Since the beginning of 2020, the entire world is fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. At the end of November 2020 this is an unfinished story and nobody knows when and how exactly this very dramatic threat to human health and life will be defeated. Meanwhile the pandemic has also had serious economic and social consequences. Below we discuss key dilemmas faced by economic policies in all countries affected by the pandemic.

Stopping contagion or protecting the economy?

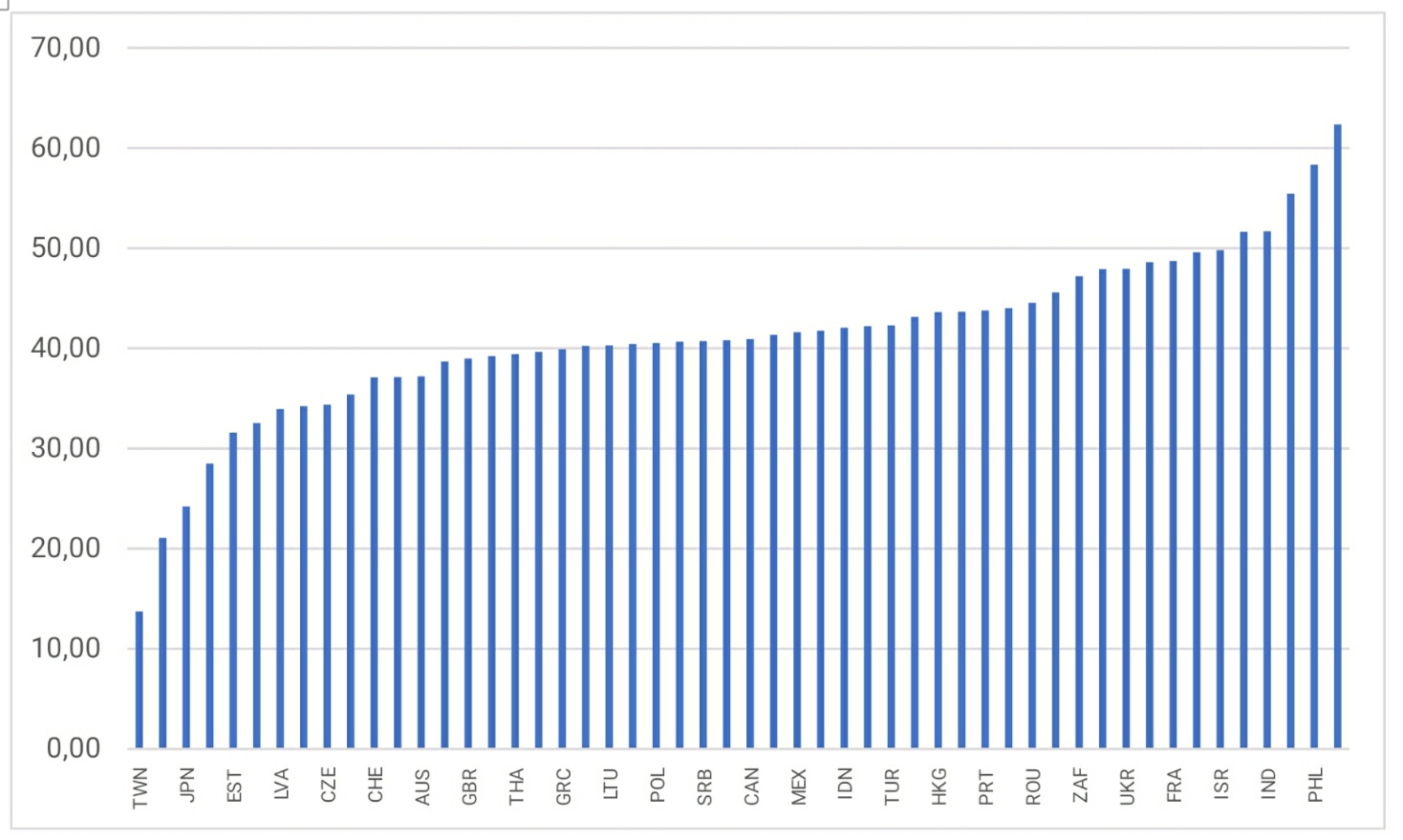

From the very beginning of COVID-19 pandemic, governments faced a fundamental dilemma: whether to introduce restrictions on people’s mobility and various forms of economic and social activity in order to stop/ minimize disease contagion or protect the economy? Figure 1 shows that in the first half of 2020 individual countries choose various strategies which did not fall into any clear regional pattern. For example, in all continents there were cases of relatively soft restrictions (Taiwan and Japan in Asia, Sweden and Finland in Europe) and tougher ones (China, Philippines and India in Asia, Peru and Colombia in Latin America, Italy and France in Europe). Quite often, the actual degree of lockdown differed from the initial declarations of the country’s authorities and dominant political narrative and evolved over time (Figure 1 presents an average level of containment measures in the entire first half of 2020).

