Introduction

The year 2022 witnessed intensified dialogues between top Syrian and Turkish officials. These kicked off with an August meeting in Damascus between Ali Mamlouk, the Head of the National Security Bureau of the Ba’ath Party and a Special Security Advisor to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and Hakan Fidan, the Head of Turkiye’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT). They concluded with a tripartite December meeting in Moscow, where Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu hosted his Syrian and Turkish colleagues Ali Mahmoud Abbas and Hulusi Akar (remarkably, Ali Mamlouk and Hakan Fidan were also present). Those meetings prompted world media and political experts to speculate about an “unthinkable” Syrian-Turkish rapprochement becoming “thinkable”. The expectations were raised in January 2023 when Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu acknowledged the possibility of meeting his Syrian counterpart Faisal Mekdad early in February, although the series of deadly earthquakes, which struck both Turkiye and Syria, led to the postponement of this event.

Despite the shared feelings of loss among regular Syrians and Turks in the wake of the February earthquakes along the Turkish-Syrian border, as well as Russian mediation efforts that had resulted in bringing Syrian and Turkish negotiators closer together, prospects for a foreseeable rapprochement between Damascus and Ankara remain questionable. In the era of globalization, where sovereign states have become much more interdependent at the global, regional, and sub-regional levels, international conflicts have been influencing each other to a significantly greater extent. A plain example is the current Ukrainian crisis, which has been deeply affecting the Syrian and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflicts. Under such vulnerable circumstances, Russian-Turkish relations have become highly dependent on diplomatic “battles” between Ankara and Moscow over retaining vs. enhancing influence in different regions, namely, in Syria and the South Caucasus.

Syrian Conflict vs. Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh

It doesn’t take much of an effort to understand that the South Caucasus largely resembles Syria in terms of its deep political fragmentation and sometimes opposite orientation of states of the region and local political forces toward foreign actors. Those realities imply that the Syrian and Nagorno-Karabakh conflicts are highly internalized.

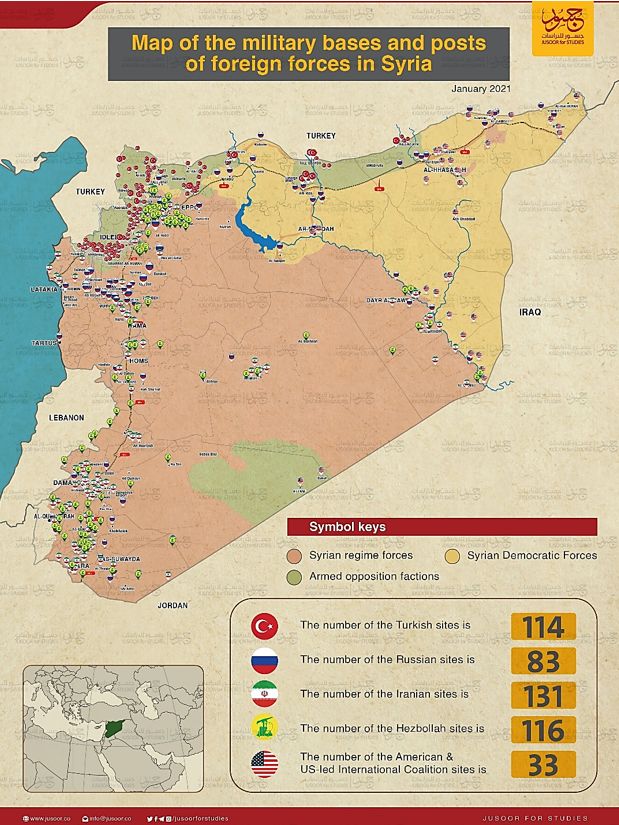

The shortlist of major stakeholders of the Syrian conflict includes Iran, Russia, Turkiye, the US (and its Kurdish allies), and the Iran-affiliated Lebanese Resistance Movement Hezbollah. All of them have a visible political and military presence across Syria, as illustrated by the following map:

Source: Map of the military bases and posts of foreign forces in Syria//Jusoor Center for Studies, January 12, 2021.

Other stakeholders of the Syrian conflict include China and the Gulf Cooperation Council Arab countries, which enjoy limited economic influence in Syria but lack their own zones of territorial control.

