Outside the core of the capitalist bloc of the world system, the emerging powers continued to move in a contrary direction with the formation of new economic and political regional associations. The Eurasian Union, the Shanghai Cooperation Agreement and the Chinese-led One Belt One Road initiative all gathered momentum. A new configuration of regional states is taking shape. Ironically perhaps, unlike developments in the core capitalist states, these states still subscribe to the general principles of free global markets and economic liberalism. The new regional associations seek to widen markets rather than to bring them under state control.

The Growing Power of China

The Nineteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2017 must be considered a major watershed. Unlike in the European post-socialist countries, where the anniversary of the October Revolution was met with a resounding silence, in China under the Communist Party leadership of President Xi Jinping, socialism was endorsed. In his opening speech, ‘socialism’ was mentioned no less than 70 times. ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’, summarised under fourteen points, promises to be the philosophy governing Chinese policy. It heralds a more assertive nationalistic role for China in international affairs.

It has three major components: socialism, Chinese characteristics and ‘a New Era’.

Deng Xiaoping had earlier coined the notion of socialism with Chinese characteristics. In this formulation, socialism retained an economic plan under the hegemony of the Communist Party, while the Chinese characteristics signalled the introduction of the market and competition. Xi Jinping’s definition of a ‘new era’ heralds movement to a new phase of economic and political development, albeit along the path trod by Deng Xiaoping. Policy represents a more interventionalist, even assertive, role for China in world affairs. There is a call to strengthen and upgrade China’s military power and to move into a technological level of economic development.

The ‘New Era’ might also be interpreted as a more coherent and consensual form of Chinese economic nationalism predicated on the idea of the Chinese nation being a single community. This conception of identity will help to counter secessionist movements should they arise. The Eurasian project, and the Silk Road and the Maritime Road initiatives put China at the centre of an expanding regional centre of political and economic power. This is what Xi Jinping considers to be part of a ‘national rejuvenation’.

Economic and Social Challenges to ‘National Rejuvenation’

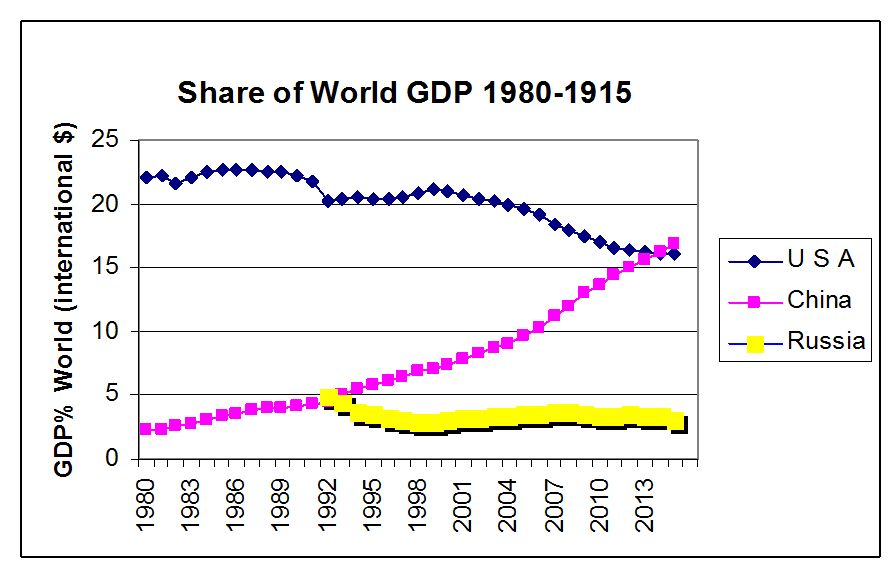

Will China be able to move into a higher level of economic development? Clearly China has extensively caught up with the Western hegemonic states. As shown by the figures below, by 2014 China’s GDP as a proportion of world GDP had surpassed that of the USA; and the USA had experienced a regular decline. Russia is shown for comparison.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base.

Purchasing power parity (Current international dollars).

While the chart shows the income of countries, the picture changes somewhat when we consider per capita income where China is well behind Western countries. When we take population into account, in 2015 the gross national income per capita measured by purchasing power parity in dollars, came to 13,345 for China, 23,286 for Russia and 53,245 for the USA (the highest was Norway with 67,614 international dollars per head). As far as its human development rank is concerned, China came in 90th place, well below Russia (49th) and the USA (10th). This index is an average of life expectancy, years of schooling and income. (http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf. Table 1. Accessed 20 Dec. 17)

Socialism brought considerable income equality to the USSR, and social-democracy in the European states followed somewhat behind. Currently, however, China’s Gini coefficient of income inequality is slightly higher those of the USA and Russia; and very much higher than the coefficients of the European social-democratic states. The figures for the period 2010-2015 are - China: 42.2, Russia: 41.6, USA 41.1 and Norway 25.9. (UNDP Table 3). (The higher the figure, the greater the inequality). China’s inequality has been on the rise since the introduction of economic reforms.

