Russia’s Regional Options in the World System

© RIA Novosti

The Russian government will turn to strengthen the Eurasian Union as well as its political and economic alliances with the BRICS and the overlapping membership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

After the dismantling of state socialism, the post-socialist countries entered the world economy. This was a goal shared by modernizers in the Soviet Union and the socialist states of central and Eastern Europe who believed that joining the world economy would act as a stimulus to development. ‘Joining the world economy’ however involved significant changes not only in the internal politics of the socialist states to make them compatible to the capitalist world order but also in international alignments. The full implications of dismantling the structures of state socialism had not been seriously considered by those advocating radical reforms.Four major theoretical scenarios presented themselves. Firstly, a reformed socialist bloc keeping the existing institutions in place; secondly, the dissolution of the regional socialist associations (the Warsaw Pact and the CMEA-Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) and the participation of post-socialist countries as sovereign states in the world system as independent national actors; thirdly, the installation of post-socialist capitalist countries in the existing economic and political blocs of NATO and the European Union; and finally, the formation of a new economic region, possibly in association with rising capitalist countries then excluded from the hegemonic core, such as China and India.

The first path is predicated on the assumption that markets would develop both within and between members of the state socialist bloc under the reforms promised in Gorbachev’s perestroika proposals. The reforms provided assurances of movement to an open competitive market economy. In this context, the CMEA countries could have continued in a trading block based on the principles of the GATT/WTO. Such a scenario had some economic merit. The European socialist states had secured comprehensive economic and social development following the Second World War. They were capable of reform and development – moves to the market and a more pluralistic political system were intended.

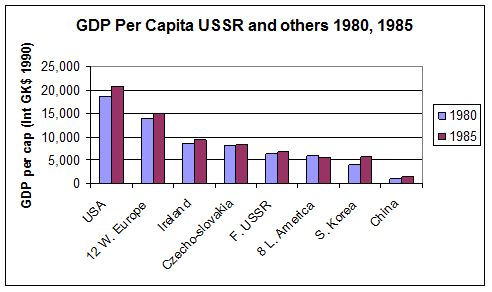

Figure 1 shows GDP per capital for different economies in 1980 and 1985 expressed in international GK dollars (1990 base) [1] .

The USSR in 1985 was certainly poorer than the average West European country, though it also included relatively undeveloped agrarian Republics in central Asia. What is of now of considerable interest is that the European socialist states were very much in advance of eight Latin American countries (average), South Korea and China which have made spectacular advances. With the hindsight of history, we now know that the economic advisers and political pundits who rejected adapting the path of the Chinese model of market development were mistaken.

Figure 1. USSR GDP in Comparative Perspective: 1980 and 1985.

Source: Maddison Project Data base. GK international dollars

The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm, 2013

Following the dismantling of the state socialist system, such within system reforms were not adopted. In the initial break-up of the socialist bloc, it was assumed that nation states are sovereign and act autonomously to promote their own interests. The transformation of the socialist states involved the privatisation of state assets concurrently with the assertion of national independence. Both of these developments led to strengthening the identity of the New Independent States and weakened any form of regionalism which would weaken their sovereignty. Initially, the post-socialist states of central Europe embarked on the promotion of a national form of capitalism and did not initiate a new economic or political bloc. They not only lacked a hegemonic regional power but also primarily sought to preserve their own political independence. Their moves to the Western market and the opening of their economies to Western investment occurred concurrently with the breaking of links between the socialist states which had involved a network of contracts and markets.

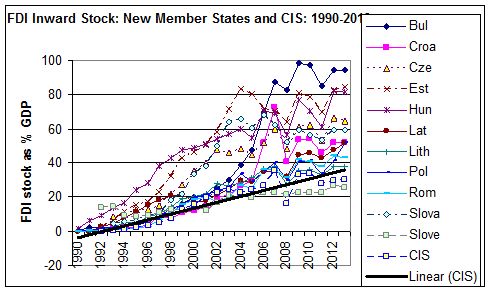

They became highly penetrated by foreign capital. Foreign investors were able to buy industrial and commercial assets in the former socialist states. The massive FDI in what have become the New Member States (NMS) compared to the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States between 1985 and 2014 is shown on Figure 2. FDI inflows to all the NMS (with the exception of Slovenia after 2006) are above the average trend line for the CIS states.

