Discussions of the October Revolution, which have taken place in connection with its hundredth anniversary, have dwelt on the role of Lenin and the Communist Party in the seizure of political power, on the subsequent success of the USSR as a force for modernisation in the USSR and Asia, and its impact on the West. Authors have considered its notable achievements – its role in harnessing state resources for industrialisation and urbanisation, the inclusion of multi-ethnic populations in nation building, the demonstrative effect of the USSR’s military victory over Nazi Germany. And many have noted its failures – particularly the repression of the Stalin years and the stultifying effects of bureaucratic control.

Very few, however, have considered how or why the socialist countries led by the USSR (direct consequences of October) were dismantled in the late twentieth century. The epoch began by October 1917 was ended in the USSR with the deletion of the leading role of the Communist Party from the Constitution in March 1990. These changes were remarkable because the consequences of social revolutions, notably the French, English and American Revolutions, have been irreversible. The question arises of whether the October Revolution was basically flawed in its intended purpose of transcending capitalism.

Critics argue that, while October laid the foundations for state led industrialisation and the communist states and the provision of comprehensive public health, housing and educational facilities, the system of socialist planning inherently failed at the stage of consumer capitalism.

Economic Slow Down

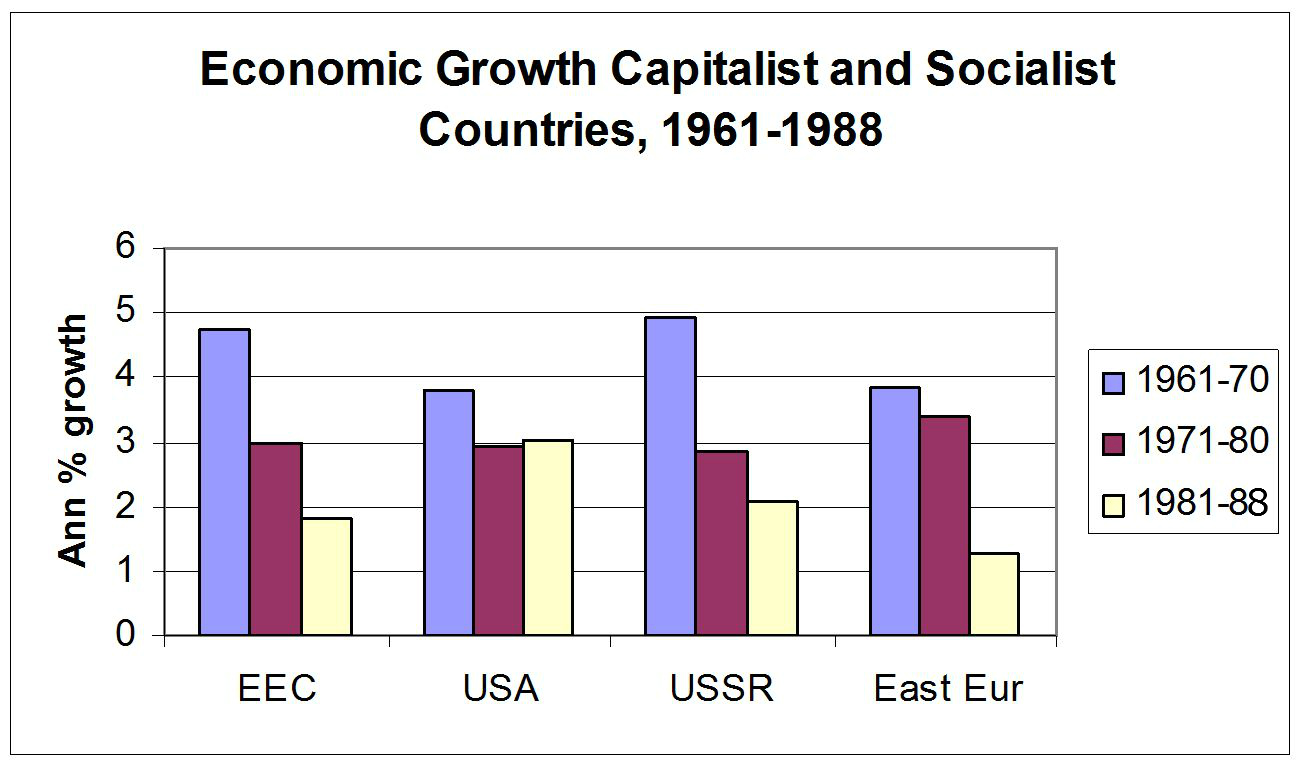

This failure of the system to fulfil the material and spiritual needs of the population is the major reason put forward for its ‘collapse’. This verdict is somewhat overstated. The economic slow-down in the European socialist states is only one side of the story. The USSR growth rates had fallen from 5 per cent (1961-1970) to 2 per cent (1981-88) and the socialist Eastern European countries experienced greater declines. Even here, however, growth rates were positive. As we note on Figure 1, the socialist countries were not unlike comparative capitalist ones. In the period 1980 to 1987, Western Germany had a growth rate of 1 per cent, the UK 1.3 per cent and France -0.5 per cent. But commentators do not consider that the European capitalist countries had suffered any economic ‘collapse’. China at this time had growth rates of 8.68 per cent and had maintained essential features of the socialist system.

Source: Economic Report of the President 1985-89. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office 1989.

When capitalist countries suffer economic crises (witness the economic depression of the 1930s, the financial crisis of 2007- ) reforms are made within the market system. In contrast, the institutions of the Soviet Union were torn apart by the Gorbachev reforms which demolished the command system as well as the legitimacy of central planning and Party leadership. Effectively the objectives of the October revolution were overturned.

Class Revolutions and the Transition to Capitalism

Both the French Revolution and the October Revolution at their inception were class revolutions. In both revolutions class rights played a crucial role – they were a catalyst, an impulse, for social change. Did class interests bring about the end of socialism in Russia?

Most commentators think this as somewhat unlikely as there were no obvious ‘antagonistic’ class forces in the socialist countries - the bourgeoisie had been destroyed in the processes of socialist construction. In my view, however, the development of the socialist societies led to a class structure with two major domestic elements which interacted with external elites to bring down the regime. First, an administrative and executive class and second, an ‘acquisition’ class.