Clearly socialism can mean many different things. Chinese policy will address the problem of its undeveloped areas and no doubt will reduce the level of poverty. However, the rise of a very rich class of people in business and administration will provide a considerable challenge. Opposing ‘corruption’ will address administrative misbehaviour but will not confront rewards predicated on market performance.

The Challenge of Intensive Economic Development

Other challenges arise in the economic sphere. China’s growth was initially based on a mass production low wage economy. Innovation is now stressed as the essential condition for further catching up with, and even surpassing, the West. Here China has had some success with the introduction of high level technology.

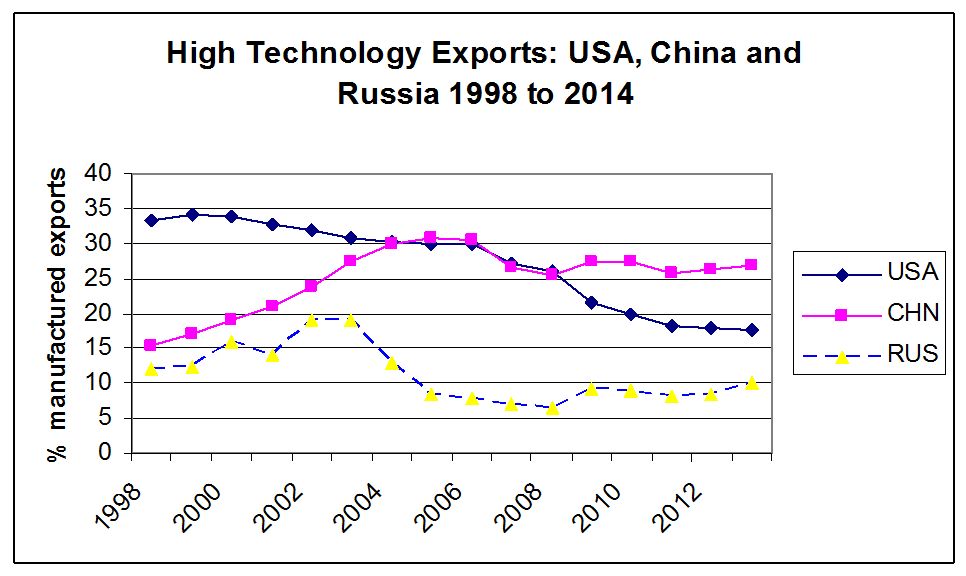

High technology exports as per cent of manufactured exports (World Bank data base, 2015).

The export of value added manufactures is an index of economic dynamism. The United States has experienced a steady decline in its share of high technology products in its manufactured exports. As we note from the figure above, US exports of high technology products (as a proportion of all manufactured exports) declined from 2000 in the face of the rise of Chinese high tech manufactured exports. Since the world financial crisis of 2007-, China has increased its share of high tech exports and that of the USA has fallen. However, one must be cautious in interpreting these data. Many hi-tech exports from China are the products of foreign companies located there, and innovation and new product development are a different story. China can certainly make high quality products which previously were made in Europe and the USA. Whether China can invent its own high tech products remains to be seen.

The ‘New Era’ in Chinese policy will entail a stronger presence in international affairs and the rise of a regional political bloc encompassing countries presently members of the Shanghai Cooperation Agreement and the BRICS. The One Belt One Road initiative is symbolic of this development. China may also turn to the United Nations, where it is likely to find political support for its political leadership. While the old regionalism organised around NAFTA and the European Union is weakening and state sovereignty is being revived, China is likely to emerge as a leader of a political region centred on the Pacific. In pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the USA has strengthened the hand of China in the competing trading bloc of the Regional Comprehensive Trade Partnership (RCTP).

The Challenge of China’s Regional Leadership

The problem facing world politics, if this analysis is correct, is whether the existing hegemon, the USA, will recognise the considerable political and economic power that China now possesses and concede to China its right to regional leadership in the Pacific. Given the commitment of the USA to the region, such a course is fraught with difficulties. To achieve a peaceful transition, the USA could follow a similar course to Great Britain’s fall from imperial power and gracefully acknowledge China’s presence and claims. It could resolve to limit its direct influence to a line drawn at Hawaii. However, Donald Trump’s somewhat bellicose behaviour and his policy of putting ‘America First’ has lead him to put ‘the US military first’, thus making a political transition in the Pacific a potential cause of war.

Read also: The Changing World Order in 2017: The Rise of Populism

David Lane is Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. He is author of The Capitalist Transformation of State Socialism.