Norms and Values

BRICS Expansion as Non-West Consolidation? The Example of Voting in the UN General Assembly

© Sputnik

In the context of the UN General Assembly, the euphemism “collective West” gets its clear quantitative expression. As the resolutions of recent years on Russia and Iran have shown, our geopolitical opponents always have at least 60 votes in the General Assembly, writes Valdai Club Programme Director Oleg Barabanov.

The expamsion of the BRICS and the announced admission of six new states to the group has become an important event in world politics. About two dozen more countries have also applied to join the BRICS. In this regard, the media and the expert community have begun to talk about a qualitative change in the geopolitical balance of power. Comparisons are made between the BRICS and the G7 in terms of their GDP, resources etc. All this is true. But aside from economic indicators and symbolic strength as a value alternative, the issue of internal consolidation is no less important for the political power of any international structure.

BRICS is no exception. If there is no internal unity based on “all for one and one for all”, then all prospects for strengthening the BRICS as a new pole of world politics will remain unfulfilled.

One of the most obvious, albeit not the most important, indicators of this internal political consolidation is the example of voting in the UN General Assembly. We have previously reviewed these votes, focusing on African countries differing in their reaction to resolutions on Russia and Ukraine in 2022-23. Naturally, the results of these votes should not be absolutised. There is not always a direct connection between the vote of a country in the UN and its real willingness to cooperate with Russia. There are many different factors. Also in Africa, the lists of countries that never voted against Russia in the UN General Assembly in 2022-23 and the lists of presidents who came to the second Russia-Africa Summit in the summer of 2023 were about two-thirds similar. It’s a lot, but not one hundred percent.

However, the level of internal consolidation of a particular structure is also determined by a unified approach to voting on international platforms. This is clearly seen in the example of NATO and the EU, whose member countries in the UN General Assembly, as a rule, vote in the same way. In our opinion, it is interesting to see how the “old” and new members of the BRICS behave in this regard. A whole series of resolutions has been adopted in the UN General Assembly over the last several years regarding Russia and Iran. Let’s look at the results of voting on them by the BRICS states.

