During the first global financial crisis since 2008, sovereign wealth funds were not only at the front of the fiscal response but also actively investing in their countries’ economies. For governments with a stabilisation or a savings fund with liquidity, the immediate action was to draw down on the fund or to access international debt markets. The main difference to the Global Financial Crisis is that sovereign funds have mainly invested domestically across all sectors, as opposed to overseas investments in financial services in 2008-9, writes Enrico Soddu, Head of Data & Analytics, International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds.

Valdai Club Programme Director, Yaroslav Lissovolik, recently debated on these pages that the international multilateral system struggled to react to the pandemic. This article will argue that some state actors, such as sovereign wealth funds, managed these difficult conditions well. As special-purpose investment funds owned by the general government for macroeconomic purposes, sovereign wealth funds hold, manage, or administer assets to achieve financial objectives.

In 2008, sovereign wealth funds made headlines during the global financial crisis, supporting banks in developed markets when capital flows froze and central banks were slow in pulling monetary levers to help financial institutions. At the same time, with support from the US Treasury Department, the IMF and the OECD, 26 sovereign wealth funds agreed on a governance framework known as the Santiago Principles, the proponents of which established the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF), a permanent global organisation to represent the interests of sovereign wealth funds and encourage robust governance practices.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the world economy shuddered almost to a halt, and monetary policy alone was not the answer. Governments had to resort to expansive fiscal policies, to a degree not seen since the end of the Second World War. Those countries with a sovereign wealth fund had enough fiscal capacity to increase spending, respond to emergencies and lowering taxes when necessary to stimulate their economies.

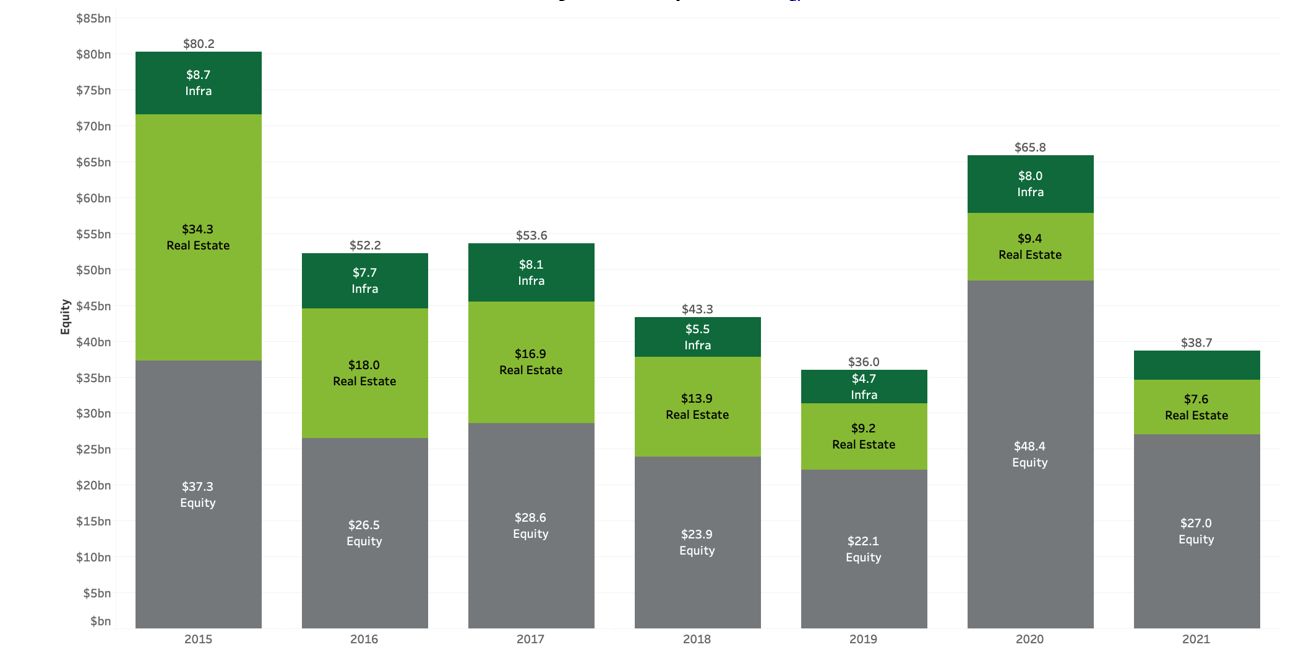

The IFSWF’s database of sovereign wealth funds’ publicly disclosed direct investments, suggests that they entered the COVID-19 crisis in defensive mode. According to IFSWF data, at the end of 2019, sovereign wealth funds had committed the lowest amount of capital into direct investments since 2015: only $35.9 billion,17% less than in 2018. Additionally, research from State Street and IFSWF, demonstrated that many sovereign wealth funds and other institutional investors were already either overweight cash or underweight equities before March 2020.

