The world economy has made large welfare gains during the period of rapid globalization in the last decades. The distribution of these gains between and within countries may not match the equity perceptions of all observers, but their presence is indisputable (Helpman 2018). Especially in a global economic crisis, it may be negligent to forgo these benefits. Still, voices calling for more nationally-oriented protectionist policies are out there, writes Holger Görg, Professor of International Economics at the University of Kiel.

Modern manufacturing has for the last decades been increasingly organised as a bundle of transactions taking place in global value chains (GVCs). This has undoubtedly contributed to worldwide growth and improvements in efficiency in production, though critics also point to the unequal distribution of such benefits across and within countries (Antras, 2021; Helpman, 2018). While current GVCs are highly efficient, specialized and interconnected, they are also potentially vulnerable to adverse shocks at national, regional or global levels. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a case in point, being a powerful illustration of how a global pandemic can cause such disruptions in GVCs. Initially, the emergence of the virus and the lockdown measured put in place to combat it caused severe disruptions in production activity in the first quarter of 2020, as China and other Asian economies were first hit by the outbreak, which subsequently spread globally.

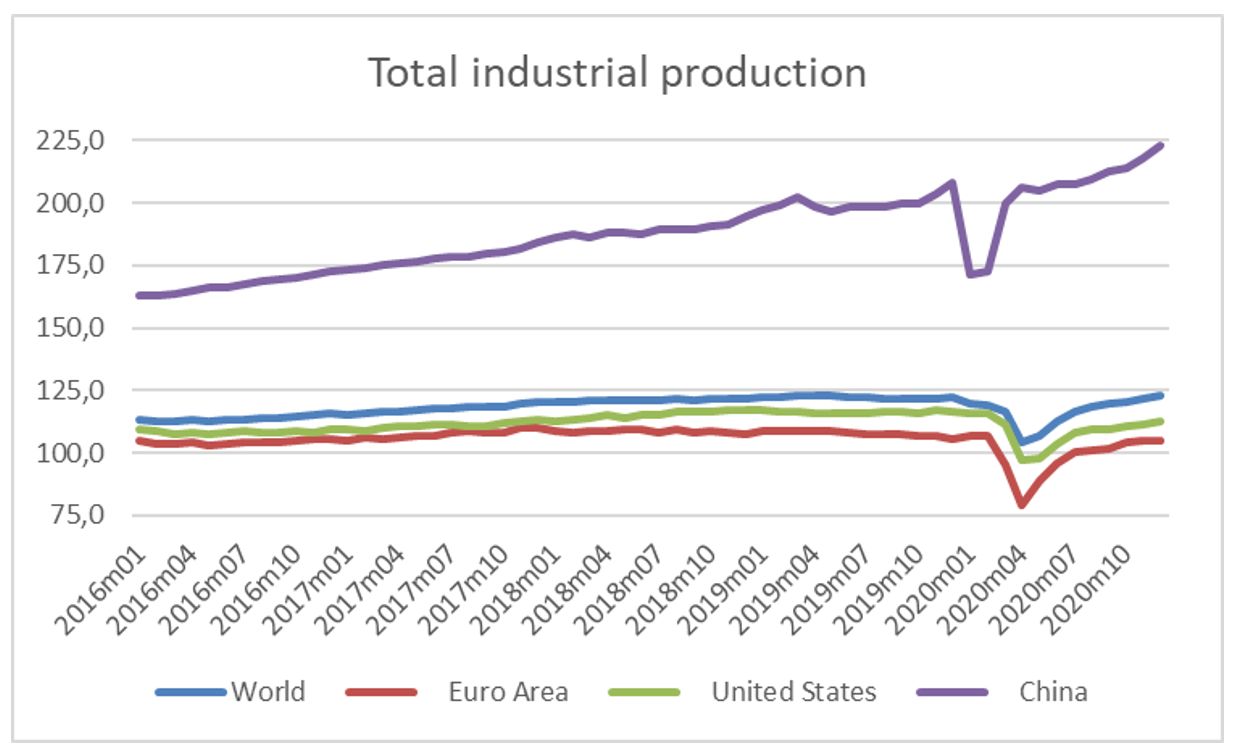

This is illustrated by the data in Figure 1, which shows the development of total industrial production in the world (blue line) as well as the US, the Euro area, and China. It is noticeable that China was hit earlier than the rest of the world – as is to be expected since it was the first country to implement lockdown measures – but has also since recovered quite speedily and seems to be on its pre-COVID-19 trajectory again. While the rest of the world also appears to be re-bouncing, this recovery is less rapid than in China.

Note: Growth expressed as index fixed at 2010 = 100

Source: CPB World Trade Monitor

The delay in the slump in industrial production in the world – compared to China – has at least two reasons. One is of course the spread of the virus, which dissipated from China and made its way around the globe leading to implementations of lockdown measures. The other reason is that global production is organised in global value chains, and China is at the heart of many of those. It is for a good reason that China is also referred to sometimes as the factory floor of the world. A drop in industrial production in China – much of which is intermediate inputs – affects firms located in other countries involved in the Chain, albeit with some delay.