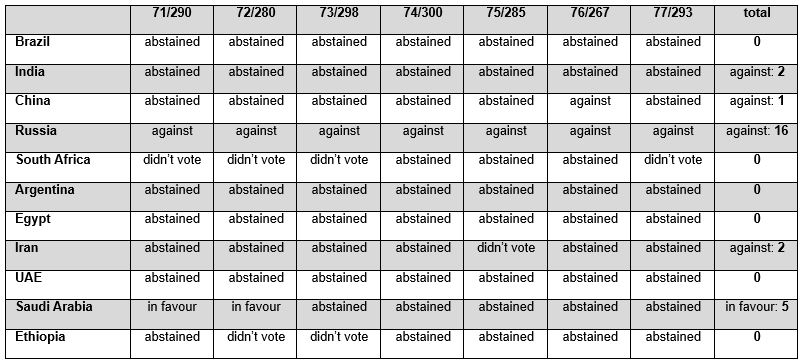

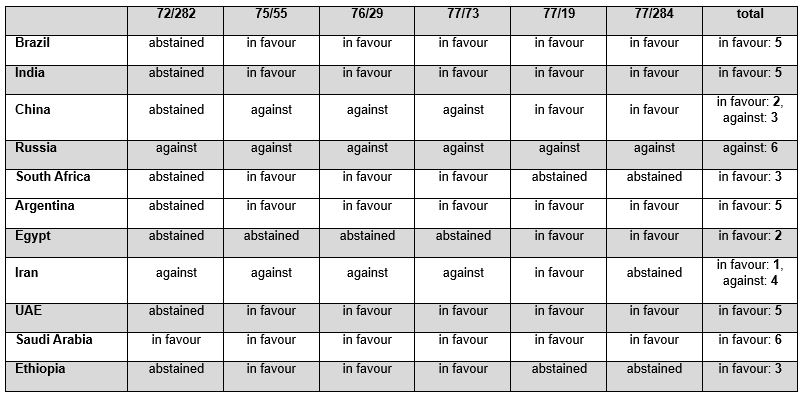

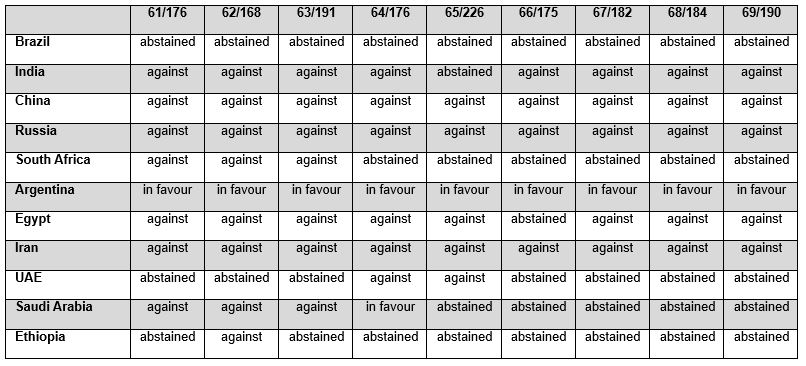

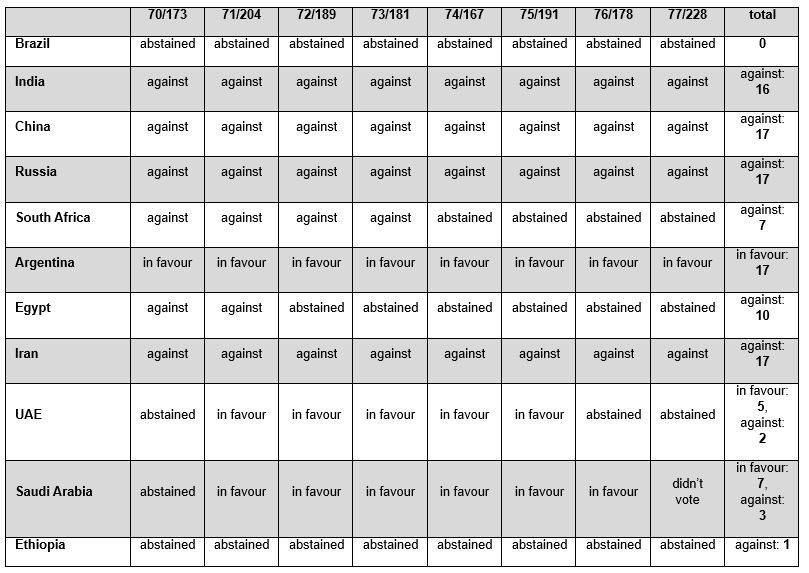

In each of the following tables: abst. — abstained, withheld — did not vote. The final column summarises the votes for and against for each country. If the state abstained or did not vote all the time, then the result is zero.

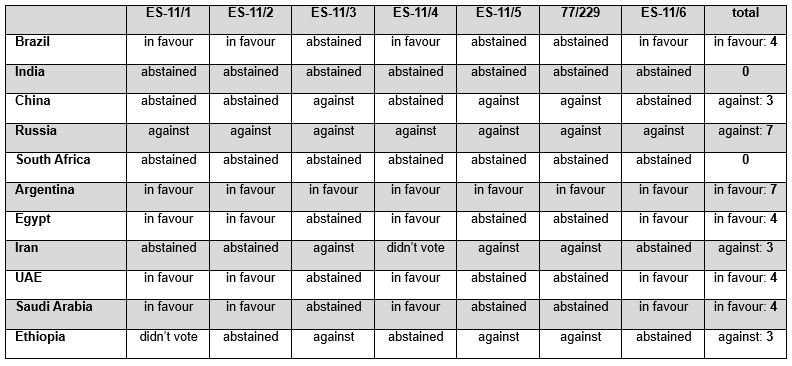

UNGA resolutions against Russia after Feb. 24, 2022:

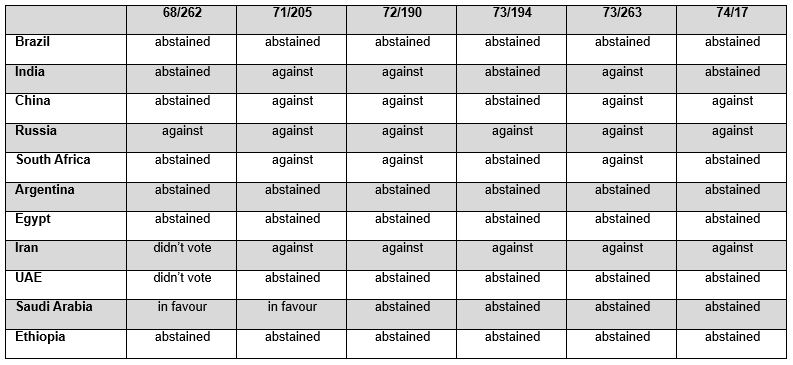

Resolutions of the UN General Assembly on Crimea before Feb. 24, 2022:

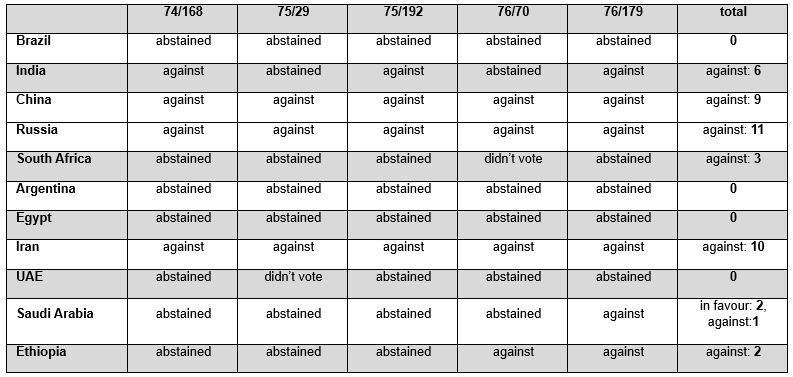

Resolutions of the UN General Assembly on South Ossetia and Abkhazia (the first resolution of the UN General Assembly, only on Abkhazia, was adopted in May 2008, even before the armed conflict in August 2008. Since thenthe resolutions are adopted annually, and since 2009 South Ossetia has been included):

Other UNGA resolutions condemning Russia:

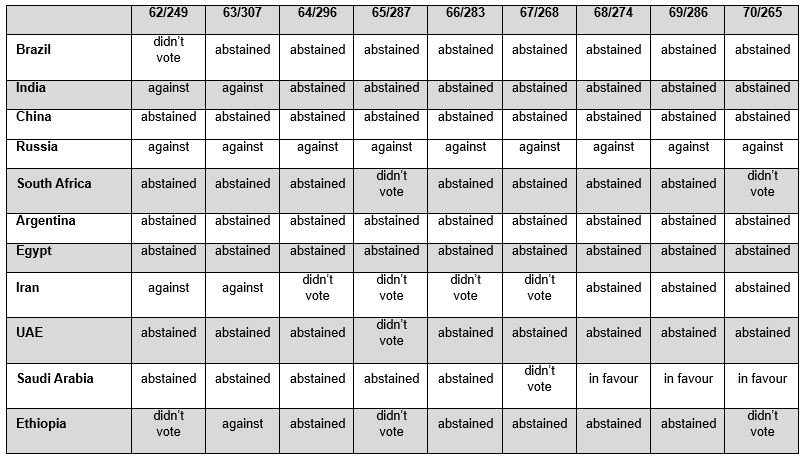

The UNGA resolutions on Iran (resolutions on human rights in Iran, since 1985, have been adopted by the UNGA almost every year. This selection includes votes since 2006, the year of the first BRIC ministerial meeting):

The results of these votes can be assessed as follows. In relation to Russia, before the incident with Alexei Navalny and before February 24, 2022, the “old” BRICS members never voted for anti-Russian resolutions. But there has never been unanimous support for Russia or a vote against such resolutions.

On Crimea, by February 24, 2022, 11 resolutions were adopted, in 2014-21. Russia itself, of course, voted against all of them. China was closest to Russia in its position; it voted “against” 9 times out of 11. China abstained twice: on the very first resolution in 2014 on the territorial integrity of Ukraine, as well as on the first resolution on the militarization of Crimea in 2018, adopted after the military maritime incident in the Kerch Strait. India voted against 6 times out of 11. It abstained on the first 2014 resolution on territorial integrity, as well as on all 4 resolutions on the 2018-21 militarisation of Crimea. India voted against all the 6 resolutions on human rights in Crimea (which the UN General Assembly began to adopt almost annually starting in 2016, following the prohibition of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis in Russia). South Africa voted no to resolutions 3 times and Brazil abstained all the time. It should also be noted that according to the very first resolution of 2014 on the territorial integrity of Ukraine, no one from the “old” BRICS members, except Russia itself, voted against this resolution. All chose to abstain.