Sovereign wealth funds thus entered the pandemic with high levels of liquidity enabling them to support local economies or investing counter-cyclically in international markets in March 2020. It is no surprise that sovereign wealth funds’ direct investments reached a five-year high in 2020 to $65.9 billion, almost doubling from $35.9 billion in 2019. This high investment level has continued into 2021. As of August, their direct investments reached a total of $39 billion, already higher than the whole year of 2019.

Chart 1.1 SWF Direct Investments by Value ($Billion)

Source: IFSWF Database, as of 3 August 2021.

During the pandemic, there were four main approaches taken by countries with sovereign wealth funds:

-

Governments tapping their stabilisation and saving funds for spending purposes.

-

Strategic funds directly involved in the pandemic relief efforts.

-

Strategic funds pursuing the domestic agenda, regardless of COVID-19.

-

Hybrid strategic and saving funds’ opportunistic investments in international markets.

Saving and Stabilisation Funds to the Rescue

The pandemic had macroeconomic, social, and fiscal impacts on sovereign wealth funds. The world’s largest sovereign fund, Norway’s $1.1 trillion Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), made its largest ever contribution to the government. In October 2020, Norway’s Ministry of Finance announced that it would be withdrawing almost 3% from GPFG: $37 billion to cushion the country's rising spending due to the pandemic.

Those countries with a stabilisation fund, more often than not,dipped into it to stabilise their currency and support the economy when needed. For example, the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ) distributed $8.7 billion to the government to help finance the COVID-19 response.

Chile also took advantage of its savings and stabilisation resources to support the government's financing needs. In 2020, Chile’s Ministry of Finance withdrew a total of $5.66 billion from its two funds: the Economic and Social Stabilization Fund (ESSF) and the Pension Reserve Fund (PRF), and during April 2021, another $3.232 billion. Of these, $ 1.5 billion was withdrawn from the Pension Reserve Fund (PRF) and $ 1.8 billion from the Economic and Social Stabilization Fund (ESSF).

However, if sovereign wealth funds do not have clear withdrawal rules, governments can draw on their stabilisation funds too frequently and deeply, creating friction between the Ministry of Finance and the funds. For example, Botswana’s government made frequent withdrawals from the Pula Fund during the pandemic to support the economy. The Pula Fund fell from P52.7 billion ($4.46 billion) in June 2020 to P46.2 billion ($4.16 billion) in March 2021, according to Bank of Botswana’s figures. Consequently the Bank of Botswana is seeking legislation to limit access to its sovereign wealth fund.

Direct Response to the Pandemic

Most sovereign wealth funds established for strategic and development goals have been directly involved in their government’s policy response during the pandemic.

One of the most notable examples was the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), which spearheaded its country’s effort in fighting the virus. RDIF dedicated its resources to developing a coronavirus vaccine virtually overnight, according to its CEO Kirill Dmitriev in an interview with the Wall Street Journal. It established several international partnerships in projects to detect pneumonia, in coronavirus diagnostics systems, and in antiviral drugs – initially used to fight the worst symptoms of COVID. Most notably, the fund spent approximately $200 million to develop the world's first coronavirus vaccine – Sputnik V – developed with the Gamaleya National Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology. RDIF maintains a license to sell it abroad, where it is approved in 67 countries.

RDIF wasn’t the only sovereign fund financing vaccine development. Singapore’s Temasek Holdings investee company, BioNTech, pivoted early to develop a vaccine with Pfizer. The jab has 95% efficacy against symptomatic illness and almost universal effectiveness in preventing serious illness. Another Temasek portfolio company, Clover Biopharmaceuticals, has also leveraged its proprietary technology for vaccine solutions in various stages of trials.