However, China is of course not the only country that is important as a supplier in global value chains but they are spread around the world. Apple, e.g., uses intermediate inputs for its products from countries as diverse as Malaysia, South Korea, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US. During the pandemic, production in all of these countries was hit at some stage, also affecting their ability to supply intermediate inputs to firms located in other countries. The ensuing supply chain disruptions has prompted policymakers in many countries to address the need for economic self-sufficiency, along with strategies to better deal with global risks, even at the expense of the efficiency and productivity gains that globalization through its international division of labour has undoubtedly brought.

Is this really the best way forward?

Decisions about suppliers are taken by firms, not countries. Management of firms makes conscious decisions about whether to produce their own inputs or purchase them from the market, and how many suppliers from how many countries to source from. As establishing relationships with suppliers is costly, it is typically appropriate to limit the number of suppliers. This choice then, however, also implies that firms may suffer painful production losses when they cannot operate due to disruptions in one or more of its suppliers. What matters for the management’s decision problem is then a clear idea about what the costs of choosing a supplier are, and what the probabilities are that a particular supplier relationship may be disrupted through an external shock – be it, e.g., a supplier-specific production shock, a geographically localised natural disaster (such as the Fukushima disaster 10 years ago), or a global pandemic. While the costs may be fairly straightforward to calculate, the risk of disruption is, of course not known exactly. In particular, the probability of extreme events such as the Corona pandemic is difficult to pin down. Still, the emergence of this particular pandemic will almost certainly lead to a reassessment of disruption probabilities by many firms.

Does this then mean that shortening of supply chains is the prudent way forward?

It is important to be clear about the nature of the shock that generates the disruption. Generally speaking, these shocks can be country-specific – if, e.g., a country is hit by a natural disaster – or sector specific, if only a particular sector of the economy is hit (Caselli et al., 2020). It is clear that the Corona pandemic is a systemic shock that affects all countries and all sectors of the economy; therefore, it is not clear how it can be argued that a less pronounced international division of labour would facilitate national coping with the shock. If all economies – including one’s own – are in lockdown, there is nothing to be gained from shorter supply chains as it does not matter whether your supplier is far away or in the same town. Suppliers that are geographically closer to the production site are not necessarily safer, unless it is precisely the long transport routes that a shock breaks. It is therefore not clear that shortening of supply chains necessarily leads to greater security of supply.

By contrast, natural disasters actually offer an example of the stabilizing effect of international diversification in a supply chain. When a country is hit by an adverse shock, and production is negatively affected, then firms relying on supplies from this country may do well by having alternative suppliers in other countries that can produce the same or similar inputs. Economic research looking at disaster-related supply chain disruptions shows that while adverse shocks to individual suppliers spread through production networks and cause significant damage to customers, especially when specific inputs are involved (Barrot and Sauvignat 2016), companies that have a well-diversified global supplier structure are more resilient. This is, e.g., found by Todo et al. (2015) for the case of the 2011 tsunami in Japan and Kashiwagi et al. (2018) for Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

However, it is highly uncertain what this will mean for the globalization of global supply chains because the pandemic is a systemic shock that affects all countries, industries and companies equally. An alternative to shortening or diversifying the supply chain is to keep inventories. Management will have to balance the cost of keeping stocks of intermediate inputs against the cost of sourcing inputs from suppliers and the risk of supply chain disruptions. This may make it more likely that companies will engage in more inventory holding than before, keeping stocks of inputs, in particular those that are highly crucial for the production process. This will increase resilience to shocks, but is not necessarily associated with regionalization or re-nationalization of supply chains.

The world economy has made large gains in development and growth during the period of rapid globalization in the last decades. While not every country, or every individual in a country, has benefited equally from this, their presence cannot be disputed (Helpman 2018). Especially in a global economic crisis, one should think carefully about forgoing these benefits. Still, voices calling for more nationally-oriented protectionist policies are out there.

Since the start of the pandemic, the lessons of the great crisis of 2008-09 have been frequently invoked. One of these was, of course, that protectionism cannot be the right way forward through such a crisis. This should not be forgotten lightly.

References

Antràs, Pol. 2021. “Conceptual Aspects of Global Value Chains.” World Bank Economic Review 34 (3): 551-574.

Barrot, J.-N. und J. Sauvagnat (2016), Input specificity and the propagation of idiosyncratic shocks in production networks, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(3), S. 1543–92.

Caselli, F., M. Koren, M. Lisicky und S. Tenreyro (2020), Diversification through trade, Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1), S. 449–502.

Helpman, E. (2018), Trade and Inequality, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Kashiwagi, Y., Y. Todo und P. Matous (2018), International propagation of economic shocks through global supply chains, WINPEC Working Paper E1810.

Todo, Y., K. Nakajima und P. Matous (2015), How do supply chain networks affect the resilience of firms to natural disasters? Evidence from the Great East Japan earthquake, Journal of Regional Science 55(2), S. 209–29.