Since 2008, a total of 16 resolutions have been adopted on Abkhazia and South Ossetia; 14 of them before February 24, 2022 and two after. Here it must be pointed out that none of them mentioned Russia, and they were written in Aesopian and, in a sense, soft language. This, of course, made them easier to accept. As a result, many UN member states were not interested in these resolutions, and especially at first the vast majority of countries abstained or did not vote. The very first resolution on Abkhazia in May 2008, adopted even before the August conflict of that year, in general, most likely, can be a record holder for disinterest. A paltry 14 states voted in favour, 11 against, and all the rest of the then 192 UN members either abstained (105 countries) or did not vote at all (62). Of course, according to the normative provisions of the General Assembly, it is not necessary that the number of votes “in favour” exceed 50% of the total number of members. It is sufficient that any number of “in favour” votes exceed the number of “against” votes. The logic here is that the resolution is adopted by those who are interested in it, and those who are not interested in the subject of the resolution in any way are not taken into account. As a result, a fairly large number of UNGA resolutions are adopted by a majority that constitutes fewer than 50% of the member countries. It is not uncommon for resolutions to be adopted with 80 or even 60 votes “in favour” out of 193 member countries, but the first Abkhazian resolution, adopted with only 14 votes, is most likely the absolute record holder here.

According to this logic, the “old” BRICS members also tended to abstain on the Abkhaz-South Ossetian resolutions, and showed much less unanimity with Russia than on the Crimean resolutions. Russia itself, although it was not directly mentioned in the text of the resolutions, of course, voted against all 16 of them. India voted “against” twice (both times before February 24, 2022), China cast one no vote (after February 24, 2022), and South Africa and Brazil always abstained or did not vote.

According to the only resolution of 2018 on the withdrawal of foreign troops from Moldova, the situation was similar. Russia voted against it, while all other “old” BRICS members abstained.

The situation changed after the incident with the alleged poisoning of Alexei Navalny in 2020. Almost every year, the UN General Assembly adopts resolutions in support of the implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention. In the 2010s, their focus was mainly on Syria. The Skripal poisoning incident in 2018 was reflected in these resolutions, but in the same Aesopian language, without mentioning Russia, as in the case of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It was only about the “use of chemical weapons in the UK”. Russia, of course, voted against these resolutions, the rest — no matter what. But Russia was only mentioned after the incident with the poisoning of Alexei Navalny; its “condemnation in the most decisive way” was included in the texts of the resolutions, and not even in the preamble, but in the operative part. And here the majority of the “old” BRICS members had already stopped abstaining and started voting for these resolutions. It is clear that Russia was only one of the points in a fairly large text by UN standards. And for three of the four “old” BRICS members (not counting Russia itself), it was obviously more important to show their solidarity with the global “fight” to ban chemical weapons than to demonstrate solidarity with Russia.

As a result, three resolutions were adopted on chemical weapons with the mention of Alexei Navalny and the condemnation of Russia in 2020-22, two before 24 February 2022 and one after. Russia voted against all three. China is also against all three. India, Brazil and South Africa voted in favour of all three resolutions.

The expamsion of the BRICS and the announced admission of six new states to the group has become an important event in world politics. About two dozen more countries have also applied to join the BRICS. In this regard, the media and the expert community have begun to talk about a qualitative change in the geopolitical balance of power. Comparisons are made between the BRICS and the G7 in terms of their GDP, resources etc. All this is true. But aside from economic indicators and symbolic strength as a value alternative, the issue of internal consolidation is no less important for the political power of any international structure.

BRICS is no exception. If there is no internal unity based on “all for one and one for all”, then all prospects for strengthening the BRICS as a new pole of world politics will remain unfulfilled.

One of the most obvious, albeit not the most important, indicators of this internal political consolidation is the example of voting in the UN General Assembly. We have previously reviewed these votes, focusing on African countries differing in their reaction to resolutions on Russia and Ukraine in 2022-23. Naturally, the results of these votes should not be absolutised. There is not always a direct connection between the vote of a country in the UN and its real willingness to cooperate with Russia. There are many different factors. Also in Africa, the lists of countries that never voted against Russia in the UN General Assembly in 2022-23 and the lists of presidents who came to the second Russia-Africa Summit in the summer of 2023 were about two-thirds similar. It’s a lot, but not one hundred percent.

