Russia and Middle East Need International North-South Transport Corridor

© Sputnik/Sergey Subbotin

The main advantage of the North-South international transport corridor over other routes is a significant reduction in the time spent on transportation. Its launch would contribute to the formation of a macro-regional transport and logistics system - the Eurasian transport framework, which will serve as the basis for the development of trade and investment partnerships within Eurasia, says Evgeny Vinokurov, speaking at the fourth session of the 11th Valdai Club Middle East Conference – 2022. We publish the main theses of his speech.

Although the agreement to establish the multimodal International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) was signed 20 years ago, the corridor is still not operational. However, there are now a number of factors that will support the INSTC’s successful operation. These include the EAEU’s increased engagement with India, Iran, and other South Asian and Gulf countries; the substantial potential for linking the INSTC with latitudinal transport routes; accelerated digitalisation processes, and a dramatic strengthening of the climate agenda. In this context, the study estimates the INSTC’s cargo potential to be between 14.6 and 24.7 million tonnes by 2030.

The multimodal INSTC connects the Nordic countries and the north-western part of the EAEU to the Gulf and Indian Ocean states via the Caucasus and Central Asia. The corridor includes rail, road, air, sea, and river transport infrastructure. The unique North–South route creates opportunities to link with other global and regional East–West latitudinal transport corridors. These include the Eurasian Trans–Siberian railway, the Europe–Western China international transit corridor, corridors No. 5 and 8 of the Organisation for Cooperation of Railways, the Transport Corridor Europe–Caucasus–Asia, the international Lapis Lazuli transport corridor, and the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation’s transport corridors. EThus, the launch of the INSTC contributes to the establishment of a macroregional transport and logistics system: the Eurasian transport framework. The construction of this framework lays the groundwork for the development of trade and investment relationships within Eurasia and addresses the need to accommodate the long-term economic interests of many countries of the Eurasian continent, in particular those that are landlocked.

The International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) currently presents a mosaic of transport and economic links that differ in terms of infrastructure development and that offer a broad diversity of political relations with Russia and other partner countries. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the INSTC is a reciprocal projection of mutual interests of Russia and its partners. Transport interconnected infrastructure is shaped for decades to come. It is for this reason that from Moscow’s perspective the INSTC is a promising macroeconomic structure that is linked to a multitude of related sectors, including the downstream sector, electric power, communications, and tourism. This infographics was prepared for the Third Russia-Iran Dialogue.

Infographics

The primary advantage of the INSTC over alternative routes, including the sea route through the Suez Canal maritime route, is the significant reduction in transport time. For example, it takes 30 to 45 days to deliver cargoes from Mumbai to Saint Petersburg by the traditional route through the Suez Canal, while the INSTC land route delivery times may vary from 15 to 24 days. Moreover, using the Eastern route of the corridor that runs through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan can reduce delivery times to 15–18 days. Reduced delivery times are critical for many products, including food, textiles, household appliances, consumer electronics.