A similar mosaic of presence and influence may be found in the South Caucasus. Thus, it is noteworthy that Georgia is committed to partnering with Euro-Atlantic and European institutions, while Armenia is part of the Russian-led CSTO military alliance. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan and Turkey are military allies. Turkey’s decision to side with one of the conflicting parties in Ukraine will push Azerbaijan to take a similar approach. Geopolitical and geo-economic fault lines in the South Caucasus may create challenges that will influence the trade and economic relationship between the Caucasian countries and their neighbours. The recent developments showed that for Moscow, the Russian troops in Nagorno-Karabakh are sufficient (but constantly being challenged) to secure Russia’s interests in Baku in the long run and contain Turkey’s interests in the region. This has especially been the case since the Shushi Declaration on June 2021 that was signed between Baku and Ankara aimed to strengthen the military, security and diplomatic ties between the two Turkic countries. That made some experts speak about Turkey breaching Russia’s sphere of interest.

By signing the Shushi Declaration, Azerbaijan solidified its military and security relations with NATO member Turkey. As Ahmad Alili from the Baku-based Caucasus Policy Analysis Center argued, Azerbaijani has become a “major non-NATO ally” for Turkey, as Israel, Egypt, and Japan are for Washington. In this case, Turkey offered the same position to Azerbaijan. The Shushi Declaration is a document signalling the new international and security status quo of the South Caucasus. “With Georgia having publicly declared NATO and EU aspirations, and Azerbaijan having closer military and diplomatic links with NATO member Turkey, the region lost its “Russian backyard” status and becomes a “Russian-Turkish” playground”, added Alili. This factor has pushed Moscow to increase its soft pressure over Baku and sign an “allied declaration” on February 2022 aiming to solidify its political presence in the region.

Russian-Turkish Cooperative Rivalry in the South Caucasus: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Road to the November 10, 2020 Trilateral Statement

While both countries “understand” each other with regards to Syria, Turkey’s aspiration to play a greater role in the South Caucasus has put this relationship to the test. With the outbreak of the second Nagorno-Karabakh war (September 27 - November 9, 2020), Turkey saw a historical opportunity to exert its influence in its immediate neighbourhood – the South Caucasus. Unlike Syria, this region has been a centuries-old sphere of national interest for Russia; since 1828. To challenge Russia, Turkey threw its full active military and diplomatic support behind Azerbaijan in its war against the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

During the war, both Moscow and Ankara played tit-for-tat against each other. Many observers noticed that while Russia was rather defensive in its “backyard,” in the South Caucasus, it was seemingly offensive in Syria, with the Russian air force bombing Turkish and Turkish-backed rebel positions in Idlib. By putting pressure on Ankara through Syria, Moscow was trying to balance its vulnerabilities with Turkey. Turkey too had another plan in the South Caucasus: to exert pressure on Russia. Meanwhile, in November 2020, the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) was inaugurated and connected to the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), which allowed for Caspian gas to be delivered to Southern Europe through Turkiye, bypassing Russia. This project is crucial for Turkiye, as it transforms the country from an importer to a transit route for gas. The geopolitical nature of this project was to decrease Europe’s gas dependency on Moscow.

On a diplomatic level, Turkey tried to launch “Astana style” diplomatic measures to address Nagorno-Karabakh. However, given the fact that the conflict was taking place in the post-Soviet space, Russia failed to see much incentive in engaging in a bilateral track with Turkey in the form of a new “Astana style” process where Turkey and Russia were going to be equal partners, addressing a conflict in Russia’s “backyard”. Such a scenario would have legitimized Turkey’s intervention and presence in the region. For this reason, Maxim Suchkov, a Moscow-based expert at the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), explains that Russia didn’t want to directly intervene in the course of the war, taking a “watch and see approach.” Suchkov argued that if Azerbaijan continued its military operations and occupied Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkiye’s gambit would have paid off as Baku would be forever grateful for Ankara, and Turkiye’s influence in the region would grow. However, this would have caused an ethnic cleansing and Yerevan would blame Moscow. By losing its only military ally in the region, Russia would have lost the whole region. Hence, Moscow tried its best to satisfy Baku, but also took steps to not completely alienate Yerevan, which had been crushed in Azerbaijan’s autumn 2020 blitzkrieg.

Interestingly, the Russian-broken November 10, 2020, trilateral statement which ended the war was not in favour of Turkey. Ankara was pushing for a complete Azerbaijani victory or at least asking for the deployment of Turkish peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh alongside the Russian forces. Both scenarios failed even though Turkiye had become an active player in shaping the new geopolitical landscape of the region. Hence, even though Russia has shown dissatisfaction with Turkish intervention in its traditional sphere of influence and drawn “red lines,” Moscow eventually recognized Turkiye as a junior player in the region, while still not tending to share parity in the post-conflict regional order.