Figure 2. FDI Inward Stock: New Member States of the EU and CIS average 1990-2014 (% of GDP)

http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders

However, the post-socialist central European states were simply too weak economically and too small spatially to operate as effective economic entities when exposed to external markets. They had to form or join a region. In addition to cultural preferences, business interests undoubtedly pulled the New Independent States towards the European Union.

Moving to the European Union

The symbolic attraction of a return to their ‘European home’ would be a sharp break with the Russian-dominated Soviet past. ‘Europe’ provided a positive form of identity, economically rich and culturally civilized. There was also a dose of political realism in ‘a return to Europe’. After dismantling the Warsaw Pact and CMEA, the weaknesses of the post-socialist European independent states were exposed. The Central European post-socialist political and economic elites were fairly united in supporting a move towards integration with the EU. At best, the CEECs would achieve political and economic stability and a rising standard of income. At worst, it was better than staying out.

Moving to the EU, initiated by the reforming elites, required a reversal of national state-centered development. Such countries were required to adopt EUs norms and to become structurally compatible to the institutions of the European economic bloc. This was legitimated in terms of a ‘return to European values’. The European Union’s form of regionalism was not designed to support any state-led national development strategies. The thrust of the conditionality of the Acquis was to promote market competitiveness of the post-socialist states and to insert their economies into the world economy within the framework of a neo-liberal regional European bloc, epitomised by the unhampered movement of the factors of production (labour, capital, goods and services).

Meanwhile, the former republics of the Soviet Union (except the Baltic Republics) remained as independent nation states in the world system forming alliances in an ad hoc manner. While the Treaty of Rome provided that any European country could apply for membership of the European Economic Community, it became increasingly clear that Russia, for economic, political and cultural reasons, was not going to be considered.

Following the dismembering of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation’s major foreign alliance has revolved around the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) which was formed in December 1991. While many multilateral agreements have been concluded, the CIS lacked effective forms of enforcement and lapsed into a consultative forum between its members. Such forms of cooperation should not be lightly dismissed as they provided for collaboration on migration, security and the exchange of views on common problems between the participants political elites giving rise to a rudimentary type of socialization.

The difference between the central European countries headlong marriage with the regionalism of the European Union and the reluctance of the CIS countries to regionalize is due to the different weight of national and international interests in shaping policy. In the CIS states, there was a less fertile soil for foreign investment. Not only geography deterred foreign investment, but the political and economic elites were more domestic in character. They had been privileged by the privatisation process and were more nation-statist in orientation. Excluding the owners of large energy companies (which were concentrated in Russia and Kazakhstan), they lacked any push from international business to move the state towards a wider regional grouping. The export of materials required a free trade rather than a regional framework. The drivers of regionalism in the CIS were the state leaders who looked to a wider regional association for defence and security purposes in addition to the advantages of a larger market.

Unlike in the EU where the New Member States would be in an association led by (it was thought) benign foreigners, in the CIS the dominant power economically and politically was Russia. As the legitimacy of the new independent post-socialist states was predicated on independence from Russia, making a firm regional alliance ideologically and politically was much more difficult. An ideological legitimation which might have been provided by Eurasianism had few advocates in the Soviet Union, and was little known in the early transformation period [2]. The liberal outlook of the post-Soviet elites as well as the national basis of the new state regimes retarded the reformulation of a region based on the boundaries of the USSR. These factors hindered the formation of an effective regional organisation made up of states constituting the Commonwealth of Independent States. Ironically perhaps, it was much more difficult for Russia to lead and implement a new regional association for the CIS than for the European Commission to influence the new independent states of Central Europe.

