Washington’s policy of containing China gives Vietnam an opportunity of historic proportions. Today, as globalization as we knew it unravels, some states receive privileges “just for being there,” and Vietnam’s leadership cannot afford to the miss the development opportunities opening up for the nation of 100 million people. Risks are high as well, and the end result depends on skill of the helmsmen navigating between the great powers’ conflicting interests, writes Anton Bespalov, valdaiclub.com Deputy Editor-in-Chief.

This week saw Chinese President Xi Jinping make a state visit to Vietnam. The two countries reaffirmed their strategic partnership and agreed to build “a community with a shared future.” This was preceded by debate on the exact wording: Vietnamese diplomats insisted that the Chinese term, literally meaning “community of common destiny” should sound more neutral in English and Vietnamese. Vietnam also supported the Chinese idea of building a community with a shared future for mankind, the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilisation Initiative. All of these align to varying degrees with the Russian vision of a multipolar world and are seen in the West as a challenge to the US-led “rules-based order.”

Only three months ago, Hanoi welcomed US President Joe Biden, who arrived on an official visit and signed a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement with Vietnam, a crucial milestone for the country. Vietnam first floated the idea back in 2011, but it did not materialize under either Obama or Trump. Notably, Vietnam is the only country to have been visited by both Biden and Xi this year, an indication of its importance for the leading centres of power, but also of its ability to deal with all actors.

The Vietnamese foreign policy style was labelled “bamboo diplomacy.” According to the official interpretation, the country’s diplomacy “resembles Vietnamese bamboo, which has strong roots, a firm trunk, and flexible branches.” Indeed, it has demonstrated a lot of firmness and flexibility in recent years. Hanoi’s main ambition is to strengthen its positions amid the unfolding great power confrontation, which is fraught with obvious dangers but also opens new development opportunities.

Vietnam is a classic “medium power” capable of influencing international politics to a certain degree and being a regional centre of power. It ranks third in ASEAN by population (100 million) and GDP (PPP) – almost $1.5 billion. According to the Global Firepower rating, it is the second strongest military power in ASEAN.

The reform policy initiated in 1986 made Vietnam one of the “tiger cub economies,” which continues to demonstrate stable growth (4.24% in 2023, so far). Its GDP (PPP) per capita has grown eightfold over the past twenty years. However, the World Bank still rates it as a lower-middle income economy. Vietnam joined this category in 2009 and is now poised to become upper-middle income. Remarkably, China had completed this journey by 2010, so the widespread characterisation of Vietnam as “China a dozen years ago” is not ungrounded.

As the world is going through the unravelling of globalisation as we knew it, countries like Vietnam are doing their utmost to seize still-available opportunities. Its relatively cheap workforce gives Vietnam a competitive edge against China, where the cost of labour continues to grow. The country, which used to be predominantly agrarian, is now one of Asia’s “assembly shops.” The electronic industry has been booming since the late 2000s, with Samsung Electronics contributing a quarter to Vietnam’s exports.

At the same time, it is clear that the country cannot always be satisfied with its “assembly shop” role and needs a higher place in global value chains. For years, the dependence of the economy on foreign direct investment (with the FDI sector accounting for more than three quarters of total export turnover) has been a major concern for Vietnamese experts. The government is taking measures to rectify this distortion by strengthening the production and export capabilities of domestic companies so that they can play a bigger role in the economy and encouraging private enterprises to expand into the manufacturing and high-tech sectors to strengthen Vietnam’s domestic industrial base.

Accounting for $109 billion in exports (29% of the total), the United States is Vietnam’s largest export market, followed by China (16%). In 2022, Vietnam became the sixth largest exporter to the United States and is seen by many as the biggest beneficiary of the US-China decoupling. As for Vietnamese imports, almost a third originates from China (40% with Hong Kong) followed by South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan (collectively, East Asian states account for 59% of Vietnam’s imports).