Post-2020 Regional Order in the South Caucasus

However, the military conflict in Ukraine has shaken the balance of power in the South Caucasus. Facing increasingly hostile West-Russia relations, the region keeps turning into a new confrontation zone, while Azerbaijan and Armenia continue to navigate to secure their vital interests. Thus, it is very important which side Turkiye takes in this battle.

As Yerevan is aiming to secure the physical safety of the local Armenian population in Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan has been pushing to resolve the Karabakh issue by force, which would significantly reduce Moscow’s presence in the region, especially taking into account the 2025 expiration of the Russian peacekeepers’ mandate.

The 2020 trilateral statement, it seems, is not bringing long-lasting peace to the region. Both Yerevan and Baku continue to interpret the ninth article of the November 10 trilateral statement differently. While Azerbaijan argues that Armenia should be providing a “corridor” to connect the Azerbaijani mainland to the Nakhichevan exclave through Syunik (southern Armenia), which Baku calls the “Zangezour corridor,” Armenia refutes this, insisting that the clause mentions the restoration of transit channels (highways, railways…), with both sides using the roads. Moreover, Baku adds that if Yerevan doesn’t provide any corridor in Syunik, Azerbaijan will also block the Lachin corridor amid Yerevan's insistence that the status of the Lachin corridor should not be linked to the opening of transit channels. This has pushed Iran to make a “comeback” to the region, warning that any territorial change of the Armenian-Iranian border is a red line for Tehran. Tehran believes that such changes could threaten its geopolitical interests, including a Moscow-Tehran-New Delhi-backed North-South transport corridor.

Despite all the odds, and the continuation of the blockade of the Lachin corridor, the only land route connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, the Russian troops are the sole guarantors of the security of Karabakh Armenians. Unlike what many analysts thought, the defeat of Armenia in the 2020 war did not decrease Russian influence in Armenia; on the contrary, Russia enjoys more influence, despite Yerevan’s growing reluctance towards Moscow due to the latter’s inability to prevent Baku from attacking Armenia’s sovereign territory or prevent the blockade of the Lachin Corridor. On the other hand, Baku officials are not hiding their true intentions; in that they are not in favour of renewing the mandate of the Russian peacekeepers in 2025 and are insisting on the “reintegration” of the region into Azerbaijan. If Baku fulfils its objective and engages in demographic engineering around the region, and forces Armenians to leave Nagorno-Karabakh, then there will be no more justification for the Russian presence in the region and Moscow will lose its leverage over the entire region.

Source: The map presented by Armenia at the ICJ. Armenia releases map of territories ‘seized by Azerbaijan’ since 2020, OC Media, February 1, 2023.

Future of the “Co-opetition”: Can the Nagorno-Karabakh Scenario Play Out Again in North-Eastern Syria?

The experience in Nagorno-Karabakh has shown that despite Turkey’s policy of containing Russia’s presence in the region, Moscow has successfully (for now) preserved its influence there. However, the outcome of the crisis in Ukraine is still not clear, and the concerned parties in the region have already felt its impact. In the long run, Azerbaijan and Armenia will have to make a strategic decision to which pole they belong. A future balancing act may not serve the vital interests of both parties. Suppose that the West succeeds in persuading Turkey to make certain political concessions regarding Russia, with the Turkish elites facing mounting domestic pressure over the disastrous consequences of the recent earthquakes, amid the uncertainty around upcoming Presidential and parliamentary elections. In that case, Ankara’s geopolitical choices will have a significant impact on Baku. Will Ankara and Baku find themselves in opposite camps?

Moreover, a pending possible withdrawal of US troops from North-Eastern Syria amid the unclear political future of the Syrian Kurds and their parallel economy is fraught with the risk of creating a sub-regional vacuum of power. It could eventually push Turkey and Russia to manage their cooperative rivalry, courting both Damascus and the self-proclaimed “Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria” (AANES), run by Kurdish military and political forces.

Yet, patterns of modus vivendi and even modus operandi are unclear. As many Kurds fear a possible US withdrawal, Turkey may launch new trans-border military interventions in Syria (like the most recent anti-terror “Operation Claw-Sword” conducted in November 2022 against Kurdish YPG militants). Those operations may coincide with mounting pressure on the Kurdish leadership in Syria. In this case, the presence of Russia as the arbitrator, even on a modus operandi basis, would satisfy Ankara, Damascus, and the AANES leadership. Therefore, it could accelerate the speed of the Syrian-Turkish rapprochement process cementing, although – as usual – tactically, Russian-Turkish “co-opetition”.