The Administrative Class

The administrative class was composed of people occupying posts which gave control over the means of production, as well as over ideological, military and security institutions. Its members occupied positions of authority in the Party and trade union hierarchies as well as executive positions in government institutions (including economic enterprises, educational and health institutions, the media). The difference with market capitalism was that these positions did not allow their holders to inherit or to dispose of the assets under their control. Neither did the management of production enterprises benefit, as they would under free market conditions, from the surplus yielded from production of goods or services.

Members of the administrative stratum were in an ambiguous position. They occupied influential, secure and privileged positions in the ruling elites and many promoted communist the values. But they also had potential for an even more advantageous economic class position if they could turn their administrative control into ownership of property. From being members of a salaried administrative stratum or elite they could become part of a capitalist class with legal rights over the expropriation of surplus value and private property.

The Middle ‘Acquisition’ Class

The second class grouping was linked to the market. In the planned economy, employees were paid for their labour by a state enterprise or institution: the state had a monopoly of hiring, and determined wage rates and conditions. The exchange of labour power for money remained a feature of state socialism and income derived from employment was important in the determination of living standards. Under capitalism, market position mediated by sectional bargaining creates inequality between employees. Professions are able to utilise their bargaining position to secure excess payments – surgeons, showbiz professionals, and business managers.

Under state socialism the economic rewards were not determined by bargaining or sales through a market, but administratively. The difference between the actual level of rewards and the higher material benefits they believed the market would give them, created a disposition on the part of many professional and executive employees and skilled workers to favour the introduction of markets. Under state socialism there were extremely low differentials. This relative equality created a sense of dissatisfaction for many in the professional classes. Relative disadvantage predisposed some groups to advocate and to support policies of marketisation and later the privatisation of state property.

Many believed that relativities were insufficient to reward entrepreneurship and the acquisition of skills and provided arguments for a move to a market system which was considered to be ‘more just’ in rewarding skilled work. The liberal intelligentsia also resented administrative control over cultural expression, which weakened their professional standing, and over freedom of movement to travel abroad.

The Social Base of Counter-Revolution

Underlying the reform process were the interests of these two groups: sections of the state bureaucracy on the one hand and many middle class people (the ‘acquisition’ class) who believed that they would personally benefit if their life chances were determined by the marketability of their skills. Both could turn their social positions into class rights in two steps: first, by securing an economic market, and second, by acquiring rights to property. These social strata under state socialism formed a domestic ascendant class.

