2022: Global Markets at Risk?

© AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon

As the world emerges painfully from the Covid-19 pandemic, new worries appear to dominate global markets. Still, the rapid spread of the Omicron variant has led to renewed mobility restrictions in many countries and generated increased labour shortages. The global pandemic is not behind us, even if the worst fears about the latest variant have not been vindicated.

These new worries are diverse. Some of them are the heirs of the pandemic and of the ways different economies have faced the health challenge. This is the case regarding the considerable rise in debt (both sovereign and corporate) as well as inflation. Some of them have no direct links to the consequences of the pandemic. They have been generated by geopolitical conflicts and tensions, which were already quite in the limelight before the pandemic, but are appearing now, in the post-pandemic context, with a renewed relevance.

These worries are not clearly delineated; they could and probably will interact with one another.

A rocky post-Covid-19 economic surge

The first thing to understand is that the bright situation on the global financial markets is no more than a direct consequence of management by central banks of pandemic-related risks.

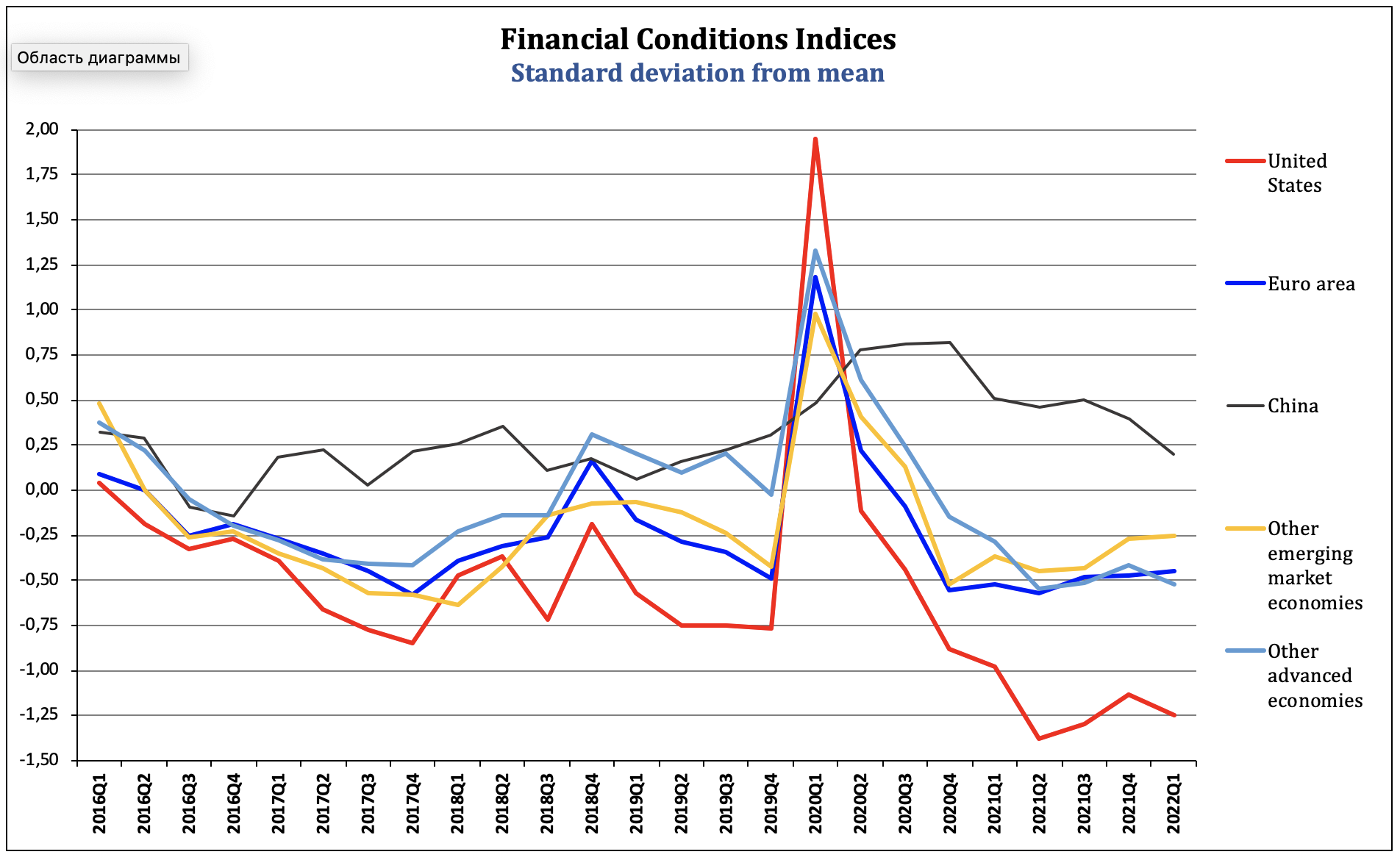

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, January 2022 Update.

All positions over 0.0 imply a tightening; all positions under 0.0 a loosening.

Even if there are some differences in the way each Central Bank has reacted to the situation generated by the spread of Covid-19 and the economic consequences of non-pharmaceutical measures taken to contain the pandemic (lockdowns and growing restrictions on internal and international travel), the current context is dominated by the huge amount of liquidity injected by central banks. While such injections probably saved the global economy in 2020, their consequences are now being felt.

There is, however, one major central bank that didn’t undertake a loosening of general policies: the Chinese Central Bank. This difference could be significant, as the Chinese Central Bank is now acting in reverse to the global tightening trend.

