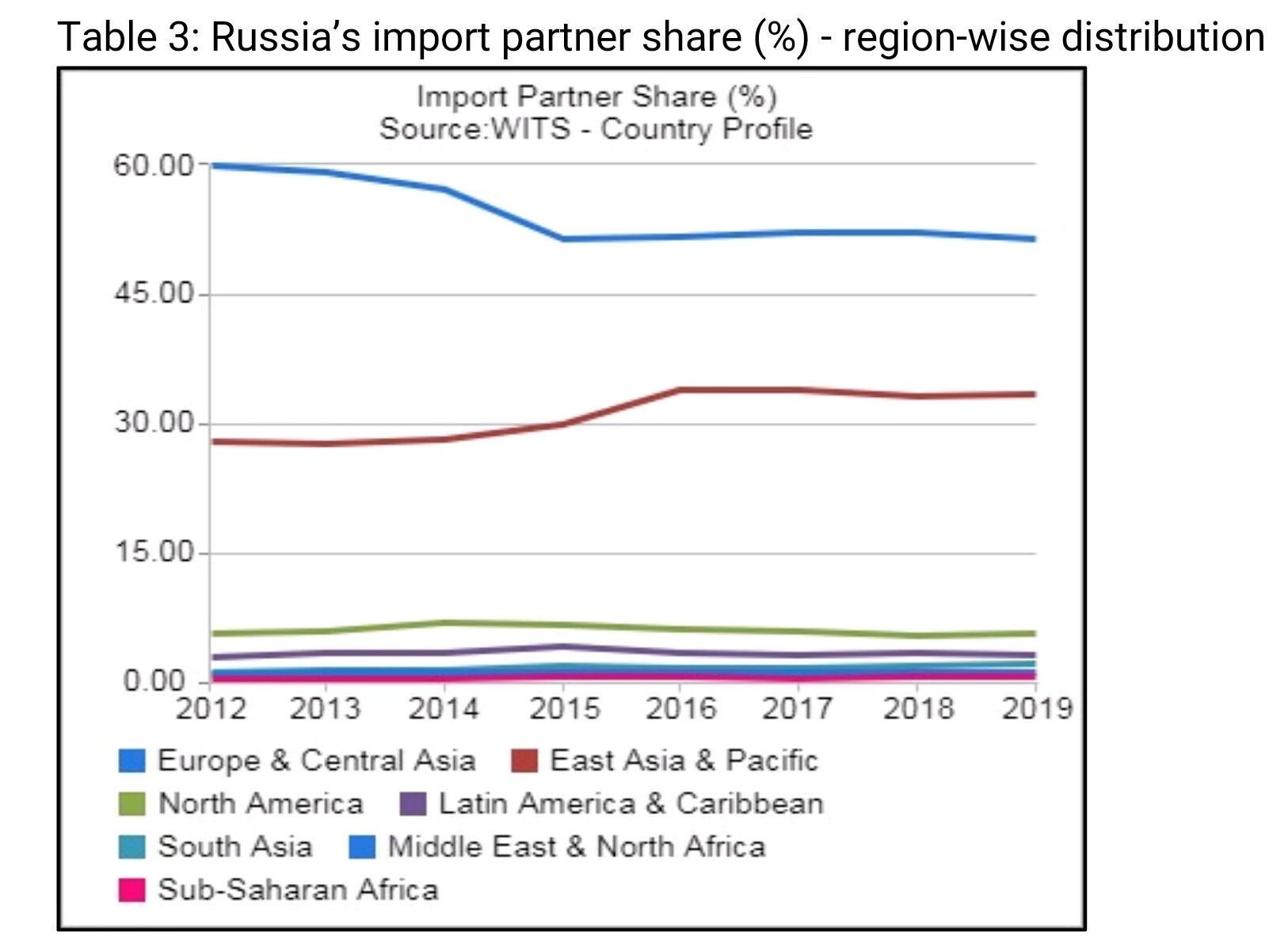

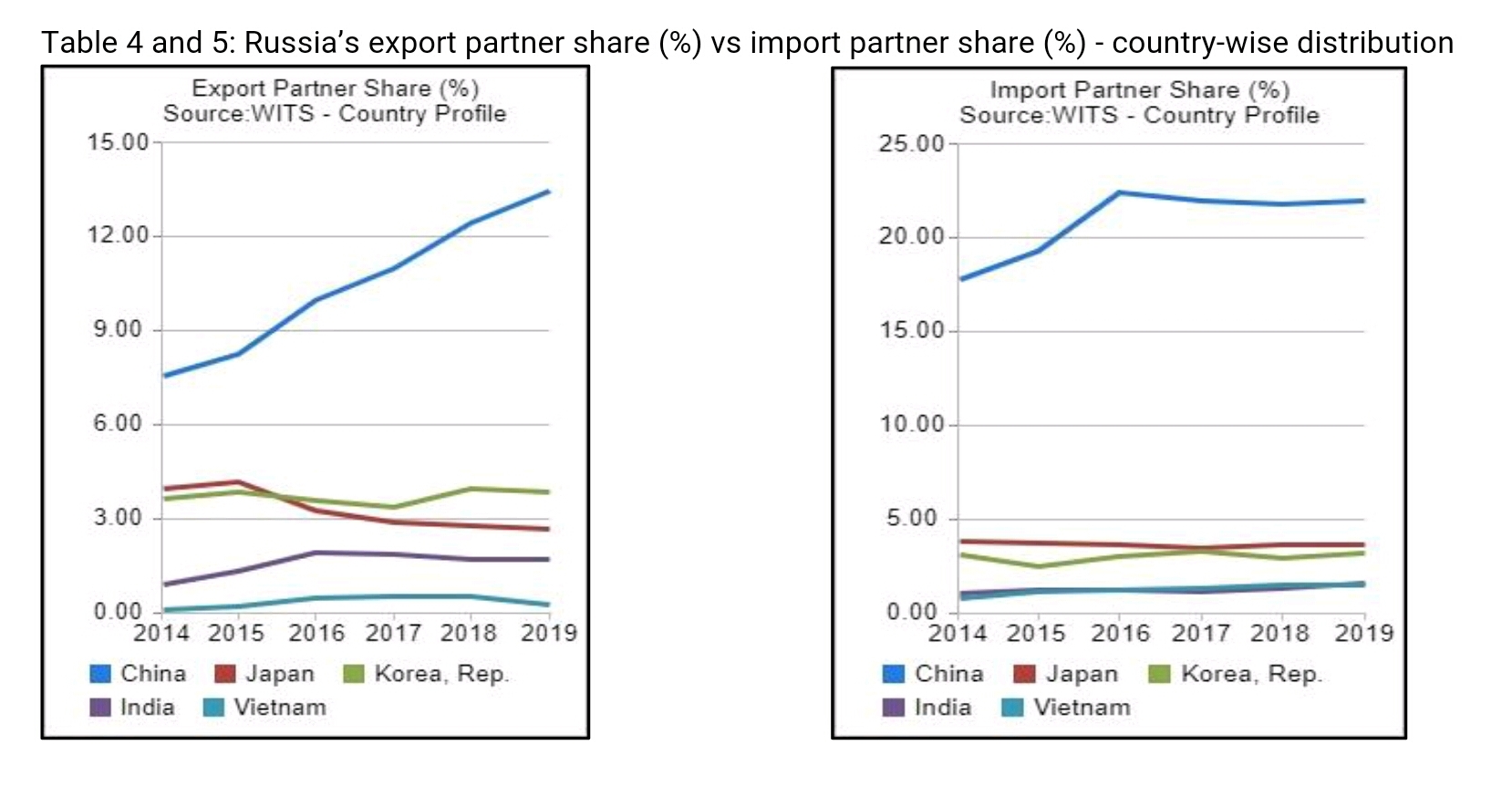

Regarding the goal of diversification of economic ties with Asia-Pacific, much of the increase in trade with the region can be attributed to the growing trade ties with China, instead of a broader diversification with the region, as seen in Table 1 below. Already, Russia’s trade patterns have developed in ways that were highly skewed towards China in East Asia and the Pacific, as revealed by the following graphs. The imbalance further continues as China’s share of Russia’s trade turnover stands at 18%, with the latter only accounting for 2% of the former’s trade.

Source: WITS data, World Bank

With Russia already not a major trade partner for the region, the economic sanctions will only worsen the state of affairs for Moscow. It remains to be seen if Russia can use mechanisms like China’s UnionPay and Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) and trade in national currencies to offset some of the challenges. Also, the willingness of other countries after factoring in secondary sanctions remains unclear at this stage. Even if some sanctions are bypassed, it is clear that a weak economic situation in Russia will have a negative impact on its trade figures, further slowing down the already underwhelming implementation of the eastern pivot on the ground.

As the largest regional trade partner, this makes China’s attitude towards Western sanctions critical for Russia, but it will also have a political cost for Russia amid ongoing economic isolation. It will see its leverage with China deteriorate, while being unable to diversify its ties with other states, which might be cautious about defying Western sanctions based on their own interests. Russia also does not have leverage in regional trade due to its past inability to become part of regional value chains and the non-liberalisation of foreign trade.

It does remain a prominent arms supplier to the region, even though SIPRI estimates reveal

that its arms exports to Asia and Oceania fell 36 percent between 2016–20 and 2011–15. This was mainly on account of reduced supplies to India, which has again picked up pace in recent years, including the S-400 missile defence system. It is the leading arms supplier for India and Southeast Asia, and the second largest arms supplier to the overall region. Since 2014, military cooperation between Russia and China has increased, leading to not just increased joint exercises but also a higher level of military trade (including S400, Su-35s, and helping China build a missile defence system). While India has diversified its arms imports in recent years, roughly 80%

of its military equipment is of Soviet/Russian origin. The threat of sanctions and Russia’s growing closeness to China is now prompting some calls in India to reduce this dependency, amidst sustained tensions on the Sino-Indian border. While an immediate shift in the short-term would not be possible, and it remains to be seen how India exercises its own leverage vis-à-vis Russia as a major importer, a long, drawn-out war would not be without its consequences for Russia’s engagement with India. What kind of Russia emerges out of this crisis will determine Indian calculations, especially in the light of the increasing salience of US for Indian foreign policy.