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority’s 2018 investment in Moderna paid off when the FDA approval to produce COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020, turbocharged the company’s share price. As of August 2021, its stock is up by 395% year-on-year.

In May 2020, the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF), took a more traditional role, allocating €2 billion ($2.4 billion) to the Pandemic Stabilisation and Recovery Fund (PSRF) as part of the government’s relief measures to the Covid pandemic. The PSRF supports companies with more than 250 employees or with an annual turnover above €50 million, with the flexibility to consider smaller companies if they are of significant national or regional economic importance. Between May 2020 and the end of the year, ISIF allocated a total of 90% of all its direct and indirect investments to pandemic-impacted businesses. For example, it invested in the national carrier Aer Lingus and tourist accommodation provider, Staycity. As of 2021, ISIF has a pipeline of over €600 million ($720 million) in potential investments from the PSRF.

Temasek was another sovereign fund directly involved in supporting local companies. For example, the state holding company supported several initiatives in Singapore, from the development of new test kits, to the expansion of lab capabilities. In containment and contact tracing, Temasek set up community care facilities (CCF), at Singapore Expo, the first CCF had an operating capacity of 8,000 beds, to care for the younger COVID-19 patients. This anticipatory move helped to contain the community spread. Temasek continued to support its most vulnerable portfolio companies during the pandemic, participating in a $2 billion rights issue by Singapore Airlines and in 2021 it committed to participate in the rights issues of commodities trader Olam and offshore marine company Sembcorp Marine.

Strategic Funds Doubling Down on their Mandate

According to IFSWF data, there are currently only ten pure stabilisation funds and 26 saving funds globally. Therefore, only a few countries had the resources to dip into a rainy-day fund to cushion their budget needs. However, some recently established strategic funds continued to push forward with their long-term domestic agenda, not distracted by the pandemic.

In 2020, the Turkey Wealth Fund (TWF) invested a total of $5.8 billion to consolidate the local insurance and banking sector, and take a 26.2% stake in mobile phone operator Turkcell. TWF managed to attract foreign investment as well, selling 10% of Istanbul’s stock exchange Borsa İstanbul to the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) for $200 million.

The Sovereign Fund of Egypt, established in 2018, and only recently funded with the objective of attracting private investments in Egypt’s underused assets, has already closed two deals in 2021, investing in the Arab Investment Bank and to establish the Lighthouse Education platform, attracting several local and regional partners.

Some other domestic investment funds were involved in large transactions borne out before the pandemic. For example, Italy’s CDP Equity led an investor group that acquired Atlantia’s stake in Italian motorway network Autostrade per l’Italia for approximately €8.1 billion ($9.7 billion). The infrastructure group Atlantia had put its 88% stake as a consequence of pressure from the Italian governments after the August 2018 collapse of the Morandi bridge in Genoa, which killed 43 people.

Hybrid Funds’ Opportunistic Approach

Two notable exceptions to the more direct approaches during the pandemic are offered by hybrid funds with both a domestic and an international investment mandate: Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company. Mubadala took advantage of the market volatility by triggering a series of tactical trades and public equity investments, according to its 2020 annual review. The fund had one of the most active investment years in its history according to David Crofts, executive director Enterprise Risk at Mubadala, in an interview for IFSWF’s 2020 annual review.

In addition to supporting the Saudi economy, PIF invested more than $10 billion in US and European blue-chip companies when the stock market crashed in March, in the sectors most hit by the pandemic such as leisure, travelling and energy companies. PIF disclosed a total of over $2 billion in stakes of four oil and gas companies – BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Suncor Energy and Total. The Saudi fund also invested $1 billion in travel and leisure companies Marriott International and cruise company Carnival. Its purchases in public markets made sovereign wealth fund direct investments in the public market jump five times from $6 billion in 2019 to $28 billion in 2020.