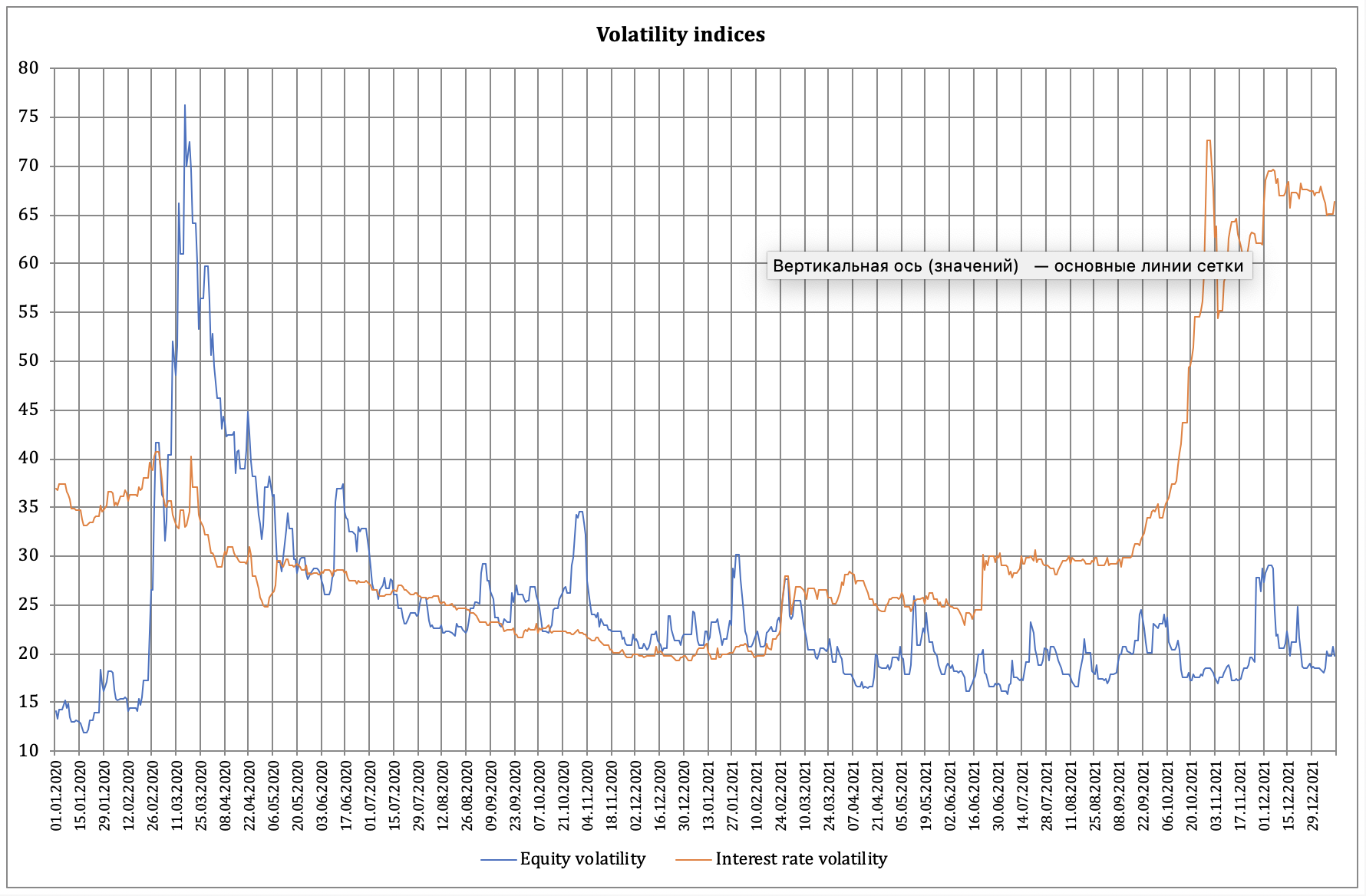

The rest of Central Banks are now on their way towards reversing their policies; this is a fact in Canada and Singapore, and something which will happen in the near future in the USA, where the FED meeting of next March could announce both a tightening of credit conditions and an interest rate rise. It may also happen in the not-too-distant future in Europe; financial markets all over the world are as high as a kite with all the previous liquidity injections. Quite interestingly, the volatility index for equities reduced considerably during the Covid-19 crisis, but the interest rate volatility index increased considerably since October 2021 when news of a future tapering began to percolate.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, January 2022 Update.

Geopolitical risks strike back

However, they could be quite surprised when they face the geopolitical tensions they had forgotten about during the pandemic. The biggest risks for markets in 2022, according to some 700 respondents to a Markets Live Global Survey conducted by Bloomberg, were inflation, the coronavirus, and geopolitical tensions. More than 30% cited inflation as among their biggest worries. Respondents often tied the risks of higher inflation to central banks either falling behind the curve, or tightening too quickly. Over a quarter were concerned about the coronavirus, with almost half of those focused on a new variant. The more detailed responses cited governments imposing new restrictions or central banks adjusting their policy in response.

About 23% cited geopolitical tensions, and 16% specifically used the terms war, invasion or conflict. This shows the global market’s sensitivity to geopolitical risks. The main examples given were raising tensions between China and Taiwan, and between Russia and Ukraine, particularly the possibility of an invasion. Any escalation in either case was seen as leading to greater conflict involving more countries. When it comes to China, respondents actually saw both geopolitical and domestic risks. Contagion linked to China’s economic situation was frequently cited, with the potential for slower growth and an impact on the housing market.