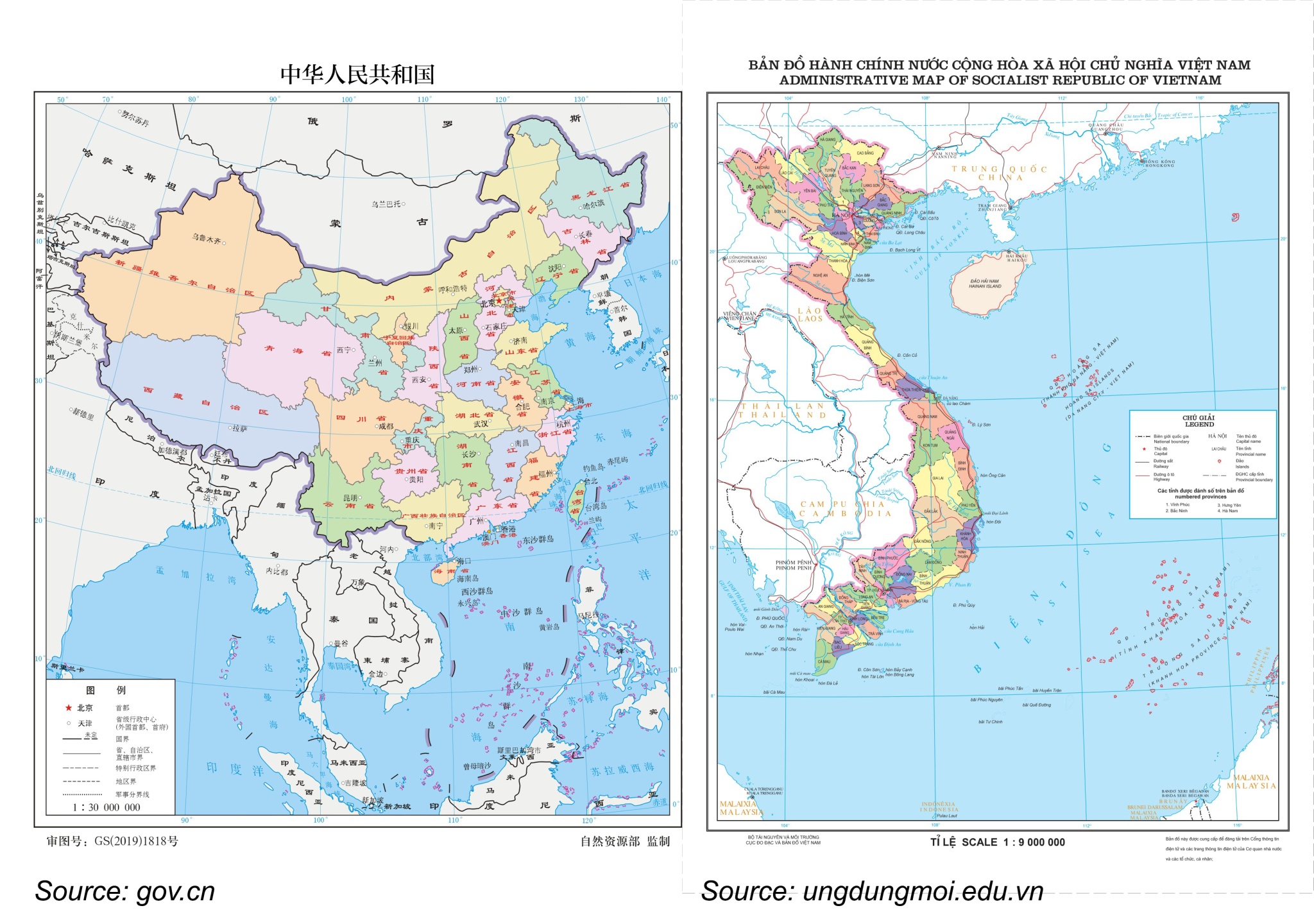

While China is Vietnam’s largest trade partner, the two countries are engulfed in a bitter dispute over the South China Sea, which, according to many analysts, could become the theatre of a large-scale military confrontation in the coming decades. Without going into detail about the conflict’s timeline or the parties’ arguments, it is important to stress that it acquired a new quality in the early 2010s when China embraced a more assertive foreign policy. The People’s Republic of China had taken over the Kuomintang’s territorial claims within the so-called eleven-dash (later nine-dash) line, something other South China Sea states vehemently oppose. As the two countries’ official maps below demonstrate, China and Vietnam both claim the Paracels and the Spratlys in their entirety (since recently, the Chinese 9-dash line has, in fact, ten dashes).

The reality on the ground (or, put more properly, “on the water”) is such that the Spratlys consist of hundreds of islets, reefs and shoals, known collectively as maritime features. Vietnam and China de facto control about a dozen such features each, having deployed their military garrisons there. The remainder is partially controlled by the military of the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. The Paracels are controlled by China, which forced out a South Vietnamese garrison in 1974. China also gained control over some of the Spratlys as a result of force operations against Vietnam and the Philippines.