Despite being the leading supplier of arms to Southeast Asia, Russia’s overall engagement with the regional organisations as well as individual ASEAN states has been slow in developing. While Russia has improved relations with traditional partners like Vietnam, its engagements in the economic and political domain remain at a much lower threshold compared to that of other regional powers. Russia has sought to position itself as an independent player in the region, but its efforts are still on-going and getting increasingly complicated amidst the growing US-China rivalry. Arms sales in the region, while playing a role in building bilateral ties, do not necessarily translate into an increased role at the geopolitical level. The region remains home to a range of powers that enjoy deep defence networks with regional powers and are better connected economically, diplomatically and culturally when compared to Moscow.

This is borne out in the assessment of Russian regional influence by the Lowy Institute’s 2021 Asia Power Index, which classifies the former superpower as a middle power in Asia. While it performs well in terms of resilience (availability of resources, nuclear deterrence), military capability and defence networks; it scores very low in economic relationships. In totality, given its available strengths, the index reveals that Moscow continues to exert less influence than expected. The difference between the leading power in the index (the US) and fifth (Russia) is also vast. The former gets a comprehensive score of 82.2 while the latter comes in at 33.0 points. Even in terms of military capability, one of its strengths, the difference in power with the US is large (91.7 vs 51.6). This reveals the weakness of Russia’s underlying policy in a region with the presence of major powers like the US and China; as well as influential middle powers including Japan, India and Australia.

Thus, despite its repeated talk of focusing on the Asia-Pacific, Russia has been unable to make this transition. The diversification in Asia has suffered due to a range of factors including limited historical experience, weak economic linkages, the presence of other influential powers, and a weak strategy — all of which is set to be compounded by the economic and political consequences emanating from Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, if a negotiated deal is not reached.

These details together reveal the key shortcoming in Russian engagement with the East: that its traditional levers of influence and geographic presence are not enough to make it a powerful regional power. The pivot rightly sought to address these concerns but the overall results remain underwhelming ten years since the policy was first announced. While there is no denying Russia’s interests in the Asia-Pacific, it exercises varying levels of influence across its various sub-regions. In any case, the pivot East would have to be a long-term policy measure for Russia, but a decade down the line, the non-achievement or slow progress on some of the key aims of the policy pronouncement should be a major cause for concern.

The changing East and Russia’s response

This is also because while Russia seeks to realise its eastern pivot, the region has undergone a major transformation, with deep implications for its positioning. The intensification of the US-China rivalry and the reimagining of the region as the Indo-Pacific, not to mention cooperation among states in the Quad and AUKUS format, are issues where Moscow will face key questions regarding its own policy formulation. Russia has opposed the Indo-Pacific notion and has reservations about AUKUS, which also found an expression in the recent Sino-Russian joint statement. But its other strategic partner in the region — India — has embraced the Indo-Pacific and Quad, having grown increasingly concerned about the rise of an aggressive China. Other regional powers like Japan and Australia are also increasingly interacting with each other and key Western partners amidst increasing concerns about the kind of power China will emerge to be, and recognising the need to ensure a ‘more balanced Asia.’

Ideally, Russia too would benefit from an Asia that is multipolar, and where its engagement in the region is not disproportionately dependent on China. Till now, Russia’s policy was to maintain and improve ties with traditional partners like India and Vietnam to prevent such an outcome; even as relations with China reached their best level in history. It did not take China’s side in its territorial disputes with its neighbours, and even played a quiet role in bringing New Delhi and Beijing to the table after the border clashes in Eastern Ladakh in 2020. While Russia walked a delicate balancing act, the choices were already getting more complex for Moscow as the US-China rivalry grew stronger, with regional states too recalibrating their policies. And now, Russia’s own actions are set to jeopardise its balancing act in Asia, fuelling a tilt towards bipolarity, decreasing the leverage with China, and potentially negatively impacting relations with partners like India worried about a closer Moscow-Beijing engagement.

If Russia does end up being closer to China, with lesser independence than before, it will have deep implications on how the former superpower conducts its policy in Asia. Its attempts to position itself as a balancer that is not a threat will be under stress if the states of the region perceive it as an economic pariah that is too close to China, alongside a weak economic and political presence. This also has implications for the broader Greater Eurasia policy, which suffers from a weak eastern leg. Without considerable resources to spend on building its regional influence even before the paralysing sanctions had hit, Russia now faces the prospect of being reduced to a further weaker position in Asia. This also hits Russia’s stated goals of diversifying regional ties, strengthening its position as an ‘independent pole,’ and being a participant in the building of the new regional order.

Thus, it is clear that how the ongoing crisis is resolved — whether through a diplomatic resolution or military means or a long-drawn out war — will have an impact on Russia’s policy towards the East as well. And it would be much better if diplomacy prevails at the earliest, otherwise the long-term consequences for Moscow’s power projection in both the East and the West would be.