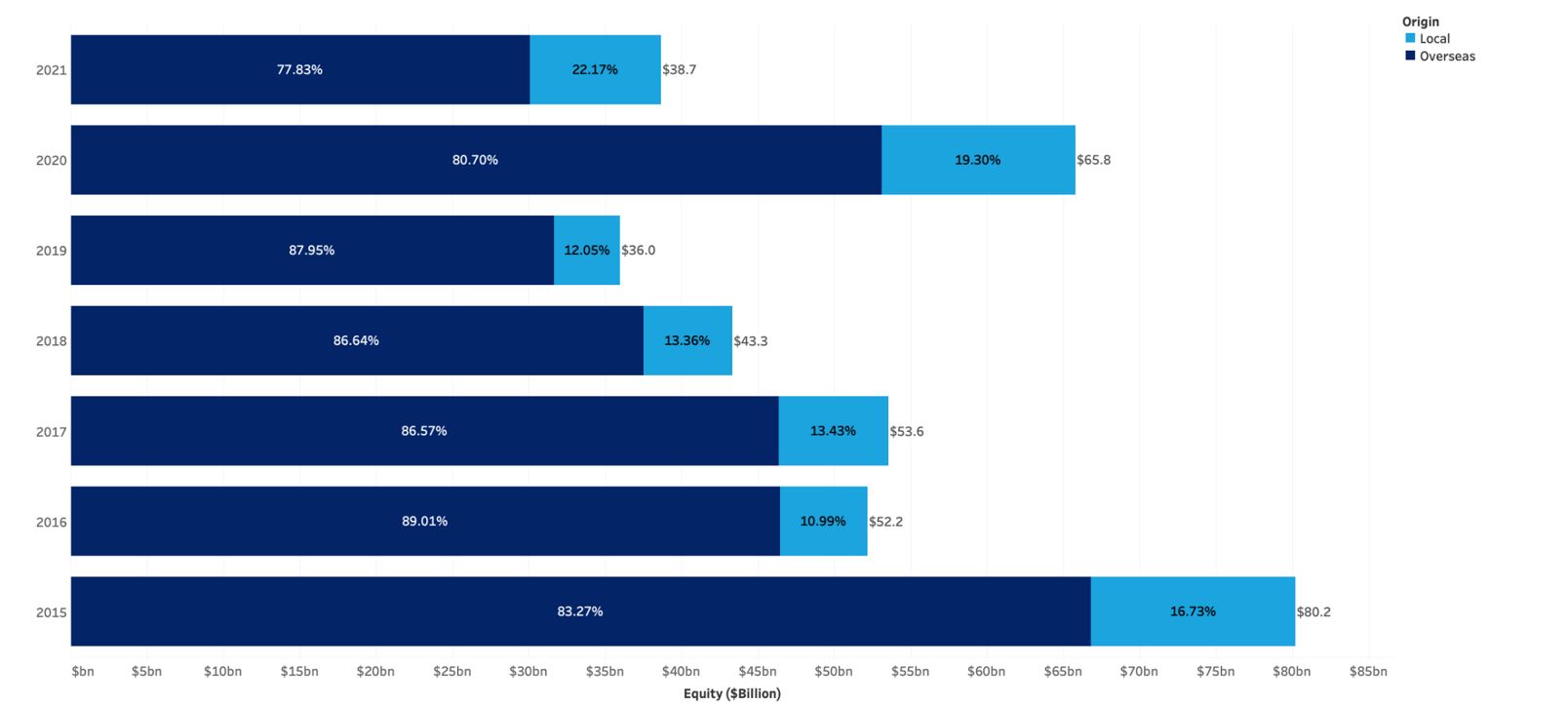

During the first global financial crisis since 2008, sovereign wealth funds were not only at the front of the fiscal response but also actively investing in their countries’ economies. For governments with a stabilisation or a savings fund with liquidity, the immediate action was to draw down on the fund or to access international debt markets. The main difference to the Global Financial Crisis is that sovereign funds have mainly invested domestically across all sectors, as opposed to overseas investments in financial services in 2008-9.

Chart 1.2 SWF Direct Investments by Value ($Billion) in domestic and international markets

Source: IFSWF Database, as of 3 August 2021.

Some new strategic funds accelerated their activities, even in the middle of the pandemic, as TWF’s effort to consolidate the insurance and savings sector in Turkey has shown.

On the other hand, some funds with a hybrid mandate doubled down both on the domestic front as well as taking advantage of low valuations in international stock markets at the peak of the crisis in March 2020, like Saudi’s PIF and Mubadala have shown.

In short, sovereign wealth funds not only guided the fiscal response in their economies, but have financed healthcare companies fundamental in bringing several vaccines to market.

The author would like to thank Dr Victoria Barbary and Duncan Bonfield for valuable comments and suggestions.