Figure 1: Lockdown stringency (0-100), average of the H1 2020

Source: IMF

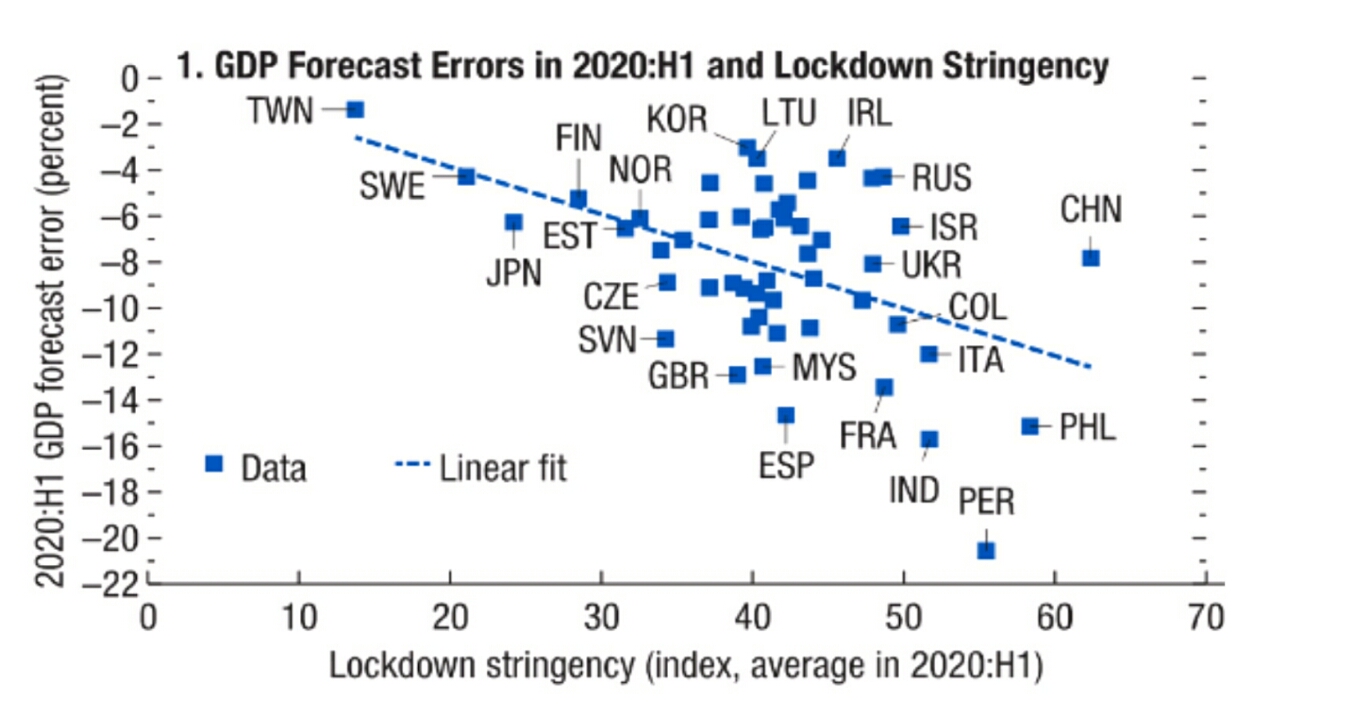

When the pandemic erupted, several governments believed that they could stop spreading the pandemic into their countries by closing their borders. This did not work – the pandemic is practically everywhere. And it has not been a short-term episode as some people hoped. The COVID-19 is already with us more than half a year and there is no light at the end of the tunnel so far. On the other hand, the heavy economic costs of pandemic and associated lockdown have become visible. Unsurprisingly, Figure 2 shows that there is a correlation between lockdown stringency and output losses (estimated as the difference between the IMF January 2020 forecast and the actual performance).

