On Tuesday, September 17th and Wednesday, September 18th, the REPO market in New York experienced a short but violent crisis. This crisis was a sign of the endemic fragility of the interbank markets, which in reality have never recovered from the financial crisis of 2008-2009. The regulatory authority responsible for the markets, the Federal Reserve of New York (FRoNY), had to stage a massive intervention, on the orders of the Federal Reserve, to restore calm and save the markets from a complete banking liquidity collapse; such a crash could have led to the bankruptcy of systemic banks within several days. This was a clear symptom of a situation where, without the action of central bankers, the system would be paralyzed. Did this crisis portend a forthcoming financial collapse? Probably not an immediate one, as central banks have learned to react quickly. But this crisis highlights the extreme fragility of the entire architecture of the international financial system, despite the strengthening of prudential measures that was undertaken immediately following the financial crisis of 2008.

The heart of the problem: the question of bank refinancing

The issue of bank refinancing is crucial for the smooth functioning of the economy. Without permanent refinancing, the banks would quickly run out of liquidity, and the credit would disappear. Yet banks are institutions that manage huge amounts of money. Why, then, do they need refinancing?

The essential reason stems from the delays in repaying the loans they agree to, against the deadlines relating to the loans they subscribe to. Banks have not been operating with their own funds for a long time. They borrow either from the public (these are the demand deposits of individuals and businesses) or from the financial markets. The latter loans are generally short-term, whereas the assets of the banks, in other words, the loans they have granted to individual borrowers, as well as to companies and to public entities, are long-term ones. This is called “transforming” short-term debt into long-term assets. They are therefore obliged to renew their loans regularly in order to maintain the equilibrium of their balance sheets. This question, it must be emphasised, has nothing to do with the solvency of the banks. A bank can be solvent (having a balance sheet in equilibrium) and be at a certain point in a situation where they lack liquidity; in other words, a bank’s immediately liquid assets are insufficient for it to make immediate repayments. If the banks were operating in isolation, or if they had to work without the support of the central banks or the interbank market, their credit activities would be far more limited than they are. That is why, since the nineteenth century, the principle that central banks are a “lender of last resort” has imposed itself. Governments have also sought to develop the interbank market, so that banks can cope with liquidity jolts (in France, it took, among other things, the introduction of the law of 1973). We understand the crucial importance of the bank liquidity market.

To manage situations where liquidity is excessive or lacking, banks can look to two Wall Street market institutions:

1. They can borrow from day to day from the central banking system, using as collateral some of their assets, such as treasury bills. This is the so-called overnight bank funding rate (OBFR) or overnight bank financing rate. This rate is a measure of overall, unsecured, day-to-day bank financing costs. It is calculated using federal fund transactions, certain transactions in euros and certain transactions in domestic deposits. The federal funds market includes unsecured domestic borrowing in US dollars by depository institutions from other deposit-taking institutions and certain other entities, mainly government-sponsored enterprises.

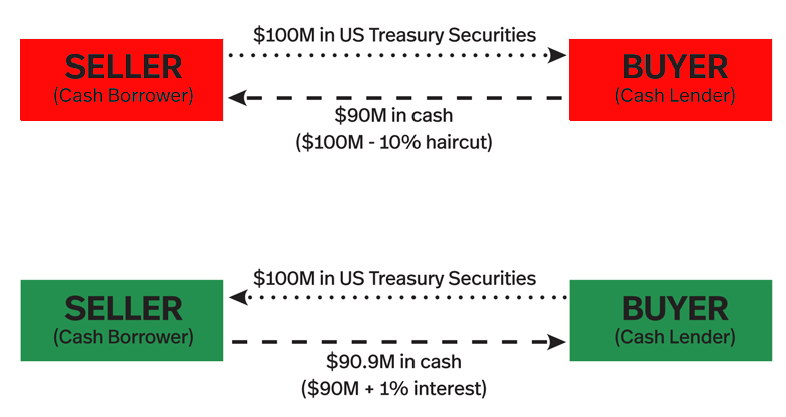

2. They can also use “REPO” financing. This is a secure instrument for banks, made available through bank-to-bank contracts. Relying on these has quickly become unavoidable. An institution sells assets – for example French or US government bonds or any other obligation – to another institution and undertakes to buy them back on a given date and at a price fixed in advance. It therefore obtains liquidity, less a “discount” of 10%, which corresponds to the insurance taken by the second institution. After 24 hours or more, according to the terms of the contract, the financial institution returns the money to the lender, plus a 1% interest rate, and in return recovers the securities. If it does not have the necessary funds to proceed with the repurchase at the end of the contract, the other institution remains the owner of the securities provided as collateral for the transaction and can resell them. In so-called tripartite “REPOs”, an “agent” intervenes between the banks and ensures that the value of the assets is sufficient to guarantee the amount that has been lent throughout the transaction. REPOs are therefore based on contracts between two legal entities (the banks). In New York, it is the Federal Reserve of New York (FRoNY) which keeps the accounts, day by day, of these contracts.