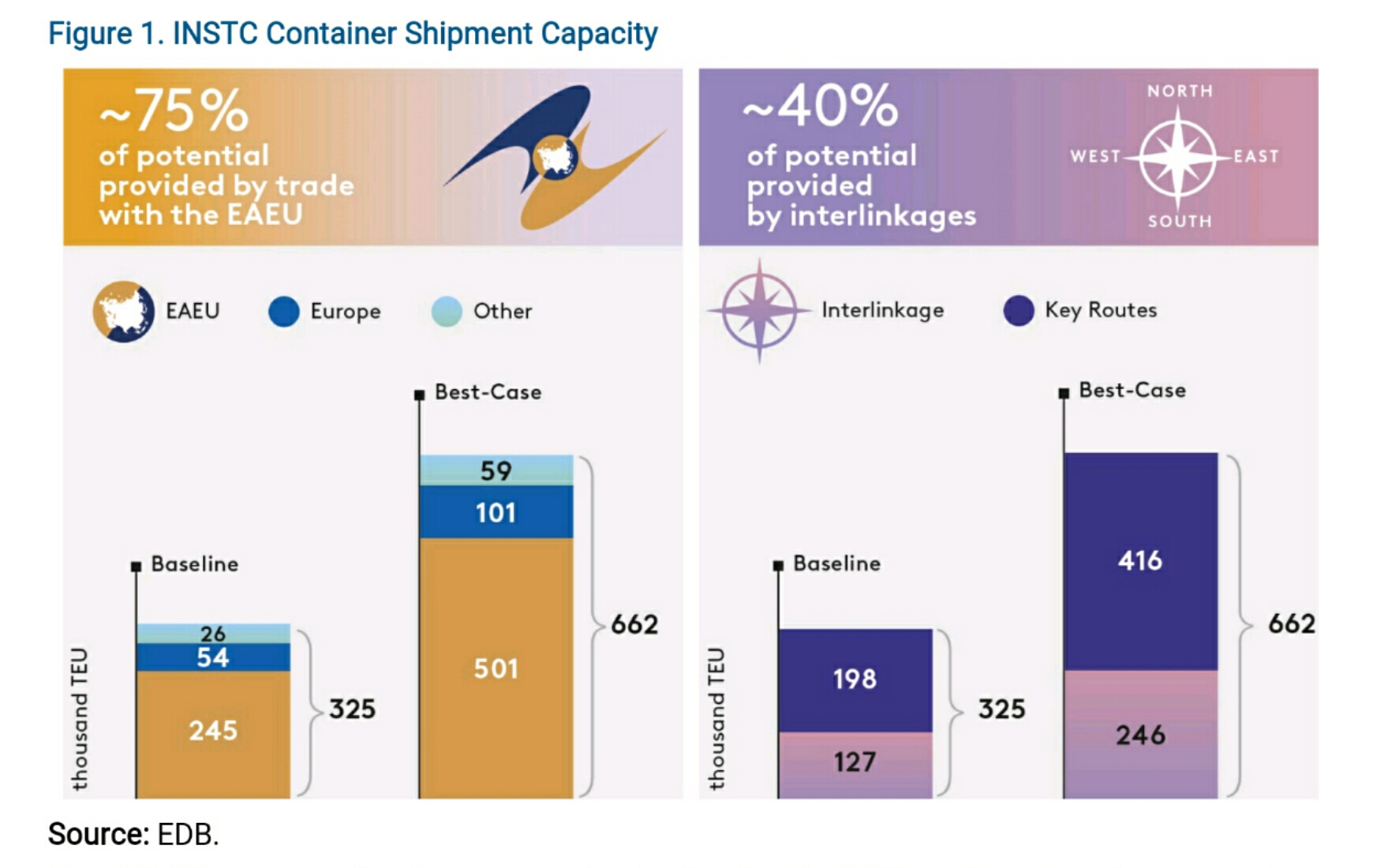

This study estimated baseline and best-case scenarios for container shipment along the INSTC, which may range from 325,000 to 662,000 TEU (5.9 to 11.9 million tonnes) by 2030. The impact that may be produced by interlinking the INSTC and Eurasian east-west latitudinal transport corridors is equivalent to 127,000–246,000 TEU (2.3–4.4 mln tonnes), or about 40% of total potential container freight traffic (Figure 1). Currently the main INSTC product categories suitable for containerisation are food (excluding grain and bulk oil), metals (ferrous and non-ferrous, and metal products), wood, wood products, paper, machinery and equipment, mineral fertilisers, textiles, textile goods and footwear, etc.

Expansion of INSTC container freight traffic is of considerable interest to the EAEU member states. By 2030, the development of freight traffic between them and the South Asian and Gulf countries may amount to 245,000 – 501,000 TEU (4.4 to 9 million tonnes), or about 75% of the total potential container traffic (Figure 1). The main contribution to potential container traffic can be provided by the freight flows between the EAEU on the one hand and Azerbaijan, Iran, India, and Pakistan on the other. Interlinking the INSTC and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars latitudinal railway route can also have a significant favourable impact on the EAEU member states. That connection will enable expansion of railway container traffic between the EAEU, Georgia, and Turkey.

All three INSTC routes are critical for unlocking transport and transit capacity. However, the greatest opportunities come from the development of two railway routes — Western and Eastern — which account for approximately 60% and 24% of container freight shipment capacity, respectively. It should be mentioned that railway transport is comparable to deep-sea maritime transport in terms of both direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, but it is the most environmentally friendly mode of transport in terms of particulate matter and mono-nitrogen oxides emissions. At the same time, road and inland water freight traffic capacity is significantly less than railway capacity, estimated at 45–50 thousand TEU (or 0.8–0.9 million tonnes) and 10–20 thousand TEU (0.2–0.4 million tonnes) by 2030, respectively, depending on the scenario.

The INSTC’s main product is non-containerised grain. By 2030, the flow of grain cargo via the INSTC is expected to range between 8.7 and 12.8 million tonnes. Thus, its transport volumes will continue to exceed the potential container freight traffic generated by all other product categories combined (5.9 to 11.9 million tonnes). As a result, by 2030 the aggregate potential INSTC freight traffic, including the two types of product categories, containerised and non-containerised cargoes, is expected to reach 14.6–24.7 mln tonnes.

Additionally, the study’s findings suggest that both tariff and non-tariff barriers constrain the the potential expansion of INSTC freight traffic. Thus, the gravity model indicates the following: the reduction of costs of obtaining, preparing and depositing documents for border and customs control in the INSTC Agreement member countries from the current USD 376.12 to the European average of USD 79.65 is associated with the increase of foreign trade by 5.9% of the 2019 figure (or USD 59.08 billion). Additionally, digitalisation has a positive and statistically significant effect on foreign trade growth, contributing to the establishment of “seamless” transport routes.

In the long term, the INSTC may become a development corridor for the EAEU. Apart from increasing trade volumes, the development of the INSTC facilitates the construction of industrial parks and special economic zones along the transit route, as well as industrial cooperation and the establishment of production and logistics chains with major emerging economies in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

More information on International North-South Transport Corridor can be found in this report published by the Eurasian Development Bank.

Transport routes are like rivers, where water always fi nds a way to continue its fl ow. It is not a coincidence that transport routes are often referred to as arteries. But what comes first – a riverbed or the water, the fi rst representing the strategic will of states and the second the contents, i.e. goods resulting from the balance of interests between businesses and consumers? Global trade routes such as the North–South Project can be viewed as social and economic phenomena largely shaped by the political will of the countries that promote these trade corridors based on their understanding of common interests.

Reports

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.