The deficiency of the CIS in providing a basis for a positive geo-economic unit has led the Russian leadership to re-consider its wider economic and strategic alignments. There are three major strategic and geo-political ways forward: the creation of a Eurasian Economic Union; the enhancement of links with the European Union; and the formation of a transcontinental economic bloc, the BRICS (composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) involving a shift in geo-politics to the east. Striking a balance between these three options presents dilemmas to the Russian leadership.

Russia and the European Union

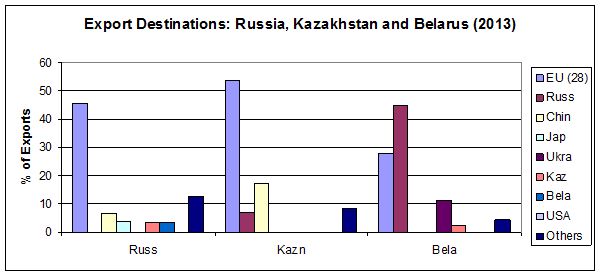

Russia’s strongest economic links are with the European Union. Russia’s trade both in origin and in destination is dominated by the European Union. As illustrated in Figure 3, only Belarus has a significant export trade with others (Ukraine). It is notable that even China is a minor recipient of EEU exports. Only Kazakhstan contributes some 18 per cent of its exports to China. Imports tell a similar story for Russia, which cannot be detailed here – the EU is by far the major supplier.

Figure 3 Eurasian Economic Union: Export Destinations of Goods and Services 2013.

Source; World Trade Organisation Data Base available at: http://wto.org/countryprofile/WSDBCountry. Accessed 1 October 2015.

President Putin, basing his argument on common membership of the WTO, has contended that both the EU and Eurasian Union are able to forge a wider pan European association.

While this has been widely ignored or dismissed, it does have some merit. It might be likened to the relationship of the European Free Trade Area with the European Union. Like the EU, the Eurasian Union is to be built on the laws of the market and global competition under the rules of the WTO.

The articulation of Russia’s policy to move closer to Europe is brought out in the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation 2013. ‘In its relations with the European Union, the main task for Russia as an integral and inseparable part of European civilization is to promote a common economic and humanitarian space from the Atlantic to the Pacific’.(paragraph 56). ‘Russia stands for signing a new Russia-EU framework agreement on strategic partnership based on the principles of equality and mutual benefit. …. A long-term objective in that area is to establish a common Russia-EU market’ (Paragraph 57).

These statements highlight a major dimension of policy of the Eurasian Economic Union with the EU. While a free-trade regime would continue, the countries of the Eurasian Economic Union would be shielded by its boundaries from more powerful forces in the European Union. From the viewpoint of the EU, such an agreement would further complimentary trade policies: the EU exporting manufactured goods and importing raw materials, especially fuel. In 2013 Russia was a major commercial partner of the EU: outside internal EU destinations, Russia is the fourth largest export market (6.8%) and the second largest import client (12.2%) [3] coming after China which has 17 per cent.

The synergy between the EEU and the EU, at least economically, is considerable. Greater economic integration would promote political integration enhancing conditions for peace, which is a major goal of the EU. Jozsef Borocz has suggested that the motivating force behind the EU’s enlargement has been to maintain its world ‘market share’ of GDP [4] . This being the case, the EU, if it pursues positively stronger links with the Eurasian Union, would secure a substantial market for its manufactured exports as well as a protected source of imports of raw materials. The wager on Ukraine, which had a negligible proportion of its trade and was a serious liability as an energy supply conduit, has been a costly economic blunder. It has led to political destabilization in Eastern Europe. EU policy, which is not our concern here, was unduly influenced by geo-political interests and especially by the concerns of the USA.