However, it is important to remember that they were not homogeneous social groups. In both these classes were loyal supporters and advocates of the socialist system. Support for the existing socialist order was particularly strong among the top levels of the state bureaucracy.

Initially, in formulating a reform process to invigorate the economy, Gorbachev sought a move to the market within the context of a Communist Party-led political order. To secure support for change, the leadership shifted the political balance through appointments and elections within the political elites from those favouring the traditional forms of administrative political control to younger people with a political affinity to the acquisition strata. Moreover, prompted by Western powers, Gorbachev created conditions which widened considerably the political opportunity structure, by accepting competitive elections.

However, to realise class interest requires political mobilisation. The political and security parameters of state socialism severely weakened the expression of competing political opinions and denied freedom to competing political movements. Consequently, there was insufficient political weight in the reform movement to articulate policies advocating an irrevocably move to a market system based on privatisation.

This may be illustrated from the practice of reforms enacted in Eastern Europe. In all the earlier reforms in countries, such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and the GDR, the state planning system and state ownership was not infringed. China’s domestic economic reforms maintained the hegemony of the Communist Party and preserved state ownership. The political leadership before Gorbachev had severely restricted the mobilisation of counter-revolutionary forces, and this situation continues in China.

In the early period of transformation under Gorbachev, many in the administrative and acquisition strata supported ‘the market’, but not a move to privatisation of state owned assets. In the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, in July 1990, voting on the ‘Silaev reforms’, which introduced a market in Russia, had the support of over 70 per cent of the government and Party elites, as well as of over 80 per cent of deputies who had a professional or executive background.

When one examines support for privatisation, however, government and Party elites were opposed. In December 1990, the vote on the introduction of private property was defeated, with nearly 70 per cent of what I have defined the ‘administrative’ class voting against it. On the other hand, of the professional strata (the ‘acquisition’ class), under 40 per cent voted against. It remained unlikely that the domestic administrative elites alone would have had the motivation to abolish their own political base to move to the uncertain system of capitalism. Also many believed in the superiority of the socialist system.

The Foreign Dimension

In addition to these two domestic classes were foreign interests acting through global political elites, which provided support and legitimation for a transition to markets and privatisation. This global dimension was crucial as a tipping mechanism which led to the articulation of class interests.

As a consequence of opposition to its policy, the Soviet leadership was pushed into dependence on outsiders to sustain the move to a capitalist economy. As Andrei Grachev, a former adviser to Gorbachev, has cogently put it:

'..[T]he task of [Gorbachev’s foreign policy] was not to protect the USSR from the outside threat and to assure the internal stability but almost the opposite: to use relations with the outside world as an additional instrument of internal change. He wished to transform the West into his ally in the political struggle against the conservative opposition he was facing at home because his real political front was there'.[1]

The politics of the radical reform leadership, first under Gorbachev and then under Eltsin, sought a pact with foreign world actors. As Raymond L. Garthoff pointed out at the time: Western policy moved from the ‘containment’ of communism to its ‘integration… into the international system’. The West, led by policy makers in the USA, was able to lay down the ground rules for such integration. They insisted on a policy of competitive markets in the polity (competing parties and competitive elections) as well as in the economy (privatised production for exchange, and money which would be negotiable in international markets). A transition would be assured by establishing the rule of law to guarantee rights to property and its proceeds.

These policies had clear implications for a transition to capitalism in the USSR and later in the Russian Federation. A marketised form of exchange paved the way for the induction of Western personnel, products and capital (to purchase domestic assets). The linkage with foreign interests provided the political ballast in the process of capitalist transition - in the place of an indigenous bourgeois class or, as in early capitalism, a landed aristocracy with a commercial outlook.

The interaction of these three political forces effectively ended the chapter of history heralded by October 1917 and led to an effective counter-revolution. In what remains of the state socialist system – China, Cuba, North Korea – the geo-political factor has been resisted and incipient forces for social change have been unable to articulate their class interests.

David Lane is Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. He is author of The Capitalist Transformation of State Socialism.

[1] Andrei Grachev, 'Russia in the World'. Paper Delivered at BNAAS Annual Conference, Cambridge 1995. p.3.