As the continent continues to grow, according to the underlying logic of the scramble for Africa, great powers either need to assert their influence or risk falling behind. Considering the heightened interest, Africa can use the summits as a platform to lobby support for its own development programmes and projects such as Agenda 2063, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and other AU flagship projects, which are all important cornerstones of Africa’s sovereignty, writes Lora Chkoniya, Research Fellow at Center for Middle East and African Studies, Institute for International Studies, MGIMO.

Against a backdrop of heightened geopolitical competition in Africa, the great powers are designing increasingly elaborate cooperation formats, using summits as their institutionalised framework of choice to build long-term relations and secure influence, resources and opportunities on the continent. However, unlike the 19th Century “Scramble for Africa”, which was marked by exploitation, abuse and inequality, Africa today has a consolidated voice, abundant choice and greater freedom to build relations with external actors in a way that enhances its growth potential as a rising political and economic powerhouse.

Within this context, Africa’s biggest partners are taking their own approaches to hosting large-scale joint events with the continent, seeking creative ways to outdo their “competition” and secure their own niche in Africa’s future. Some are actively spearheading new formats, as in the case of Russia, which hosted the first ever Russia-Africa Summit in 2019. Others are resuscitating old ones, as the United States did in 2022 during the second US-Africa Leaders Summit, which took place after an 8-year-long hiatus following the first such event in 2014. Some are continuing long-term efforts, such as China in the case of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, which was launched 23 years ago, at a time when Africa was infamously written off as a “hopeless continent”by The Economist and faced limited partnership opportunities. The same goes for Europe in the case of the Africa-EU Partnership, which was formally established in 2000 at the first Africa-EU Summit in Cairo.

Despite an abundance of opportunities for cooperation and no need for a zero-sum game, a picture of how influence is being distributed is slowly beginning to take form.

Beijing for example, is emerging as the supreme financial powerhouse in Africa, and has been its number one trade partner since 2009. Moscow has secured its niche as exporter of security to the continent against the backdrop of growing Islamic radicalism and instability. The EU and US maintain their leverage thanks to their wide mandate in key international financial institutions that provide loans, grants and technical assistance that are instrumental in crisis management and facilitating economic growth; however, this support comes with political strings attached. Many African governments are not willing to risk losing this support.

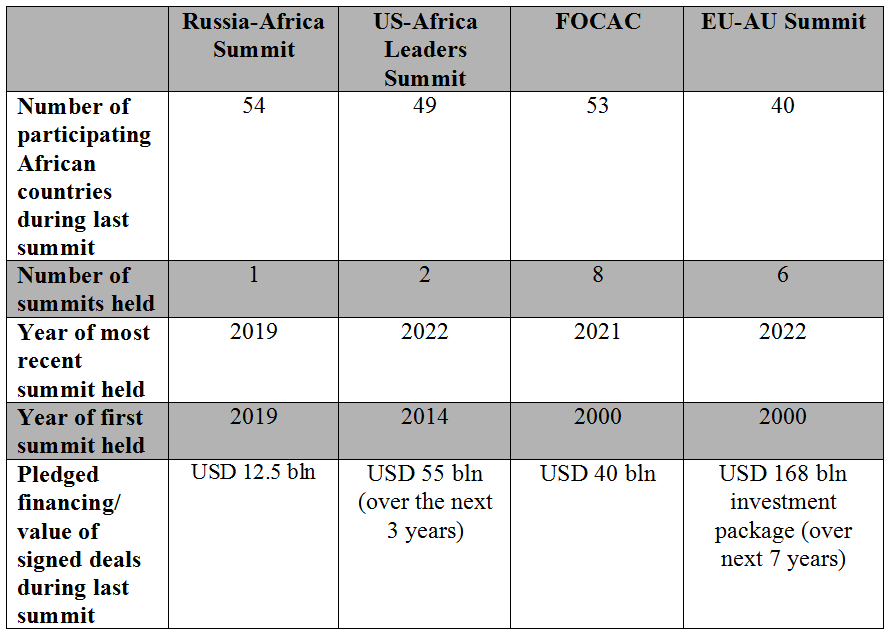

Table 1. Comparison of Key Characteristics and Takeaways From 4 Key Africa Cooperation Summits

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)

Established in 2000 as a means of enhancing partnership between China and all but one African countries (the exception being Eswatini, Taiwan’s last African ally and the beneficiary of significant Taiwanese investment and donation), FOCAC is potentially the most elaborate, long-term and far-reaching institutionalized partnership format of any maintained by the great powers with the continent. The most recent, eighth FOCAC was held in Senegal in 2021 and was focused on the adoption of 4 key resolutions: the Dakar Action Plan (2022-2024), the China-Africa Cooperation Vision 2035, the Sino-African Declaration on Climate Change, and the Declaration of the Eighth Ministerial Conference of FOCAC.

