‘Brexit means Brexit’, thus Theresa May defined her position following the clear majority in favour of leaving the European Union in the referendum of 23 June 2016. She gave notice to leave the European Union (EU) on 29 March 2017 by invoking Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union. Prime Minister May is not only faced with resolving the UK’s settlement with the EU to the UK’s advantage, but she also is confronted with division in the British Isles which puts in jeopardy the historic union between England and Scotland.

Scotland’s Heritage

Scotland is an ancient kingdom, having its own language (Gaelic, though English is universal) with a chequered history of conflict with England. In 1707 a treaty between England and Scotland resulted in the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain, which was later (in 1801) joined by the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

While for most of the twentieth century Scotland was part of a unitary state ruled from London, under the Labour government’s Scotland Act of 1998, Scotland gained its own Parliament, with direct elections and devolved powers from the UK government. While Scotland has traditionally been a major socialist area electing an overwhelming majority of Labour Party members of Parliament, in 2015 this dramatically changed when the Scottish National Party (SNP) secured 56 out of 59 seats to the Westminster (UK) parliament. It captured Labour’s working class constituency which had been alienated by New Labour policies. Consequently, the SNP obliterated Labour’s traditional political base in Scotland. The SNP also became the largest Party in the Scottish Parliament.

The SNP is self-defined as a nationalist and social-democratic party. However, in 2014, the Party lost in a referendum called to declare independence for Scotland by receiving only 45 per cent of votes cast. Support for Scottish nationalism and claims for independence have grown since 2014, though current (April 2017) public opinion polls still show a majority opting for political union within the UK.

National Divisions of the Brexit Vote

This is the background to the historic vote for the UK to leave the EU. The SNP have been committed to remaining in the European Union as a member state. Unlike the Labour and Conservative parties, they opposed the holding of a referendum to leave the EU, and their members of parliament constituted the largest bloc among the 53 members who voted against (544 voted for) holding the referendum.

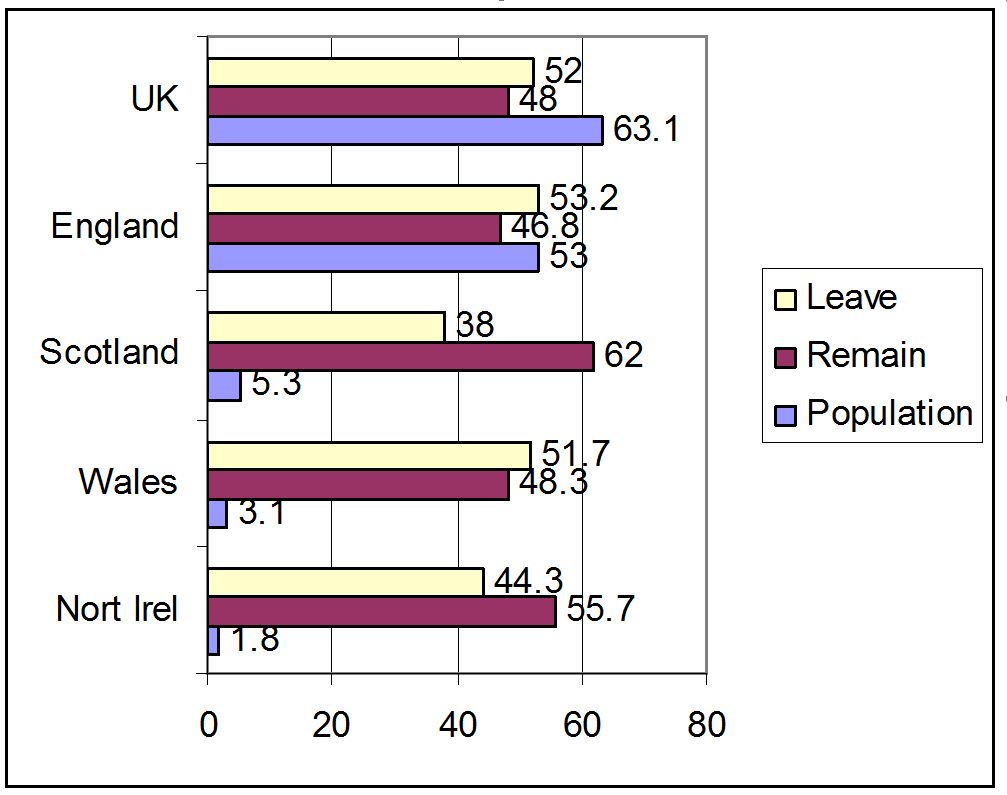

Against the expectations of the political classes, on 23 June 2016 the referendum returned an overall majority of voters to leave the EU. As shown in Figure 1, two of the national regions constituting the UK voted to remain in the EU, while England and Wales voted to leave. (Figure one shows firs the voting in per centages; leave, remain, followed by the population in millions). The much larger population of England secured an overall majority for leave of 52 per cent for the UK as a whole. While in England, every electoral area except London had a majority to leave, in Scotland all regions voted to remain – though there remains a large minority (38 per cent wishing to leave).