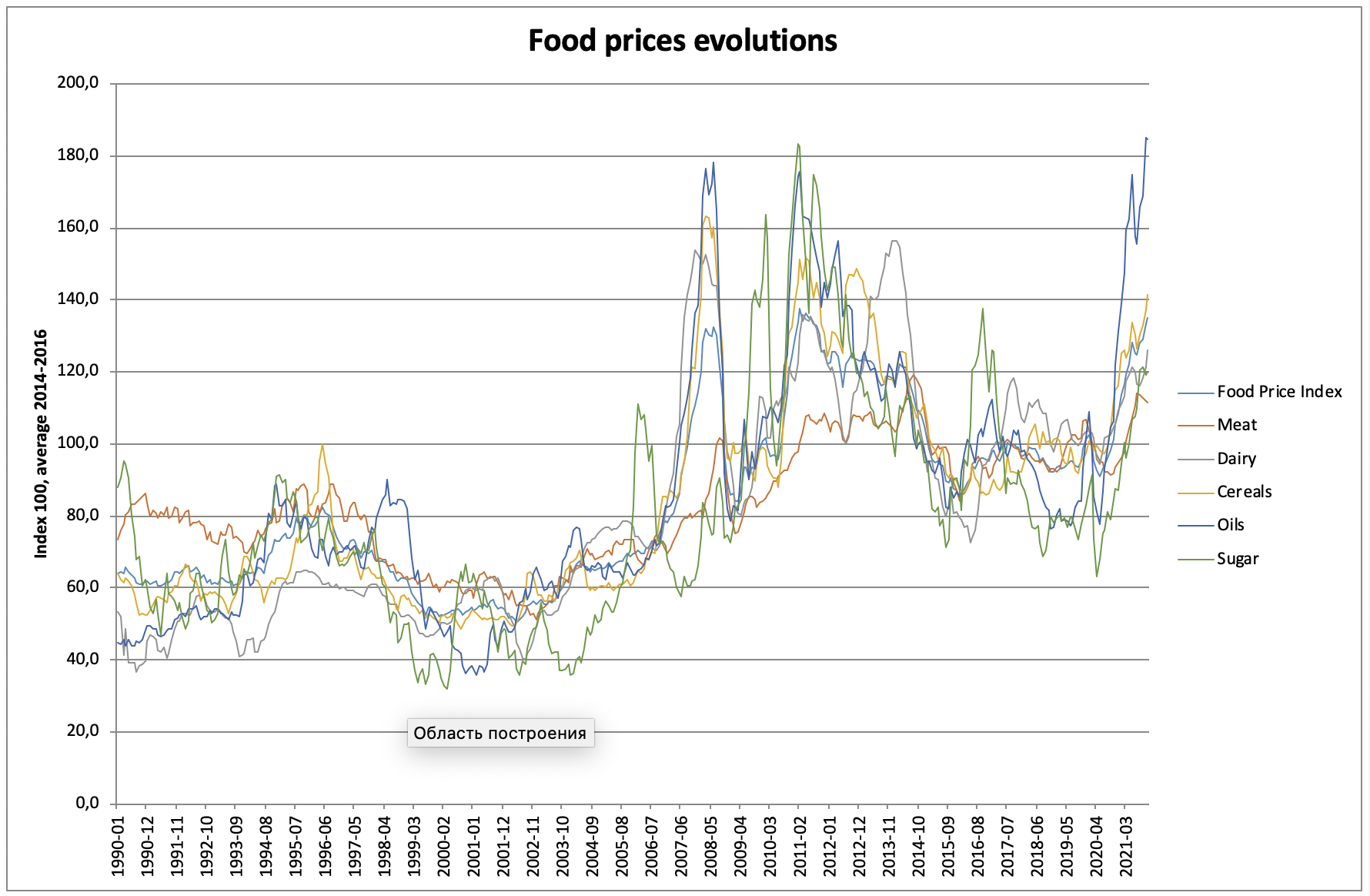

Source: FAO database

It may be said that these tensions aren’t new. USA (and its NATO allies) are engaged in two separate stand-offs, one with China over the South China Sea and Taiwan, and the other with Russia over Ukraine. These tensions have evolved with time but have always been considered quite important. The standoff with China has lost some of its media appeal, a fact probably linked to the Beijing Winter Olympics, which are taking place from February 4-20. Attention then focused on Ukraine, highlighted by Russian demands regarding its own safety.