During the event, China committed USD 40 bln worth of financing, falling USD 20 bln short of the previous commitment in 2018. Although some might view this as a shift of priorities, it is just a drop in the ocean of China’s overall financing to the continent. In addition, USD 1 bln worth of vaccines were pledged during the event.

Beijing has proved its credibility as a long-standing partner of modern Africa, and the Chinese summit approach is unique in that it provides a comprehensive economic-political-security-soft power nexus for all Chinese activities in Africa. This means that the FOCAC is ultimately an umbrella structure to all 53 China-Africa state bilateral relationships, which provides for more structured, cohesive and effective cooperation with the continent.

The US–Africa Leaders Summit

Initially launched in 2014 yet later forgotten under the “America first” policy of President Trump, the US–Africa Leaders Summit returned in 2022 and was mainly aimed at resetting somewhat disregarded relations with the continent. A total of USD 55 bln in of financial commitments was pledged, with particular focus on the key priority areas of the AU’s Agenda 2063.

Notable is what seems like the calculated decision to avoid focusing on the usually expected trio of democracy, human rights, and governance in the summit agenda, instead giving priority to infrastructure projects and technological development, as well as issues related to food security. This might be explained by African leaders’ pushback against patronizing attempts to interfere in local political affairs under the umbrella of democracy. In addition, there was no mention of Chinese and Russian influence in Africa, which comprised a significant point in the US administration’s new Africa Strategy, released just earlier that year.

EU-AU Summit

In March 2022, 40 African leaders gathered in Brussels for the EU-AU Summit. A 168 USD bln investment package was presented with particular focus on energy, transport, digital infrastructure, health and education. This amount is significant within the context of the EU’s total FDI volume in Africa, approximately USD 250 bln as of 2021. For context, the largest holders of foreign assets in Africa today are European, led by the UK (USD 65 bln) and France (USD 60 bln). Another unique feature of the summit was the decision to release USD 100 bln worth of SDRs made available to African countries, some of which are grappling liquidity issues.

The format also foresees a “follow-up monitoring mechanism” designed to track commitments by holding periodic meetings between the AU and EU to review progress in implementing commitments. Considering the preconception that high-level summits rarely lead to actionable recommendations and real projects, the mechanism is a best practice to take note of. The FOCAC also provides such a follow-up mechanism.

Conclusion

As the continent continues to grow, according to the underlying logic of the scramble for Africa, great powers either need to assert their influence or risk falling behind. Considering the heightened interest, Africa can use the summits as a platform to lobby support for its own development programmes and projects such as Agenda 2063, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and other AU flagship projects, which are all important cornerstones of Africa’s sovereignty. The value of supporting ongoing African-led projects in the spirit of “African solutions to African problems” is likely to be well-received.

In addition, patronizing comments and offering the charity-case treatment are clearly a losing strategy for working with the Africa of 2023. The global powers understand this and are taking responsibility for historical wrongs, as seen, for example, by President Biden kicking off the US summit with an apology for his “nation’s original sin” and the “unimaginable cruelty of slavery.” Others have less to apologize for and instead focus on the positives and Africa’s growing role in the world of tomorrow. For example, President Putin opened the 2023 Russia-Africa Parliamentary Conference with the words, “We are convinced that Africa will become one of the leaders in the emerging new multipolar world order,” and Chinese leader Xi Jinping opened the 8th FOCAC saying that “China and Africa have embarked on a distinctive path of win-win cooperation.”

While each party will have their distinctive view of what that win-win cooperation should look like, the winning recipe will likely enhance Africa’s sovereignty by financing capacity building programs, closing the infrastructure gap, and finding sustainable solutions to provide food and energy security, amongst others. Summits provide a framework within which these tasks can gain structure, accountability can be boosted and the overall positive effect for Africa enhanced.