However, the level of internal consolidation of a particular structure is also determined by a unified approach to voting on international platforms. This is clearly seen in the example of NATO and the EU, whose member countries in the UN General Assembly, as a rule, vote in the same way. In our opinion, it is interesting to see how the “old” and new members of the BRICS behave in this regard. A whole series of resolutions has been adopted in the UN General Assembly over the last several years regarding Russia and Iran. Let’s look at the results of voting on them by the BRICS states.

In each of the following tables: abst. — abstained, withheld — did not vote. The final column summarises the votes for and against for each country. If the state abstained or did not vote all the time, then the result is zero.

UNGA resolutions against Russia after Feb. 24, 2022:

- ES-11/1 of March 2, 2022 First resolution after the start of the conflict. Characterisation of the actions of the Russian Federation as “aggression against Ukraine”;

- ES-11/2 of 24 March 2022 Humanitarian consequences of the conflict;

- ES-11/3 of April 7, 2022 Suspension of the membership of the Russian Federation in the UN Human Rights Council;

- ES-11/4 of October 12, 2022 Territorial integrity of Ukraine (after referendums on the entry of four new subjects into the Russian Federation);

- ES-11/5 of November 14, 2022 Compensation and reparations to Ukraine;

- 77/229 of December 15, 2022 Human rights in Crimea;

- ES-11/6 of 23 February 2023 Principles of the UN Charter underpinning the achievement of a comprehensive, just and lasting peace in Ukraine. Adopted on the anniversary of the conflict.

Resolutions of the UN General Assembly on Crimea before Feb. 24, 2022:

- 68/262 of March 27, 2014 “Territorial Integrity of Ukraine”;

- resolution on human rights in Crimea: 71/205 of 19 December 2016; 72/190 of December 19, 2017; 73/263 dated December 22, 2018; 74/168 of December 18, 2019; 75/192 of December 16, 2020; 76/179 of December 16, 2021;

- resolutions on the Crimean militarisation: 73/194 of December 17, 2018; 74/17 of December 9, 2019; 75/29 of December 7, 2020; 76/70 of December 9, 2021;

Resolutions of the UN General Assembly on South Ossetia and Abkhazia (the first resolution of the UN General Assembly, only on Abkhazia, was adopted in May 2008, even before the armed conflict in August 2008. Since thenthe resolutions are adopted annually, and since 2009 South Ossetia has been included):

- resolution 62/249 of April 15, 2008 on the status of internally displaced persons and refugees from Abkhazia (excluding South Ossetia);

- resolutions on the situation of internally displaced persons and refugees from Abkhazia and South Ossetia:

- 63/307 of September 9, 2009; 64/296 of September 7, 2010; 65/287 of June 29, 2011; 66/283 of July 3, 2012; 67/268 of June 13, 2013; 68/274 of June 5, 2014; 69/286 of June 3, 2015; 70/265 of June 7, 2016; 71/290 of June 1, 2017; 72/280 of June 12, 2018; 73/298 of June 4, 2019; 74/300 of September 3, 2020; 75/285 of June 16, 2021; 76/267 of June 18, 2022; 77/293 of June 7, 2023.

Other UNGA resolutions condemning Russia:

- 72/282 of June 22, 2018 “Full and unconditional withdrawal of foreign armed forces from the territory of the Republic of Moldova”; the resolution on chemical weapons and Alexei Navalny: 75/55 of December 7, 2020 “Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition in Favour of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction”. In the operative part in paragraph 2 of the GA, it “condemns in the strongest possible way the fact that a toxic chemical was used in the Russian Federation as a weapon against Alexei Navalny.” Similar resolutions: 76/29 of December 6, 2021 (paragraph 2 of the operative part); 77/73 of December 7, 2022 (paragraph 2 of the operative part);

- 77/19 of November 21, 2022 “Cooperation between the UN and the Central European Initiative”. Both in the preamble and in the operative part (p. 3) the “aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine” is mentioned;

- 77/284 of April 26, 2023 “Cooperation between the UN and the Council of Europe”, where the preamble mentions “the aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, and before that against Georgia” and that cooperation between the UN and the Council of Europe needs to be strengthened “in order to promptly restore ... peace and security on the basis of respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity, ... repair the damage caused to the victims and hold accountable all those who are guilty of violating the norms of international law.”