A partnership between the Eurasian Economic Union and the EU is perhaps a visionary scenario, as it would require the reversal of many current EU policies. The EU has rejected a closer agreement with Russia unless neo-liberal policy conditions and Western values are accepted. The EU would have to modify its current inclusionary policy to accommodate other regional interests with different values and institutional arrangements. This is not impossible. The EU has negotiated separate agreements with Turkey, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and even Singapore which promote favourable trade relations. Negotiations between the European Union and the USA over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership are another example of how cooperation is possible between two commercial blocs. Such negotiations include bilateral and multilateral agreements on tariffs and public procurement, cooperation on regulatory agreements and the enhancement of bilateral trade.

Despite the clear economic rationality of a EU-EEU linkage, the latter’s path to the world system based on neo-liberal economic principles has been effectively closed off by Western policies. The foreign policy stance of the USA, echoed by the EU to Russia particularly over Ukraine, may have been a tipping point for Russian foreign policy.

The Rise of Competing Geo-Political Blocs

In the absence of such a negotiated settlement bringing the EEU into closer alignment with the hegemonic core of the European Union, the alternative is the development of a competing geo-political bloc. Consequently, he Eurasian Economic Union is likely to evolve as a ‘counterpoint’, relying on greater state coordination and regulation economically under an autocratic political system. However, the EEU cannot be effective on its own; it is economically too weak to mount a very serious challenge to the European part of the hegemonic core. To build any significant alternative to the neo-liberal global order, it would need to combine with countries in other semi-core countries.

Since the Ukrainian conflict the Russian leadership has given more emphasis to linkages with the Asian-Pacific area and has strengthened ties to groupings such as the Shanghai Cooperative Organisation and the BRICS countries. A consequence of a short-sighted Western policy has been to push Russia to the East- economically and politically.

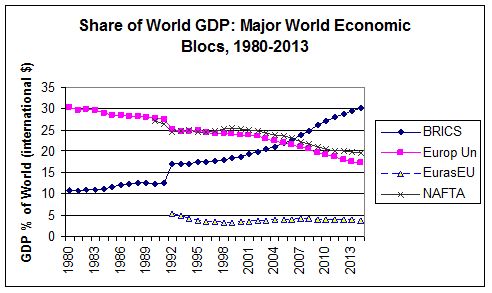

The decline in the world share of GDP for the USA and the phenomenal rise of China has led to the formation of four major economic groups which are shown on Figure 4. We note the unremitting economic decline of NAFTA and the EU against the rise of the BRICS countries. The export of value added manufactures is also an index of economic dynamism. The United States has also experienced a decline in its value added exports; its exports of high technology products (as a proportion of all manufactured exports) declined from 2000 in the face of the rise of Chinese manufactured exports. Figure 4 also illustrates that the Eurasian Union is a minor player with its share of global GDP being only 4 per cent [5].

Figure 4. Proportion of world GDP 1980-2014: BRICS, European Union, Eurasian Economic Union and NAFTA.Purchasing power parity (Current international dollars).

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Data Base, 2015.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015. Purchasing power parity (Current international dollars).

The aggressive trade sanctions towards Russia have had the effect of reinforcing the rise of a geo-political bloc based on the Eurasian Union and the BRICS, especially China. The geo-political consequences of Western policy push the members of the Eurasian Economic Union to the east. In 2007, under the BRICS was formed a Development Bank which is potentially an alternative to the IMF. At the 2015 Ufa summit, the EEU has (or will) set up free trade areas with Vietnam, Egypt, India, Israel, South Korea, Chile and South America. For countries in the semi-core of the world system, regionalism need not entail being absorbed into the hegemonic bloc of the G7 countries. China, Russia, India, Brazil and Venezuela and constituents of regional groups (Shanghai Cooperation Agreement, the Eurasian Economic Community, MERCOSUR, and ASEAN) can strengthen their position against hegemonic powers. The growing power of its economic base gives such countries political influence and military power. While not matching the armed forces of the USA, when combined these countries have considerable military resources.