The consequences of the NATO-Russia standoff have already been felt. Increasing tensions between Russia, the US, and NATO over Ukraine caused heavy selling in global stock markets on Tuesday, January 18th. Despite the rising oil prices, which reached over 88 USD a barrel (Brent Index) the RTS index in Russia closed on Wednesday January 19th 7.3% lower, at 1,367.5 points, after hitting its lowest level since December 2020 with 1,355.25 points. The losses in the Russian stocks spread to the global stock markets; especially to the emerging ones. Quite clearly, any move leading us closer to a shooting war could send global markets spiralling down, whatever possible Central Bank actions were to be taken. However, it is also significant that investors had refocused on inflation figures from the UK and Germany by January 20th. This reveals that the sensitivity to geopolitical risks is also closely interlinked with “pure” economic ones: inflation and the credit tightening.

War continues to exist and does not change as a phenomenon. And although the likelihood of a major war, one analogous to the global conflagrations of the twentieth century, is small due to their catastrophic nature and the deep interconnectedness of the modern world, regional and local conflicts continue to flourish, and the defence budgets of countries set new records from year to year, writes Valdai Club Programme Director Andrey Sushentsov.

Opinions

Geopolitical risks, the economic side

The 2022 forecast downgrade announced by the IMF in its latest Wold Economic Outlook (January 10, 2022) also reflects the high probability of serious revisions among a few large emerging markets, which are leading the post-Covid growth. In China, disruption in the housing sector, resulting from financial problems at several large companies like EVERGRANDE or FANTASIA, has served as a prelude to a broader slowdown. With a strict zero-COVID strategy leading to recurrent lockdowns at major logistic sites, mobility restrictions and deteriorating prospects for construction sector employment, supply to foreign countries and private consumption is likely to be lower than anticipated. In combination with lower investment in real estate, this means that the growth forecast for 2022 has been revised down in the current IMF World Economic Outlook survey relative to October 2021 by 0.8 percentage points, to 4.8%. This obviously has negative consequences for trade partners, and is poised to affect China’s current position as a locomotive of global growth.

But China is not alone in its predicament. Expected growth has also weakened in Brazil, where the fight against inflation has prompted a strong Central Bank monetary policy response, which will weigh on domestic demand. A similar dynamic is at work in Mexico, albeit to a lesser extent. Russia has so far escaped the problems that are plaguing other emerging economies.

Global growth was estimated at 5.9% in 2021. It is now expected to moderate to 4.4% in 2022, implying half a percentage point reduction when compared to last October’s forecast. The baseline scenario, which at this point makes no allowance for any serious “hot” geopolitical confrontations, incorporates the anticipated effects of commodities inflation, a shortage of several key products, mobility restrictions, border closures, and the health impacts of the spread of the Omicron variant. These vary by country depending on the susceptibility of the population, the severity of mobility restrictions, the expected impact of infections on labour supply, and the importance of contact-intensive sectors. These impediments are expected to weigh on growth in the first quarter of 2022. One can hope that the negative impact of these different factors would fade starting in the second quarter. But, if even an only “moderate” rise in geopolitical tensions and standoff is to lead to a renewed round of sanctions and counter-sanctions, this could cost at least another 1% loss in global growth and probably more.

The consequences of such a risk for global markets are probably twofold. First, of course, we would see a strong dip on financial markets, with all of the ‘classical’ consequences when it leads to major a rise in insolvency and bank failures. This would more probably than not force central banks to reverse or delay their tightening. Would it be enough to quiet the markets and prevent a too-sharp financial income effect? This is still yet to be proven.

We can also, however, expect a brutal international trade dip, induced by the sanction/counter-sanction mechanism exacerbating shortages and making commodities inflation even more painful that it is now. Distributional consequences on both producers and consumers are to be high in such a situation. Coming on to the tail of the Covid-19 crisis that has been described by Carmen Reinhart as “the last nail in the globalisation coffin”, that could well spell doom for highly globalisation-dependant advanced economies like Germany or the USA.

Events taking place in Latin America, be it the massive social movement in Chile or the victory of the Peronist candidate in the presidential election in Argentina, to which can be added riots in Bolivia are indicators of a important movement against what is called "neo-liberalism". These phenomena are not isolated. Similar movements have taken place in France, particularly the Yellow Vests movement, and others are taking place in Europe or the Middle East.

Opinions

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.