Figure 2: GDP forecast error and lockdown stringency (0-100), H1 2020

Source: IMF

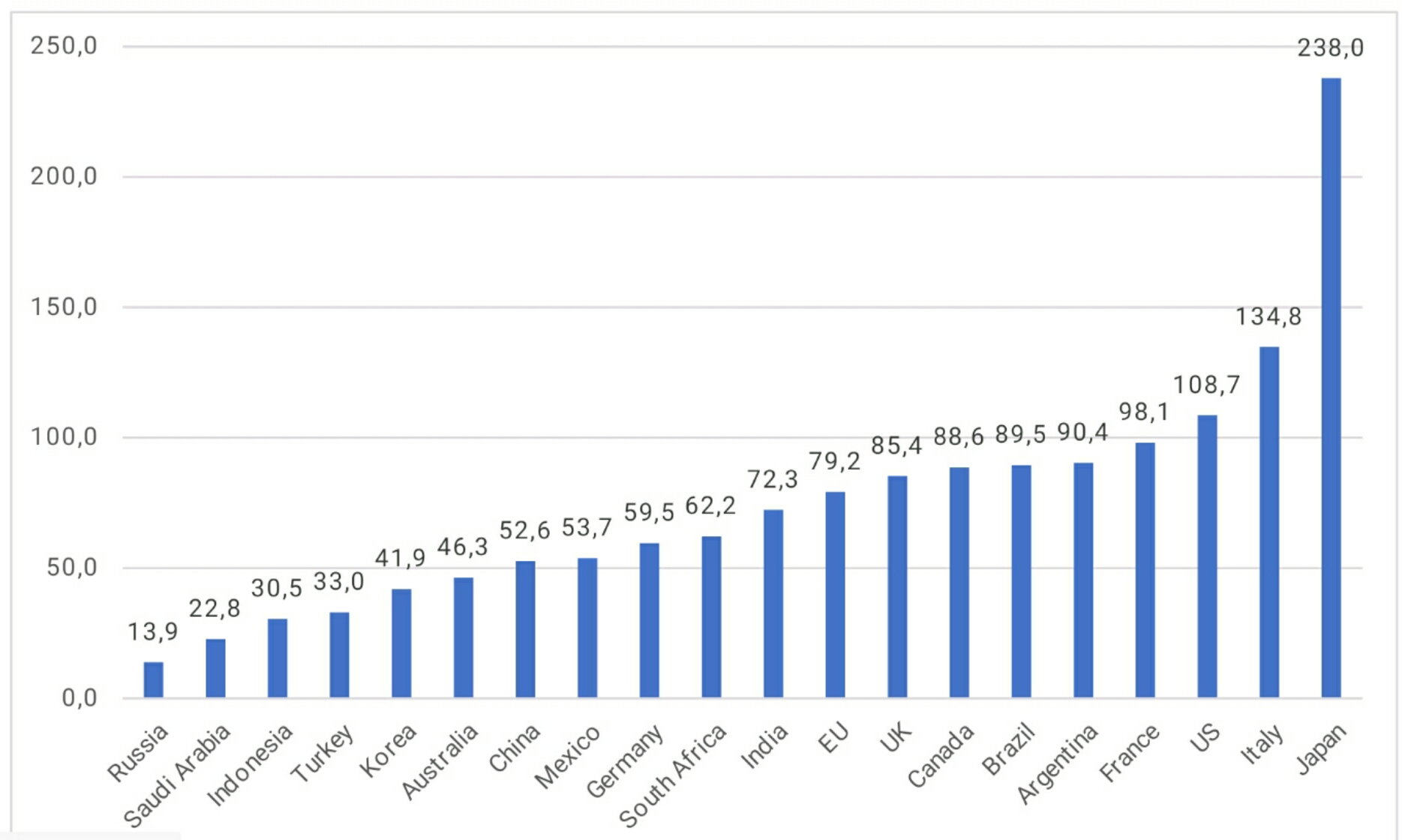

Figure 3: General government gross public debt in G20 economies, % GDP, 2019

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2020

Everybody understands that there is an upper limit of economic losses that a given economy can accept. Usually this limit is lower in developing economies in which the choice between protecting people from the pandemic and guaranteeing them a minimal living standard looks dramatic (Basu, 2020). However, the macroeconomic situation in most high- and middle-income countries is also difficult. They entered the COVID-19 crisis with high public debt (see Figure 3) and without fiscal reserves for ‘rainy’ days. As a result, they reached limits of their GDP losses and costs of government intervention quickly.

Thus, it is not surprising that after the strict lockdowns in the first half of 2020 individual countries started to reopen their economies. Accumulated knowledge on the pandemic has given hope that more selective measures of a ‘soft’ or ‘smart’ lockdown will be sufficient to contain pandemic with smaller economic costs. However, the new outburst of pandemic on the Northern Cone in September and October 2020 puts these hopes under big questions.

The nature of the crisis

Beyond the fundamental choice between public health and economic considerations, the crisis management process has been confronted with the necessity to rightly diagnose the macroeconomic character of the crisis. Most governments and central banks in high-income economies reacted in a similar way as during the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009 – by aggressive monetary and fiscal easing. Such a reaction assumes that the crisis related shock has a demand-side character. Indeed, this was the case of GFC when a deep financial disintermediation caused a powerful deflationary shock.