Figure 1

Description of operations on the REPO market

What is the REPO market

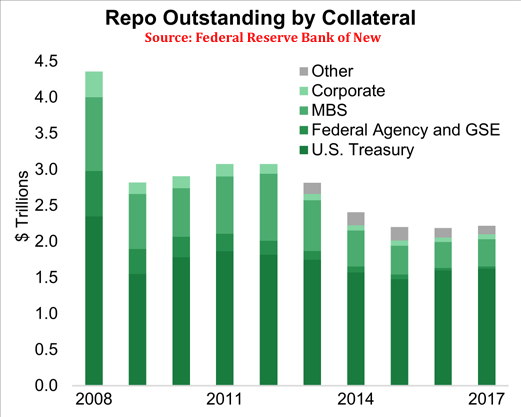

The REPO market is therefore a key element in the refinancing of financial institutions. With an annual volume of $2-4.5 trillion, we understand its importance. The fact that this market deals in high-quality debt instruments including US Treasury bonds, securities issued by federal agencies, state-owned enterprises, mortgage-backed securities as well as AAA-rated corporate bonds ensures – in theory – that it is safe, because of the collateralisation of borrowing. In addition to allowing financial institutions to obtain short-term liquidity, the REPO market also allows for the diversification of the assets held.

However, we can see that this market has never really recovered from the crisis of 2008. The amount of transactions was at the time about $ 4.5 trillion per year. It fell in 2016 and 2017 to around 2.5 trillion, a drop of 45%.

Figure 2

The crisis of September 17th and 18th that continued on Thursday, September 19 and Friday, September 20, has therefore occurred on the REPO market. It subsequently contaminated the “OBFR” market. Given the crucial importance of the REPO market, it has created a real shock for the financial markets and served as an important warning for financial institutions.

What happened then?