The UNGA resolutions on Iran (resolutions on human rights in Iran, since 1985, have been adopted by the UNGA almost every year. This selection includes votes since 2006, the year of the first BRIC ministerial meeting):

- resolution on human rights in Iran: 61/176 of December 19, 2006; 62/168 of December 18, 2007; 63/191 of December 18, 2008; 64/176 of December 18, 2009; 65/226 of December 21, 2010; 66/175 of December 19, 2011; 67/182 of December 20, 2012; 68/184 of December 18, 2013; 69/190 of December 18, 2014; 70/173 of December 17, 2015; 71/204 of December 19, 2016; 72/189 of December 19, 2017; 73/181 of December 17, 2018; 74/167 of December 18, 2019; 75/191 of December 16, 2020; 76/178 of December 16, 2021; 77/228 of December 15, 2022.

The results of these votes can be assessed as follows. In relation to Russia, before the incident with Alexei Navalny and before February 24, 2022, the “old” BRICS members never voted for anti-Russian resolutions. But there has never been unanimous support for Russia or a vote against such resolutions.

On Crimea, by February 24, 2022, 11 resolutions were adopted, in 2014-21. Russia itself, of course, voted against all of them. China was closest to Russia in its position; it voted “against” 9 times out of 11. China abstained twice: on the very first resolution in 2014 on the territorial integrity of Ukraine, as well as on the first resolution on the militarization of Crimea in 2018, adopted after the military maritime incident in the Kerch Strait. India voted against 6 times out of 11. It abstained on the first 2014 resolution on territorial integrity, as well as on all 4 resolutions on the 2018-21 militarisation of Crimea. India voted against all the 6 resolutions on human rights in Crimea (which the UN General Assembly began to adopt almost annually starting in 2016, following the prohibition of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis in Russia). South Africa voted no to resolutions 3 times and Brazil abstained all the time. It should also be noted that according to the very first resolution of 2014 on the territorial integrity of Ukraine, no one from the “old” BRICS members, except Russia itself, voted against this resolution. All chose to abstain.

Since 2008, a total of 16 resolutions have been adopted on Abkhazia and South Ossetia; 14 of them before February 24, 2022 and two after. Here it must be pointed out that none of them mentioned Russia, and they were written in Aesopian and, in a sense, soft language. This, of course, made them easier to accept. As a result, many UN member states were not interested in these resolutions, and especially at first the vast majority of countries abstained or did not vote. The very first resolution on Abkhazia in May 2008, adopted even before the August conflict of that year, in general, most likely, can be a record holder for disinterest. A paltry 14 states voted in favour, 11 against, and all the rest of the then 192 UN members either abstained (105 countries) or did not vote at all (62). Of course, according to the normative provisions of the General Assembly, it is not necessary that the number of votes “in favour” exceed 50% of the total number of members. It is sufficient that any number of “in favour” votes exceed the number of “against” votes. The logic here is that the resolution is adopted by those who are interested in it, and those who are not interested in the subject of the resolution in any way are not taken into account. As a result, a fairly large number of UNGA resolutions are adopted by a majority that constitutes fewer than 50% of the member countries. It is not uncommon for resolutions to be adopted with 80 or even 60 votes “in favour” out of 193 member countries, but the first Abkhazian resolution, adopted with only 14 votes, is most likely the absolute record holder here.

According to this logic, the “old” BRICS members also tended to abstain on the Abkhaz-South Ossetian resolutions, and showed much less unanimity with Russia than on the Crimean resolutions. Russia itself, although it was not directly mentioned in the text of the resolutions, of course, voted against all 16 of them. India voted “against” twice (both times before February 24, 2022), China cast one no vote (after February 24, 2022), and South Africa and Brazil always abstained or did not vote.

According to the only resolution of 2018 on the withdrawal of foreign troops from Moldova, the situation was similar. Russia voted against it, while all other “old” BRICS members abstained.

The situation changed after the incident with the alleged poisoning of Alexei Navalny in 2020. Almost every year, the UN General Assembly adopts resolutions in support of the implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention. In the 2010s, their focus was mainly on Syria. The Skripal poisoning incident in 2018 was reflected in these resolutions, but in the same Aesopian language, without mentioning Russia, as in the case of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It was only about the “use of chemical weapons in the UK”. Russia, of course, voted against these resolutions, the rest — no matter what. But Russia was only mentioned after the incident with the poisoning of Alexei Navalny; its “condemnation in the most decisive way” was included in the texts of the resolutions, and not even in the preamble, but in the operative part. And here the majority of the “old” BRICS members had already stopped abstaining and started voting for these resolutions. It is clear that Russia was only one of the points in a fairly large text by UN standards. And for three of the four “old” BRICS members (not counting Russia itself), it was obviously more important to show their solidarity with the global “fight” to ban chemical weapons than to demonstrate solidarity with Russia.