The reality on the ground (or, put more properly, “on the water”) is such that the Spratlys consist of hundreds of islets, reefs and shoals, known collectively as maritime features. Vietnam and China de facto control about a dozen such features each, having deployed their military garrisons there. The remainder is partially controlled by the military of the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. The Paracels are controlled by China, which forced out a South Vietnamese garrison in 1974. China also gained control over some of the Spratlys as a result of military operations against Vietnam and the Philippines.

According to Russian researches Andrey Dikaryov and Alexander Lukin, China’s interest in this area has four components:

- a subjective feeling of historical rights on almost the entire South China sea combined with the ambition to promote the country’s prestige;

- a need for “strategic depth” to facilitate the naval defence of coastal cities;

- an ambition to have strategic access to the Indian and Pacific oceans to implement the Belt and Road Initiative;

- a desire to have unhindered access to sea resources, especially fish and hydrocarbons.

All of this runs against America’s vision of the balance of powers and its own role in Asia. Obama’s pivot to Asia resulted in a policy of containing China, veiled at first, and increasingly open later on. Washington began to reinforce its old alliances in the region, first of all, with the Philippines, and intensified its political dialogue with Vietnam, which had been launched in the mid-1990s. The United States’ position on the South China Sea dispute has evolved from neutrality and a refusal to take a position on the legal merits of the competing claims to sovereignty to open support of those countries which oppose China.

In 2020, the United States for the first time officially rejected Beijing’s claims within the nine-dash line and supported the Philippines’ position, invoking the 2016 decision of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. According to RAND Corporation’s Derek Grossman, following this announcement, “Vietnam probably felt just a little more confident that the US planned to support Hanoi in defending Spratly Island claims within its EEZ.” Remarkably, unofficial American support for these claims has existed for quite a long time: back in 2014, Raul Pedrozo, a renowned maritime law specialist, wrote that “it would appear that Vietnam clearly has a superior claim to the South China Sea islands.”

It should be noted that at the peak of globalization, mutual territorial claims in fact did not hinder economic and political relations between the regional powers. Thus, China, despite the bitterness of the territorial dispute, was the first nation to sign a comprehensive strategic partnership with Vietnam in 2008. Vietnam’s relations with Russia were upgraded to this status four years later (though since 2001 it had been the country’s only strategic partner). Vietnam claims the same features in the Spratly archipelago that the Philippines, but this does not prevent the two countries from coordinating their positions in the dispute with China. Finally, Taipei formally claims all features within the nine-dash line and has, consequently, a territorial dispute with both Vietnam and the Philippines, but is in fact on their side. The “strategic ambiguity” that underlies Washington’s Taiwan policy is practiced to varying degrees by all claimants in the South China Sea dispute.

However, more active involvement of the United States in the dispute will require its participants to shift to more unambiguity and, probably, taking more confrontational stances. That would be a serious challenge for Vietnam, whose defence policy is based on the “four no’s” principle:

- no military alliances;

- no siding with one country against another;

- no foreign military bases or use of Vietnamese territory to oppose other countries;

- no using force or threatening to use force in international relations.

It is obvious that America’s support for Vietnam is consistent with the overarching goal of containing China. In addition, whereas in realpolitik terms the US-Vietnam comprehensive strategic partnership looks natural, there is a clear divergence between the two countries with regard to values. Well-versed as the United States is in manipulating values and national interest arguments, it is quite difficult to imagine a really close alliance between Washington and a formally socialist country. Especially as many American Vietnamese, who are the most Republican-leaning Asian-Americans, are sceptical about enhancing ties with a “communist regime,” which, according to some analysts, is “closer to the Chinese side of the Sino-US spectrum.”

Both sides realize that the US-Vietnam comprehensive strategic partnership has limits. Vietnam is not the only country aspiring to take over the role that was considered China’s destiny at the dawn of globalization (even though in today’s conditions, a replay of the Chinese success story is impossible). At the same time, Washington’s policy of containing China gives Vietnam an opportunity of historic proportions. As noted in the beginning, the country began to enjoy the benefits of globalization a dozen years after China. Today, as globalization as we once knew it unravels, some states receive privileges “just for being there,” and Vietnam’s leadership cannot afford to miss the development opportunities opening up for the nation of 100 million. Risks are high as well, and the end result depends on the skill of the helmsmen navigating between the great powers’ conflicting interests.