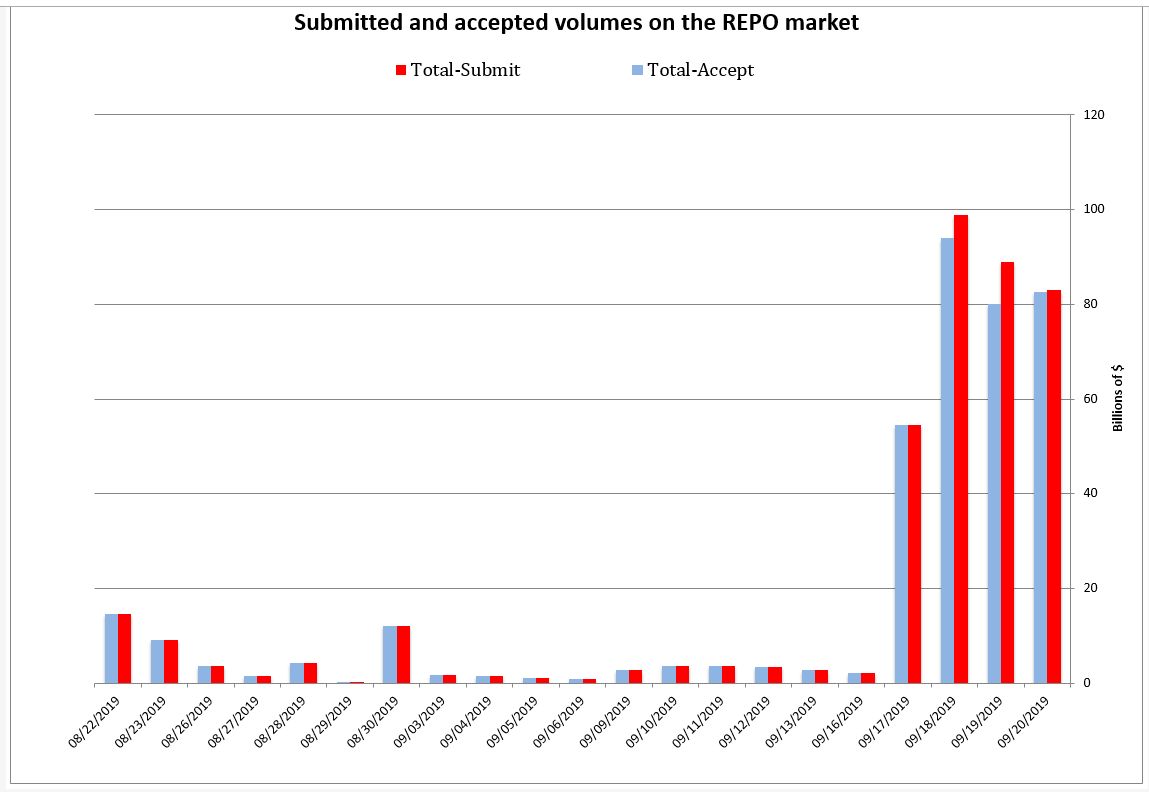

By Tuesday, the volumes requested (the “total submitted volume” in figure 3) exceeded the volumes usually accepted in the context of contracts between banks by a very large margin. The sudden importance of liquidity demand therefore spurred the rates of REPO transactions, which are normally between 1% and 2%. The latter then rose to nearly 10%, which is one of their highest historical rates, after having already climbed to 6% Monday. There was therefore a clear and immediate danger that banks would find themselves in a situation of illiquidity, that is to say, that they are unable to honour their obligations. However, this would have caused the bankruptcy of large banks, with all the consequences that one would imagine.

Chart 3

The September 17th to 20th Crisis

Source: FRoNY

The crisis came then from the huge increase in REPO needs. As can be seen in Chart 3, whereas in the days before, the needs were between $2 and 12 billion, it jumped on Tuesday to more than 55 billion and reached almost 100 billion on Wednesday. These volumes, if they had been maintained, would have involved $13-$25 trillion annually. It has been argued that these liquidity requirements came from the need for the banks to pay their taxes. This hypothesis, however, is very incomplete. The liquidity crisis in Saudi Arabia was added following the destruction of the pipeline through which about 50% of crude oil exports pass. It is also a possible explanation. But, these explanations show above all that only a minor “accident” is needed to completely disrupt the market. On Tuesday and the following days, the amounts requested (the need for liquidity) exceeded the amounts offered. The risk of a general liquidity crisis for banks was therefore very real.

The FRoNY, the Federal Reserve of New York, thus injected on Tuesday, September 17th , 53 billion dollars in the financial system and then 75 billion on Wednesday. It is this regional branch of the US Federal Reserve that manages market operations on Wall Street. It was therefore she who had to react, and react quickly, to stop a phenomenon whose consequences – a general blockage of the money market – could have been cataclysmic.

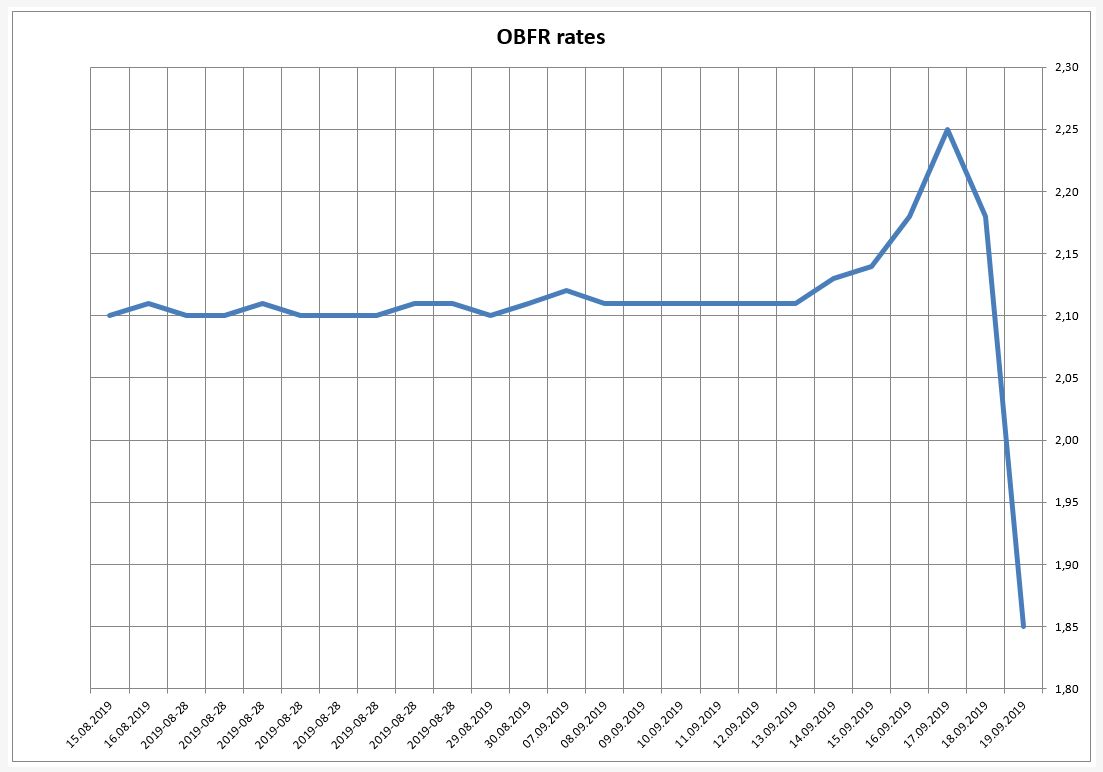

FRoNY’s intervention was also felt in the interest rates on day-to-day bank financing (OBFR). While the interest rate on OBFR operations had risen sharply, FRoNY’s intervention caused its immediate decline (Chart 4).