The characteristic of the current crisis is different. It is a combination of demand-side and supply-side shock, resulting mainly from restriction measures. In such circumstances, private spending decreases and private savings increase, but these are forced savings, similarly to centrally-planned economies where people could not spend their income on the goods and services they wanted to buy because they were not available.

In terms of monetary arithmetic, forced savings mean additional demand for money balances, which creates a kind of temporary buffer against the increased supply of money caused by monetary and fiscal expansion. The key questions are how big this monetary overhang is, and how quickly it will disappear once pandemic ends. At the moment, nobody knows the exact answers to these questions because demand for money is not stable in the time of crisis. It can change dramatically in a short period of time, as a reaction to factors unknown and unpredictable today. The increase of assets prices in 2020, after short decline of stock indexes in February and March 2020 (The Economist, 2020) suggests that monetary overhang may be quite substantial

Deterioration of fiscal position is, to some extent, unavoidable because government revenue declines as a result of recession and various kinds of spending (for fighting the pandemic, strengthening public health systems, social protection of the most vulnerable, compensation for business for lockdown measures, etc.) increase. One can say that these are automatic fiscal stabilizers in work and they are less controversial. A more controversial is discretionary fiscal stimulus to boost aggregate demand. It may raise several questions: on the available fiscal space to launch such stimulus, its timing, concrete design and potential fiscal multipliers.

As already mentioned, in most high-income economies, the fiscal space is rather limited and the unknown length of pandemic makes it difficult to assess its safe size. In middle- and low-income economies the fiscal space is even more limited, except perhaps some oil producers who managed to accumulate fiscal reserves in the past.

The question of timing is directly related to the above-discussed characteristic of the current crisis. If economic agents cannot spend because of administrative restrictions or uncertainty related to the length and intensity of pandemic what is the rationale to increase their spending power by means of fiscal or monetary policies? Perhaps it makes sense to wait until the end of pandemic (and related containment measures) to launch monetary and fiscal stimulus to accelerate the recovery phase?

Designing a stimulus package, policymakers must decide not only on its size but also on its structure and choice of concrete instruments. For example, what should be given priority - additional spending programs or revenue measures (tax cuts)? This leads us to the next important question – whom to protect?

Whom to rescue – enterprises or individuals?

The pandemic-related shock and lockdown forced governments to offer people and businesses financial compensation. The concrete forms of these ‘protection shields’ differ between countries depending on local circumstances, including available fiscal space, and policymakers’ preferences. The most principal choice is between protecting people directly or protecting them by supporting enterprises, in which they are employed.

The first approach has dominated so far in the United States where, in addition to unemployment benefits, the federal government has offered, among others, the one-off Economic Impact Payments to all individuals whose annual income was below USD 99,000 in 2019 and all children under 17 years old, and the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfers to school-age children. The support to businesses has been relatively limited. The second approach, that is, offering companies in the most crisis-affected sectors various kinds of financial aid (for example, tax exemptions, forgiveness, or temporary suspension of tax obligation, special loans, etc.), usually under condition of avoiding layoffs of their employees, has dominated in Europe.

The rationale of each approach depends on labor market flexibility in a given economy (it is higher in the US than in Europe) and on assumptions regarding crisis length and its long-term economic impact. When in Spring 2020 one might expect that it would be a short-term episode a policy aimed at protection of existing enterprises and their employment seemed justified because it could facilitate a rapid recovery when the pandemic ends. However, this assumption must be corrected. Now we know that the crisis will last longer and may bring substantial structural changes. Think about rapid expansion of digital services, e-commerce, e-banking, on-line education, telework, etc. On the other hand, business trips, conferences and congresses, traditional retail, demand for commercial real estate and office space, etc. may shrink for good. Some other sectors like tourism, hospitality or air travel may experience declining demand for a longer period of time.

Under such a scenario, protection of existing capacities may be counterproductive. It can lead to the phenomenon of zombie firms without market prospects but artificially supported by taxpayers. Therefore, it is better to allow market allocation mechanisms to work, including a Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’, and provide a temporary social protection to people who will have to change their jobs and professions.

In practice, however, both approaches will be needed because economic policy will have to deal with a combination of temporary slump (caused by the pandemic and associated lockdown) and durable structural changes.

References

Basu, Kaushik (2020): Who’s Afraid of COVID-19, Project Syndicate, May 6,

The Economist (2020): The three pillars: Why despite the coronavirus pandemic, house prices continue to rise, The Economist, September 30