Figure 1 Results of EU Referendum by Country

Population (2011 census) millions. Voting: percent of votes cast

The leadership of the SNP was first to question the mandate of the UK result to Scotland. Its leader, Nicola Sturgeon, contended that the will of the Scottish people be recognised. If the UK government could not (or would not) negotiate a deal with the EU for Scotland to remain a member, then Scotland, she declared, would call a second referendum for its own independence. On 28 March 2017, the Scottish Parliament duly endorsed this sentiment by a majority of 10 voters. However, a referendum cannot be legally held without the agreement of the UK government; which will not be forthcoming until after the UK has left the European Union, scheduled for 2019.

An Independent Scotland in the EU?

The vision is opened up of an independent Scotland as a member state of the European Union coexisting with a sovereign England and Wales outside the EU. Would this be possible and what are the implications?

In its first Scottish independence referendum, opinion was that if Scotland seceded from the United Kingdom, it would lose its membership of the EU. This argument was advanced to deter further secessionist movements from the EU. Spain, fearful of the Catalonian independence movement, would veto the continued membership of a breakaway Scotland.

This argument has lost some of its power as Scotland, following the departure of the UK from the EU, would be an independent state outside the EU. It would be in the same position as other recent applicants – such as Slovenia or Latvia after the fall of communism, for example. Scotland as a former member is already adjusted to the laws and conventions of the EU and would easily be able to fulfil its conditions – unlike other intending members, such as Turkey.

However, the movement to Scottish independence concurrent with member state status in the EU presents many questions not only for Scotland and England but also for the European Union.

Firstly, as many of Scotland’s own Brexiteers complain, a ‘member-state’ of the European Union by definition loses much of its sovereignty to Brussels. For example, as a Customs’ Union, trade tariffs are an EU matter; the Common Fisheries Policy has opened up Scotland’s traditional fishing grounds to European competitors. These laws will remain – even for a Scotland independent of the UK.

Article 42 of the Lisbon Treaty also has a commitment to joint EU armed forces and the setting up of EU embassies which entails (eventually) a shift of sovereignty in foreign affairs to Brussels. The objective of the EU is ‘ever closer union’ which undermines the sovereignty of states.

While the UK has negotiated some special conditions from the EU, such as possession of its own currency, Scotland as a new member would be subject to obligations which would weaken its powers – such as the requirement (when possible) to join the Euro.

Secondly, there are important implications for European politics and its neighbours. One of the reasons for the setting up of the EU in the first place was the idea that such a federal unit would prevent war between the European powers. In the current EU, the United Kingdom provides an Anglo-American counter-weight to the continental powers.

In the absence of the UK, Germany’s economic power would embolden its leaders to enhance its political power. Consequently, Nicola Sturgeon’s view of England’s imperialist pretensions might well be replaced by those of the German Federal Republic. A scenario of a stronger German-led EU allied to Russia following the weakening or even break-up of NATO is one possible outcome of another Anglo-American led economic or political fiasco.

Thirdly, Scotland’s economic position has worsened since its first independence referendum. In 2014, oil revenues provided 7 per cent of Scottish gross domestic product. In 2016, it contributes only 0.1 per cent. Scotland is a net beneficiary of tax flows from England. Other countries of the UK (mainly England) are Scotland’s largest export market worth £49.8 billion, compared to the £12.3 billion (in 2015) absorbed by the 27 countries of the EU. Political independence might still be preferable, but there might be an additional economic price to pay.

Fourthly, Scotland in the EU and England out of the EU would require, under current EU laws, a hard border between the countries. This would also be required by England (to control migration) if freedom of movement of the factors of production between member states of the EU would continue. As part of the EU Customs’ Union, Scotland would be subject to EU tariffs on imports and exports to the rest of the UK. One possible solution would be for Scotland and England to be part of a free trade area with the EU but not part of the Customs’ Union.

Such a solution seems to be currently unacceptable to the EU and it has rejected similar proposals with respect to Ukraine. A more flexible economic and political policy on the part of the EU, however, might contribute to future cohesion.

A Compromise Solution: A Federal Britain

The government of Theresa May has indicated that it regards keeping the United Kingdom in a political union as a fundamental objective. To do so a political compromise with Scotland would have to meet the Scots’ claims for greater self-government. A federal United Kingdom would open up the possibilities of Scotland taking not only more powers from the UK government but also of regaining some of the authority now exercised by the EU. While this would make political and economic sense, it ignores the emotional appeal of Scottish ‘independence’ and the romantic attachment of many to the ‘European idea’. My conclusion is that Scotland cannot be truly independent in a federal United Kingdom, but neither can it as a member state of the European Union. Scotland within a federal United Kingdom outside the EU is an option worth consideration.

David Lane is an Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences (UK).