Changes in World Geo-Political Power

The geo-political scene is changing. Rather than a unitary economic core around the USA, there is a growing diversity promoted by the EU, the EEU and the BRICS and a fragmentation of the dominant ‘core’ states which are divided by economic and political blocs. By 2007 the share of world GDP was greater for the BRICS countries than that of the EU or NAFTA, thus constituting a rising semi-core counterpoint. The statist character of China and Russia may restrain their own transnational companies from full integration into the world economy and concurrently the USA and EU may discriminate against their affiliates. Such formations have (or may develop) their own specific national or state capitalism (some having socialist characteristics). Whatever their economic complexion, they have different political and social identities to those of the hegemonic US-led core members.

However, within the ascendant semi-core are contradictory economic dynamics. A number of transnational corporations in countries like Russia and China favour neo-liberal policies which would facilitate their expansion and the repatriation of company profits (from which states also benefit somewhat). While China as well as the Eurasian states are less exposed to global capital and have a potential for internally led economic development, they also contain neo-liberal interests which derive from domestic companies seeking a status in Western markets as well as politicians and intellectuals driven by liberal ideology. Those at the bottom end of the labour market also would benefit from free mobility of labour. The possibility of the EEU becoming a ‘stepping-stone’ to the dominant core cannot be ruled out.

Russia is positioned between the EU and the rising power of China. Its short-term interest in terms of economic rationality lies in a stronger association with the European Union. This, however, has difficulties. Continuing the policy of comparative advantage will leave Russia as a major energy exporter to the disadvantage of manufacturing and value added industries. Moreover, the geo-political interests of the EU and NATO would seem to rule out a stronger economic and political association. The Russian government then will turn to strengthen the Eurasian Union as well as its political and economic alliances with the BRICS and the overlapping membership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Ironically, the economic policy of the Western countries will lead to import-substitution by the BRICS countries and will enhance their economic autonomy.

A more limited form of regional association including multinational agreements would be better suited to further development of the Eurasian states. The economic model of the European Free Trade Area (which preceded the EU) with limited political powers and other forms of cooperation, such as intergovernmental agreements and bi-lateral links with third parties, might be a more acceptable form of organisation. Other kinds of regional integration, cultural and social in form, could be pursued along the lines of the British Commonwealth. The Dominions remained as sovereign states and were subject to the policy of Commonwealth Preference which involved reciprocally-enacted tariffs and free trade agreements taking into account the different interests of the Dominions and colonies. As well as stimulating intra Commonwealth trade, it also shielded the UK from foreign competition. Such a regulated regional association would be able to develop an alternative value system to that of neo-liberal global capitalism, with a greater emphasis put on economic development of value-added industries as well as greater social security – the provision of employment, more equal distribution of income and wealth and the expansion of local and regional industries. These objectives cannot be achieved under a neo-liberal economic policy. Even Keynesian type policies cannot work in an environment with unhampered movement of capital, labour, goods and services.

One likely future scenario for the EEU is an enhanced form of regional economic organisation, along the lines of a strengthened Shanghai Cooperation Organisation which legitimates both international and national accumulation for their own national companies. The puzzle here for economic and political policy is to devise a regional bloc giving its members greater mobility of the factors of production while concurrently furthering a national developmental policy.

References

[1] Maddison Project Data base. GK international dollars. The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm, 2013 version. The Geary–Khamis dollar is a measure similar to purchasing power parity. In this source, the base used is the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar in 1990.

[2] Eurasianism was an ideology developed by Russian speaking people abroad and had little impact in the Soviet Union. See Mark Bassin, S. Glebov and M.Laruelle, Between Europe and Asia. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2015.

[3]IMF WEO data base, WEO 2015.

[4] Jozsef Borocs, Geopolitical scenarios for European integration, in F. Miszlivets and Jody Jensen (Eds), Reframing Europe’s future. Abingdon: Palgrave 2015 (pp.19-34), see pp.20-23.

[5] Based on IMF WEO data base accessed December 2015.

Views expressed are of individual Members and Contributors, rather than the Club's, unless explicitly stated otherwise.