As a result, three resolutions were adopted on chemical weapons with the mention of Alexei Navalny and the condemnation of Russia in 2020-22, two before 24 February 2022 and one after. Russia voted against all three. China is also against all three. India, Brazil and South Africa voted in favour of all three resolutions.

BRICS has received an impulse to make a real transition to a new, more just world order. The ability of the new BRICS to fully realize itself and fulfill the mission of the transition depends on how our descendants will remember the 21st century, Viktoria Panova writes.

Opinions

This situation developed after February 24, 2022. The General Assembly has so far adopted seven resolutions condemning Russia over Ukraine. One of them, the annual resolution on human rights in Crimea, was adopted in the usual format, at an ordinary session of the UN General Assembly. Six resolutions were adopted at the specially convened 11th emergency session of the UN General Assembly. These emergency sessions, in accordance with the normative provisions of the General Assembly, may be held in exceptional cases of a threat to peace. Previously, the Soviet Union had been the subject of such sessions: the second emergency session of the UN General Assembly in 1956-57 for Hungary and the sixth session in 1980 for Afghanistan.

Most often, such sessions focus on Israel and Middle East-related problems (the first emergency session was in 1956 amid the Suez crisis, the third was held in 1958 amid the Lebanese crisis, the fifth in 1967 amid the Six Day War, the seventh in 1980-82 to address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the ninth in 1982 for the Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights and the tenth in 1997-2018, again to address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict). Another emergency session of the UN General Assembly was devoted to the crisis in the Congo (the fourth, in 1960), and one to the occupation of Namibia by South Africa (the eighth, in 1981). The very format of emergency sessions may, to some extent, imply a special responsibility of states when voting in the fight against a threat to peace. Perhaps this logic, somewhat similar to the situation described above with global solidarity in the fight against chemical weapons, could have influenced the voting among the “old” BRICS members, among other substantive factors. But whether it is true or not, here we also see examples of support by one of the “old” BRICS members for these resolutions.

In addition to the “ordinary” annual resolution on human rights in Crimea, where China voted against and the rest abstained, we see such a picture in the resolutions of the emergency session. Of these six resolutions, China twice voted against (on the suspension of Russia’s membership in the Council for Human Rights and Reparations), and abstained in other cases. India and South Africa have always abstained. Brazil voted in favour of the emergency session resolutions four times and abstained twice.

In addition to these seven resolutions, where Russia was directly in focus, the phrase about “Russian aggression against Ukraine” was included in two more resolutions of the UN General Assembly. The General Assembly periodically adopts resolutions on cooperation between the UN and various regional organisations, and also extends them from time to time. Accordingly, two such resolutions adopted after February 24, 2022 included this phrase: in November 2022 on UN cooperation with the Central European Initiative (both in the preamble and in the operative part), and in April 2023 on UN cooperation with the Council of Europe (in the preamble).

In both cases, there were also examples of votes “for” among the “old” BRICS members. The first of these resolutions passed quite quietly in the media of Russia, and the second caused a rather tangible response, due to the fact that Russia’s partners voted for a document where Russia is accused of aggression. In response, it was also said in our media field that this resolution itself has nothing to do with Russia, that it is only a phrase in the preamble, and it was not necessary to pay attention. The logic of such a vote here may also be similar to the aforementioned vote on chemical weapons. Solidarity with the activities of European regional organisations (the main subject of the resolutions) turned out to be higher than solidarity with Russia. In any case, only South Africa abstained both times, while China, India and Brazil voted in favour of both of these resolutions.

Now let’s move on to the new members of the BRICS. On the Crimean resolutions before February 24, 2022, Iran voted 10 times out of 11 against, Ethiopia 2 times, Argentina, Egypt and the UAE always abstained or did not vote, and Saudi Arabia voted yes twice (in 2014-16) and once against (in 2021). On Abkhazia and South Ossetia, out of 16 resolutions, Iran twice voted against, Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt and the UAE always abstained or did not vote, and Saudi Arabia voted in favour five times. Regarding Moldova, Saudi Arabia was in favour, Iran was against, and the rest abstained or did not vote.