Chart 4

Source: FRoNY

The rate, in fact, was stable at 2.1%, it rose sharply to 2.25% on September 17th before falling again, because of the intervention of the FRoNY, to 1.85% on September 19th.

Harbinger of a crisis to come?

A liquidity crisis, let’s repeat, is the worst threat facing banks. Indeed, even if they are solvent, they can be swept away by a liquidity crisis within 2 or 3 days. We remember the spectacular bankruptcy of Bear Stearns in 2008, which occurred on March 17 and served as the warning shot before the subprime crisis and the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.

Analogies are tempting; they created the concern of specialists. But they are not necessarily justified, at least in the short term. The Central Banks activism, their capacity to put on the market huge volumes of liquidity, protects us – in the short term it should be repeated – of a new financial crisis. But, and this point is essential, the September events show that the markets cannot survive without almost daily action of these same central banks. In fact, there is no longer an interbank “market” because transactions would be impossible without the constant support of central banks. We are here back, without saying it, in the administered finance. This interbank market is the matrix of all other markets. Why did not it work on Tuesday and Wednesday, September 17th and 18th? In other words, why did the supply of liquidity not match demand? Several hypotheses are possible.

The first one is, of course, that the “credit” banks on the REPO market did not have the necessary liquidity. This was certainly true technically. But, as the crisis unwound, it’s true that they ended up finding this liquidity with the help of the central banking system. This would then refer to an assumption regarding the structural sub-liquidity of the REPO market. But then why?

This question leads us to the second hypothesis. Banks have little confidence in the securities they trade on this market. But they are – essentially – treasury bills. This lack of confidence in the products used to make the REPO market work may then reflect a general mistrust of the bonds and the fear that a “bond crash” will occur unexpectedly. It’s true that between specialists, talk of this was quite widespread...

Then a third hypothesis is possible. Banks that have liquidity want to keep it at all costs. This would explain, then, why a foreseeable “accident” (the payment of taxes in the United States) or unannounced (a request for liquidity from Saudi Arabia) could cause this jolt on the REPO market. The figure of $55 billion is, in fact, much higher than the amounts previously requested. We would then be in a situation where banks and financial companies seek to obtain “market liquidity” so as not to sell their own liquid assets. Such a situation would correspond to the “liquidity trap” of which Keynes speaks in his General Theory. The latent uncertainty in the market is so high that financial agents are very reluctant to divest themselves of the liquidity they hold. They prefer, then, to use different methods to obtain this liquidity, even if they accept an additional cost, rather than to touch the cash reserves they possess, if they have any.

These hypotheses can be said to contribute to a meta-hypothesis that could give full meaning to the September crisis. The uncertainty and mistrust inherited from the 2008-2009 crash have in fact never disappeared. Financial markets are constantly looking over their shoulder to see if a new crisis is not occurring. This concern and mistrust reflect the fact that financial activities, which have become increasingly disconnected from the “real” economy, are in reality less and less legitimate. The fact that the REPO market can no longer function autonomously thus says a lot about the state of the financial system in general, a system that has become completely dependent on the action of central banks. However, each time these central banks intervene to stabilise the situation, it ultimately only worsens anxiety and mistrust.

This, in turn, also raises the problem of the status of Central Banks. The need for their “independence” from government purview was originally theorized in the name of market efficiency and the fear of inflation. This “independence” was theoretically intended to ensure the effectiveness of central bank interventions. Now, markets have become dependent on central banks, as we have seen with the REPO market. However, this also applies to equity markets, just as the latter have (according to their balance sheets, which now contain a significant volume of securities) become dependent on market realities. The independence of the central banks prevents them from acting as an outside influence upon the markets, despite this being necessary for their activity. Beyond that, when institutions such as central banks have such an impact on economic activity and are so necessary for the day-to-day functioning of the economy, is it normal for them to be called “independent”? Shouldn’t they be directly integrated into government processes, and kept under the control of citizens?

The mini-crisis of Tuesday, September 17th is therefore a necessary reminder of the intrinsic fragility of the international financial system and the urgent need to reform it by giving States greater control over the instruments that make the markets work.