On chemical weapons and Navalny: Argentina, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia all voted three times in favour, Iran voted all three times against, and Egypt abstained every time. On the seven resolutions regarding the conflict with Ukraine: Argentina voted in favour of all seven; Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia voted four times in favour, and Iran and Ethiopia voted three times against them. On the two resolutions on cooperation with European organisations: Argentina, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia voted “for” both times, Iran voted once “for”, and Ethiopia abstained both times.

Summing up, in 2008-2023, the UN General Assembly adopted 40 more or less anti-Russia resolutions. Russia voted against them all 40 times. Iran voted against them 19 times and once time “for”, China voted 16 times “against” and twice “for”, India voted 8 times “against” and 5 “for”, Ethiopia voted 5 times “against” and 3 times “for”, South Africa voted three times “against” and three times “for”, Egypt voted 6 times “for”, Brazil voted 9 times “for”, the UAE also voted “for” 9 times, Argentina voted “for” 12 times, Saudi Arabia voted “for” 17 times and once against.

Let us repeat once again, it is clear that there is no absolutely direct connection between voting in the UN and real cooperation of certain countries with Russia. We saw this in the aforementioned example of African states. And BRICS itself is developing constructively and effectively. If it were not so, then more than two dozen states would not seek to get there. But in the context of the UN battles, the “old” and new BRICS countries can be divided into four groups:

- Iran and China, in about half of all cases, vote in solidarity with Russia;

- India and Ethiopia have a slight majority of votes for Russia over votes against it, while South Africa has an equal balance, but most often these countries abstain;

- Egypt, Brazil and the UAE abstain about three-quarters of the time and vote against Russia about one-quarter of the time;

- Argentina and Saudi Arabia most often vote against Russia.

In addition to Russia, from the enlarged BRICS, Iran is also a target of UN General Assembly resolutions. Since 1985, resolutions on human rights in Iran have been adopted there almost every year. During the period considered here since 2006, 17 resolutions have been adopted on Iran. Iran itself voted against them all 17 times. Russia and China have also voted against 17 times, India 16 against, Egypt 10 against, South Africa 7 against, Ethiopia once against, Brazil has always abstained, and the UAE has voted in favour five times and twice against. Saudi Arabia has voted “for” 7 times and “against” 3 times. Finally, Argentina voted for the anti-Iranian resolutions all 17 times.

Here we note that, unlike the resolutions on Russia, in the case of Iran, there are three examples from the “old” BRICS members voting 99-100% in absolute solidarity with Iran. These are Russia, China and India. At the same time, one of the new BRICS members takes a categorically anti-Iranian position. It isn’t even one of the Arab states of the Gulf, as one might think, but Argentina, far from Iran.

In general, we note again that the obtained numbers should not be absolutised. But at the same time, in the context of the UN General Assembly, the euphemism “collective West” gets its clear quantitative expression. As the resolutions of recent years on Russia and Iran have shown, our geopolitical opponents always have at least 60 votes in the General Assembly. As noted above, taking into account the fact that the adoption of a resolution by the UN General Assembly does not require that the number of votes “for” exceed 50% of the UN member countries, then almost all resolutions in favour of Western countries are adopted by the Assembly. By and large, there are no reverse cases, if you do not include the anti-Israeli resolutions, the American embargo on Cuba, and the new topic (though, unfortunately, it has become, apparently, a one-time affair) — the decolonisation of the Chagos Archipelago.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has already publicly drawn attention to the situation when Western countries most often vote with a single voice, in fact, with bloc discipline; while in response there is only confusion and vacillation and there is no single solidarity vote on the part of the EAEU and the CSTO. As we can see, this is also true for the BRICS. It is clear that the principle here is that Non-West is not always equal to Anti-West, and not all non-Western countries have the same level of radicalism and revisionism in this matter. This is all understandable and, I think, there is no reason to believe that this situation will qualitatively change in the medium term. But without this, the question of the consolidation of the Non-West, which has re-emerged in connection with the expansion of the BRICS, hangs in the air. In any case, the Non-West will always get pro-Western resolutions in the UN General Assembly.

The bloc was dismissed by many in the beginning, with some arguing that it does not hold sufficient power to change anything, let alone contend with the global hegemons. But BRICS is not about challenging anyone. It is about fostering cooperation and collaboration to find solutions for global challenges and achieve a shared future in which development is enhanced and accessible to all who seek it, Mikatekiso Kubayi writes.

Opinions

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.